To celebrate the airing of the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction this Saturday, 4/29, we’re running a series of essays and feature analyzing and highlighting the implications of who was inducted in 2017.

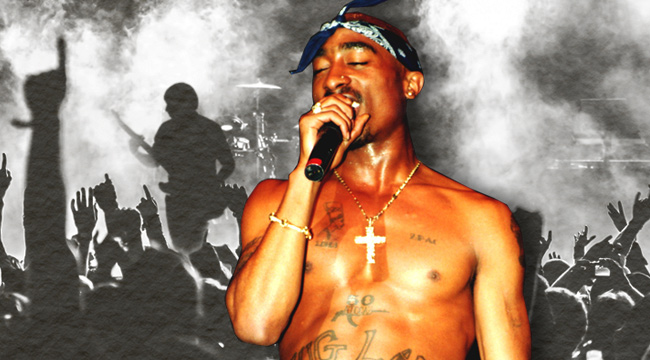

All jokes about T.I.’s questionable choice of Tupac-related wardrobe aside, it’s great that Tupac was finally inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. No, really it is. But Tupac didn’t — and doesn’t — need the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

There’s an argument to be made that rap and hip-hop music probably needs its own hall of fame. This ain’t that argument. There’s another line of thought that maybe the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame should do a better job of defining and nominating acts that fall under its purview. This ain’t that, either. Tupac absolutely deserved to be honored as an inductee to the Hall, especially with such precedents as N.W.A., Public Enemy, and the Beastie Boys filling out the remainder of the of rap’s delegation to its canon. However, like those other illustrious names, his legacy was sealed long before he even became eligible for nomination (2Pacalypse Now turned 25 last year). Despite the discrepancy of genre title, Tupac Shakur was and is hip-hop’s last real rockstar.

First off, check the stats: Over 75 million records sold worldwide, seven posthumous studio albums, a filmography including one of the most chillingly iconic villains ever to grace the silver screen (“I don’t give a f*ck about you, I don’t give a f*ck about Steel, and I don’t give a fuck about Raheem either. I don’t give a f*ck about myself!”), a documentary, and a biopic to be released later this year — Tupac is a household name for any of those reasons. To even have had a life that warrants a biopic is impressive by itself. Tupac managed to captivate the imagination of the listening public with classic rap tales like “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” then put that attention into a stranglehold with his Superior Court front-step antics and incisive, insightful interviews.

It was Tupac’s polarizing, public persona that showed the first telltale signs that he might be just as important to popular culture as Ozzy Osbourne or B.B. King. Like many of the hell-raising figures who’d come before him, ‘Pac’s brushes with the law were well-documented and numerous. Assault charges, jail time, and lawsuits followed him like groupies; an infamous late-night encounter with one led to a prison sentence for sexual abuse that nearly derailed his career — the same sort of charge that might have ended it in the present-day social and political landscape. He spat at camera crews (resulting in iconic images emblazoned on trendy fashion designs today), he flashed cash and guns in crowds, he rolled with a massive entourage of well-wishers and ne’er-do-wells including his own employer, Suge Knight. The only thing missing was an electric guitar.

Pac’s influence was indelible; even now, decades(!) after his death, young entertainers profess him as a source of inspiration. Kendrick Lamar, arguably the most important MC of the modern generation of rappers that came of age in the so-called “blog era,” not only cites Tupac as role model, idol, and example, but as an actual mentor, going so far as to stage an imaginary interview with his hero on “Mortal Man” from his Grammy Award-winning (for Best Rap Album) album To Pimp a Butterfly. Before Kendrick, Eminem, 50 Cent, Ja Rule, and DMX all borrowed elements from Tupac’s demeanor, his rap style, his fashion sense, his cavalier, “f*ck the world” attitude — with one big difference. Where many claimed to share Tupac’s “I don’t give a f*ck” ethos, it’s clear for a great many reasons, many of his acolytes do.

While Eminem suffered more than his share of civil cases, he was never accused of shooting a police officer in the buttocks. 50 Cent was shot four more times than Pac was, but it was long before the majority of the world had ever heard of the former drug dealer named Curtis Jackson, and though he built a huge portion of his mythology on the air of invincibility he derived from surviving his attack, he spent enough time in the hospital to scare Epic Records out of a potentially lucrative recording contract. Tupac checked himself out of medical care, against his physician’s orders, just three hours after the surgery that removed the bullets from his chest and head, and wheeled into court to face additional charges stemming from his prior arrest. After he served time, he re-entered the rap world with a vengeance, recording a volume of material that still serves as a motivational standard for rappers from Compton’s The Game, to Young Money millionaire Lil’ Wayne.

Whether you choose to believe that Shakur went out in a blaze of glory, or his self-destructive behavior and poor choice of acquaintances just caught up to him, there is no denying that his death in 1996 after a shooting on the Las Vegas strip shook the entertainment world to its foundations. The East Coast/West Coast enmity being stoked by rap publications like The Source and Vibe effectively ended with his and fellow rapper/sometime-rival Notorious B.I.G.’s deaths, and they left behind a void that hip-hop has been hesitant to fill ever since. Though he was cut down in his prime, he never had to face the built-in ticking clock that every entertainer granted their fifteen minutes of fame by fate eventually does; he was never mocked and ridiculed out of public favor like Ja Rule, never had to witness his vices slowly erode his talent like DMX, never dealt with wildly shifting pop cultural tastes like Eminem.

But he never got to age gracefully, either, growing into a wise, old-head uncle like Snoop Dogg (with whom he made “Two of Amerikkka’z Most Wanted”), or a rap elder statesman and mogul like Jay Z, a rapper whom he disparaged in song (“F*ck Friendz”), who was then disparaged by another rapper in a song sampling the first insult (“Ether”). Tupac was never afforded the opportunity to evolve into a respected actor like Will Smith, and we never got to hear what he’d think of Nas’ “Thugz Mansion,” which used a verse he recorded before his death (or of the aforementioned Jay Z diss, “Ether,” a battle-rap standard). This leaves him both a martyr and a monument, frozen in amber in a moment when he could have been anything but had already accomplished so much. Cut off in the midst of his upswing, Tupac never has to come down.

On April 7th, 2017, six hundred rock and roll experts cast their ballots and determined that Tupac was worthy of inclusion in a pantheon of performers that includes The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Police, Elvis Presley, Prince, and yes, Chuck Berry. Yet even if they had voted against his induction into the Hall, he had already been solidified as a true icon, no matter the genre. With or without the recognition of the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Tupac’s trademark bandana tied around his head, “Thug Life” tattooed across his belly, and even that goofy leather corset are all instantly recognizable and singularly tied to his image, to his words, to his music, and to his life — the life of the last true hip-hop rockstar.

Aaron Williams is an average guy from Compton. He’s a writer and editor for The Drew League and co-host of the Compton Beach podcast. Follow him here.