On April 21, 2016, Prince Rogers Nelson — adorned in a black hat, shirt, and pants — was found unresponsive in an elevator at his home and recording studio, Paisley Park. The cause of death was found to be an overdose of Fentanyl, an opioid 50 times stronger than heroin. Questions still abound. Did he get these drugs legally? Illegally? What kind of pain was he numbing?

Some information has trickled out. Prince had battled an addiction to Percocet decades before his death, with one family member stating that he’d started using the painkiller legally. On April 15, after a performance in Atlanta, Prince’s plane had to be grounded when the musician became unresponsive, the cause of which has been attributed to an overdose of pain medication. In the 24 hours before being found at Paisley Park, an addiction specialist, Dr. Howard Kornfeld, was called to come to the singer’s aid. Dr. Kornfeld wasn’t available, so he sent his son, Andrew Kornfeld in his place. It was Andrew Kornfeld who, along with two Prince associates, found the legend unconscious in an elevator. By that time, it was too late.

Opioids have been linked to almost half-a-million overdose deaths since 1999, with Prince being the most dramatic recent reminder of this epidemic. It’s a fact that 78 people die every day from an opioid overdose. Addiction to fentanyl mirrors other painkiller addictions: it starts with a prescription, then users increase their dosages and/or change their ingestion methods. Prince’s death offers us a harbinger of the rising fentanyl plague, which is inherently tied to the heroin epidemic.

To understand the dangers of fentanyl and fentanyl-laced heroin, we spoke to a DEA agent, two undercover narcotics officers (who spoke on the condition of anonymity), and one user. Their stories paint a picture of a dangerous substance that’s wrapping its claws around communities across the nation.

An Insidious Drug

“You are dealing with something that is incredibly hard to dose, and is potentially fatal at a microgram level. Not a milligram level. A microgram level.”

— DEA Special Agent Joe Moses

Fentanyl is a schedule two narcotic controlled substance, and is the most potent opiate available for medical or veterinary use. It’s an analgesic and an anesthetic, 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, and 30 to 50 times stronger than heroin.

“So, when you think about it, it’s just an incredibly potent opioid,” DEA Special Agent Joe Moses explains. “It’s incredibly dangerous, because it’s potentially lethal at very low levels. Ingestion of doses as small as .25 micrograms can be fatal.”

There are two kinds of fentanyl that reach the hands of users. There’s the clandestine variety, in which the precursor chemicals are used to manufacture the drug illegally. And then there is pharmaceutical fentanyl, which is medical grade pain medication used for people in the advanced stages of cancer. That fentanyl is very hard to get a hold of — only seen on the streets due to someone smuggling it out of a medical facility. Most of the fentanyl in circulation is of the clandestine variety, and it’s almost always mixed with heroin to increase the potency of the heroin.

“Fentanyl is just another cut — it’s a cutting agent that they use with the heroin,” says Undercover Officer Eric Smith (name changed), who works in Southern New Jersey. “It’s just another thing they can add to it that’s cheap and that brings the high up real fast. Sometimes the fentanyl can be too much, because these aren’t pharmacists mixing it up. When the mix isn’t right, that’s when people go down.”

In March of 2015, the DEA sent out a nationwide alert, specifying fentanyl as a dangerous threat to not only the user, but to law enforcement officials as well.

“Fentanyl itself — when conducting a search warrant or even a traffic stop — the police officers on the street may not even know what they’re handling,” Agent Moses says. “They may think it’s heroin. They may even think it’s cocaine. If it’s ingested or if it even gets on the skin, it’s a real cause for officer safety.”

That’s because fentanyl can absorb into the skin and can go airborne as well. If law enforcement comes across a domestic fentanyl laboratory, DEA’s clandestine laboratory enforcement team is called to the scene, where they employ breathing apparatuses and full body suits.

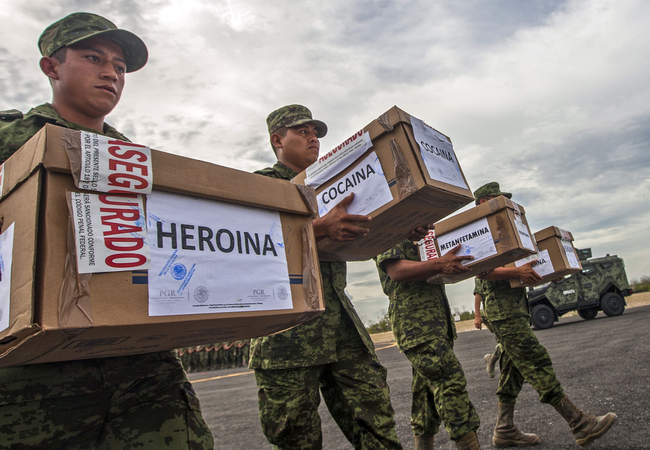

Seizures of these labs and of pure fentanyl caches have increased dramatically in recent years. According to the DEA’s Annual Threat Assessment Report, there were 618 fentanyl seizures in 2012. In 2014, the number rose to 4,585.

“It’s a huge concern for the DEA. It goes without saying,” notes Agent Moses.

In October of 2015, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) released an advisory on fentanyl-related overdose fatalities. Of chief concern were the 700 deaths attributed to the drug over a period spanning from late 2013 through 2014. That may seem like a relatively small number to trigger a major health panic, but the statistic comes with an asterisk: coroners don’t test for the drug unless they are specifically instructed to. So, in cases in which heroin is found in the system of a deceased user, medical examiners will stop testing for substances and will attribute the cause of death to heroin.

“Obviously, one concern is that fentanyl deaths may be underreported,” Agent Moses explains. “And again, given that fentanyl is often mixed with heroin, there could be an undetermined number of overdose deaths reported as heroin when in fact they’re possibly caused by fentanyl.”

Of the 4,585 fentanyl stashes that the DEA reported seizing in 2014, 10 states made up 80% of the haul — with Ohio, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania in the top three spots. Ohio’s 1,245 seizures almost doubles the amount in Massachusetts (630), making it ground zero for the drug. In 2014, Ohio recorded 514 fentanyl-related overdose deaths, dramatically outpacing the 92 they saw in 2013.

“They (Ohio) don’t get good heroin,” says Officer Smith. “They have to cut it with stuff. Here, [in New Jersey] we get high potency heroin.”

Outside of Ohio, most of the fentanyl-related overdoses seem to be concentrated along the Eastern seaboard — but confusion over the actual numbers is rampant. The undercover officers we spoke with are stationed in New Jersey, the fifth highest state on the reported fentanyl seizure list. Still, everyone seems distrustful of any statistics on the drug.

“Even if they did keep stats, there’s no one keeping track of it,” Officer Smith says. “You have to contact every coroner in the U.S. to determine what everyone’s individual toxicology was and whether or not it was related to fentanyl. And even if they did that, you would never even know if it was the fentanyl that killed them, or it was the heroin that killed them. You’re never going to get a true number, and even if you tried to, you’d be guessing.”

Furthermore, the undercover officers maintain that the DEA numbers come via surveys, many of which don’t get filled out by certain police districts. Compounding the issue is that there are no field-test kits for fentanyl available to law enforcement.

“You can probably quadruple that [death estimate],” Officer Smith says. “Seven-hundred deaths is probably just in [New Jersey’s] Camden County.”

This isn’t the first time the U.S. has seen a surge of fentanyl deaths. From 2005 to 2007, fentanyl-laced heroin had another dramatic upswing. Many of the deaths related to that outbreak were centralized in the northern part of the country, specifically Detroit. The rise in fentanyl during those two years were linked to a laboratory in Mexico. Compared to that outbreak, the “geographical dispersion” is much more expansive this time.

“This hasn’t slowed down,” says Undercover Officer Percy Jacobs (name changed).

“This doesn’t even compare (to the previous outbreak),” agrees Officer Smith. “When I tell you it’s non-stop, it’s non-stop. Your overdoses are pretty much all fentanyl based.”

With heroin use surging across the nation, and with more and more fentanyl hitting the streets, the toxic mix of the two substances is turning an already grim situation into an absolute nightmare.

Apocalypse Now

“It’s like the zombie apocalypse.”

— Undercover Officer Percy Jacobs

When fentanyl comes into the U.S., dealers and abusers rush to acquire the opioid. For dealers, it’s the chance to increase their profits by more than doubling the potency of their heroin.

“We did a job where we recovered pure fentanyl in a liquid form,” says Officer Jacobs. “What they do, they were taking the powder home and putting it in a blender — just any regular blender or coffee grinder — they were just dripping that in with the heroin, and they would mix it.”

For users, it’s a chance to get a better high. The danger is ever present, though, as the dealers who are mixing the fentanyl in with the heroin are usually not trained chemists, and just the slightest miscalculation in the mix might lead to what’s referred to as a “hot spot.” That “hot spot” is a pocket of fentanyl located in the heroin dose, and it carries fatal consequences.

“They get (the fentanyl), they think they know what they’re doing, they add a little too much, they bring it out to the street and they call it a ‘fire pack’ — everybody’s looking for it because it’s the best stuff out there,” explains officer Jacobs. “If it’s real heroin, they might be alright, but if it’s fentanyl making up the difference, that’s when they start dropping.”

“(My county) is going through Narcan like it’s water,” adds officer Smith.

Naloxone — commonly referred to as Narcan — is a medication that blocks cell receptors from absorbing opioids like heroin, and is used to reverse the effects of an overdose. The problem with fentanyl-laced heroin is that it’s so incredibly strong that law enforcement and EMTs have to sometimes administer up to four doses of the life-saving medication. Many counties have been using Narcan so often that they have to borrow it from neighboring areas in order to keep up with demand.

Still, despite the danger, the allure of the opioid is strong. Bobby, 35, is an addict who has struggled with various substances, listing his drugs of choice as methamphetamine and heroin.

“I don’t think there’s a drug that I haven’t used,” Bobby says. “Special K, coke — hard and soft — heroin, a variety of pills and opiates, Xanax, meth — pretty much everything.”

Bobby tells us that heroin purchased on the streets comes with various names like Pineapple Express, A+, Polar Bear, Nike (Just Do It), Icon, MegaDeath, and Poison — but rarely is it advertised that fentanyl is in the cut. Once people find out, though, the word spreads quickly.

“When you do [fentanyl-laced heroin],” Bobby explains, “it makes you feel even more euphoric and it would make me feel sleepy. You know, like that nodding out, but it happens from just one bag, not two or three throughout the day. When it’s got fentanyl in it, you’re like, ‘Holy shit. What the hell!’ And you find out later on, ‘Oh that’s what that was? That was wonderful!'”

Bobby’s story is similar to Prince’s and hundreds of thousands of other users who have “graduated” to harder substances. In his early 20s, he began dating someone who came across a stash of Percocet. His addiction started off with Percocet 10 mg., then he moved on to Oxycodone 80 mg. — back when it didn’t have a protective coating. After a brief attempt to beat his problem with Suboxone — a drug meant to stave off users from heroin and other high-potency opiates — Bobby was wrenched back into the throes of addiction.

“When I had started using again, it went straight to heroin,” he says. “It was a lot cheaper.”

“I don’t know of a single story where a person did not go through pills to get to heroin. Every single one,” says officer Jacobs. “Pharmaceuticals are making more people drug dealers now than ever before. You have more dealers, you have more users, and a majority of them make that jump right into heroin.”

With more pharmaceuticals flooding the streets, and prescribed medicine leading people toward heroin addiction, it’s all feeding into the fentanyl-laced heroin problem.

“In talking to people and being associated with that world, in the past year, [fentanyl] has been popping up a lot,” Bobby says. “And hearing people talk about it, it’s been around a lot more than it ever has been in the past. Yeah, it feels great — if you’re a user, that’s exactly what you want.”

If the DEA wants to stem the fentanyl fueled tide from feeding the heroin epidemic, they’ll have to do more than just set their focus on native soil.

Open Wounds

“I can say that it is on the rise… because it seems to be everywhere now. It’s everywhere.”

— Bobby (fentanyl laced-heroin user)

While there have been instances of domestic production of clandestine fentanyl, much of it is sourced from Mexico. Mexican cartels like the Sinaloa Cartel, New Generation Jalisco Cartel, Juarez Cartel, and Los Zetas help push the supply of manufactured fentanyl over the border. Mexico, just like domestic production labs, gets its precursor chemicals directly from China. The pipeline from China to Mexico to the U.S. is something that the DEA is trying to dismantle.

“I can tell you that we have a very robust dialogue with the Chinese authorities, and in general, the Chinese authorities have taken significant action on their synthetics,” explains Agent Moses. “For instance, they just made illegal over 100 synthetic compounds. Obviously, the United States is not the only country that has raised concerns with them.”

The DEA has been trying to “sound the alarm” on the flood of heroin and fentanyl swarming through high-risk drug zones for three to four years now, but the first time that public affairs began taking calls on the substance was when Philip Seymour Hoffman died in 2014. Prince is another high-profile name, but instead of fentanyl-laced heroin, it was strictly fentanyl that killed the entertainer. It’s a rare case, as fentanyl is hard to get a hold of in its pure form — especially since the singer and musician was not suffering from any illness that might require such a high potency pain medication. The mystery surrounding his death goes back to how he was able to procure the opioid. Which is a question across the board.

The DEA and other agencies want to stop the flow of fentanyl into the states, so they’ll have to bite the head off the snake, and that snake emanates from China.

“Supply? That’s a lot of work,” says Officer Jacobs. “It’s tough. DEA have certain units that deal with pharmaceuticals. You’re talking someone that can order it online from China and get the precursor chemicals — they’ll mail it out anywhere.”

When Agent Moses was asked about just how the DEA and other law enforcement agencies can stop the flow of precursor chemicals to Mexico and the U.S., the answer seemed boilerplate:

“DEA will continue to address the threat by doing what the public expects of us, which is targeting the top level of drug dealers, conducting enforcement of operations, protect the communities, and doing things like this which is putting the word out through media.”

Looking at users like Bobby helps to understand just how rampant demand is.

“Your whole life revolves around that,” he says. “Getting it, and finding money for it, ways to get it, and where to get it. You get sucked in. It becomes all about that, literally. Nothing else matters. Throughout the day, there’s not one point where anything does not — in one way or another — revolve around using it or getting it or finding money for it. It has definitely had an impact on my life. If I could go back and not do drugs for the first time, my life would have been a lot different.”

As long as heroin continues to surge through the streets, and fentanyl remains a readily available product to increase the potency of the drug, it’s hard to see an end in sight.