Is there a more intimidating discography for a neophyte to ponder than that of Frank Zappa? With about 110 albums to Zappa’s name, there are an ungodly number of entry points into his music. And no matter which album you pick, you will never find a truly “representative” Zappa LP. The best-known touchstones in his catalogue are practically islands onto themselves: The genre-hopping irreverence of Freak Out! and We’re Only In It For The Money, the metal-riffing jazz-rock of Hot Rats, the wise-ass AOR of Over-Nite Sensation and Apostrophe, the scatological satire of Joe’s Garage. Where in the world does one get started?

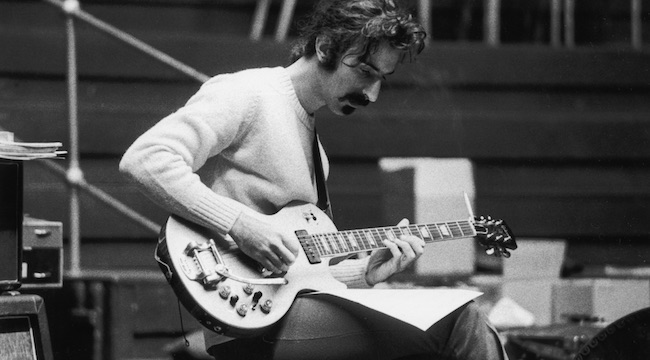

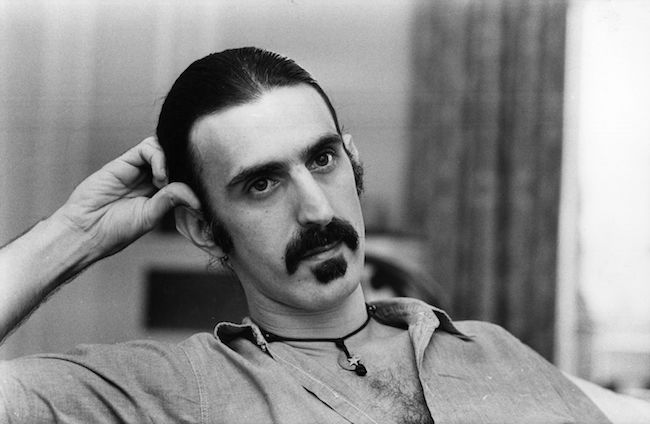

Brilliantly virtuosic, absurdly complex, painstakingly conceived, lyrically childish, restlessly creative, staunchly anti-commercial — Zappa can seem almost impossible to fathom from the outside looking in. On one hand, he was among the most original and technically gifted composers ever to work in the context of rock and roll, capable of writing both hooky jazz-pop ditties and sprawling avant-classical pieces without precedent in modern music. And then he would hire top-flight musicians to play those songs, rehearsing them tirelessly so that they could perform his music with spotless precision, even as he improvised spastic, chaotic guitar solos over the top of them for minutes on end.

But as high-minded as he was musically, Zappa could be downright piggish as a lyricist, relishing his very “’70s rock guy” attitudes about women and sex in scores of jokey songs that can come off now as straight-up misogyny or homophobia. In 1979’s “Bobby Brown,” one of Zappa’s most infamous songs, he details the sexual misadventures of a thoroughly unlikeable homosexual radio promotion man in decidedly un-PC language that is even more offensive now than it was 40 years ago. (Nevertheless, “Bobby Brown” was an international hit, reaching the top five in five countries, including Noway and Sweden, where it was a No. 1 smash.)

For detractors, Zappa is a vortex of obnoxiousness — musically obtuse and lyrically abhorrent. And yet, because of the sheer quantity of music he created, it’s possible to set aside what’s grating about Zappa and focus on his idiosyncratic talents as a composer, guitar player, and free-thinking all-American original.

All of those attributes, good and bad, are on display in Halloween 77, a new box set that commemorates a series of six blazing holiday shows that Zappa and his excellent band — which at the time included monster instrumentalists like guitarist Adrian Belew and drummer Terry Bozzio — performed at the Palladium in New York City in 1977.

Halloween shows were an annual tradition for Zappa, a monster-movie enthusiast who loved to incorporate the costumed freaks in the audience into his performances. On Halloween 77, the music is loose and spontaneous in spite of fairly static tracklists across the half-dozen concerts, with Zappa playing off the oddball crowd while leading his band through thrilling renditions of songs that would later appear on one of his most popular albums, 1979’s Sheik Yerbouti. The freewheeling, irreverent spirit carries over the packaging for Halloween 77 — the music is contained on a zip drive shaped like an “Oh Punky” candy bar inside of a plastic Frank Zappa mask and costume.

According to Ahmet Zappa — who, along with his sister Diva, runs the Zappa Family Trust charged with overseeing his father’s voluminous vault of unreleased music, films, photos, and various other documents — Halloween 77i s the first of what could be many releases commemorating the annual Halloween shows. “Unfortunately, the Halloween shows throughout the years, not all of them were recorded,” says archivist Joe Travers. “There’s a whole gap of mid-’70s shows that weren’t recorded, and it was most likely due to the union cost. But we do have material for a certain number of years to do future box sets.”

Incredibly, there will also apparently be future Frank Zappa concerts. In September, the Zappa family announced plans to mount two hologram-related projects, including a concert tour featuring former Zappa associates like Belew and guitarist Steve Vai, and a stage adaptation of Zappa’s iconic 1979 rock opera, Joe’s Garage. (Belew and another former Zappa guitarist, Denny Walley, have since backed out of the proposed Zappa hologram tour.) While both projects are still in the early planning stages, the idea of Frank Zappa returning to the road as a 3D image immediately sparked controversy in the niche-y world of Zappa fans. The most notable critic was Dweezil Zappa, who swiftly condemned his brother Ahmet and his associates, deepening a bitter family feud over the management of Frank’s legacy that’s been raging publicly since Gail Zappa, the Zappas’ matriarch, died in 2016.

Last week, I phoned Ahmet with the intention of discussing Halloween 77, but our conversation soon pivoted to the future of rock and roll hologram concerts, which aside from a recent European tour featuring the late Ronnie James Dio remain mostly theoretical. But considering both the strong health of the classic-rock concert market, and the frail mortality of the aging classic-rock musician population, hologram tours might very soon become commonplace. And if Ahmet gets his way, Frank Zappa could become a trailblazer in this arena, as forward-thinking in death as he was in life.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-’80s, Frank Zappa played special Halloween shows nearly every year. Why was the holiday special to him?

The freak scene. People put in all the time and energy to get dressed up and do outrageous things. [And] I think Frank also just loved science fiction and horror movies. He had a huge collection of horror movies that scared the hell out of me, but for him, I think, [they were] comical. I would sit with Frank and he’d be working on his music. He’d put headphones on my head, and I’d have an opportunity to watch monster movies with Frank in the studio. Frank was always working, so if I wanted to spend time with him, it was the best way to be in his presence.

Did the “freak scene” atmosphere influence the shows?

He loved audience participation. I think it evolved into becoming a tradition for him because of how the fans dressed up and how he could interact with them. From the story-telling standpoint, I think that Frank really enjoyed that.

Many of the songs that Zappa played during these shows appeared two years later on Sheik Yerbouti, including the “hit” “Bobby Brown,” which ranks among the most sexually lewd tracks in his discography. How well does a song about a “homo” who works in radio promotion translate almost 40 years later?

There was a toy store that we used to go to as kids. My dad loved ray guns or any kind of toys that made sounds. He would use them in his recordings. To protect the name of the real person that that song is, I think, based on… in hindsight, we were like, “Oh, that guy owned a toy store and that’s where I used to go all the time. That is pretty bizarre.” Frank was a very conversational person. He always was interested in people. He loved one-on-one conversations. I can just tell you that a lot of the stuff, songs that he’s written, it’s really based off of conversations with real people that really did weird sh*t.

But wasn’t there an element of willful provocation in a lot of Frank’s songs? It seems like he relished any opportunity to offend feminist or left-wing sensibilities.

I don’t know if that’s his reasons for doing it. I don’t think he just ever shied away from writing about real stuff or things that were, let’s say, a fringe element. I feel like everything is actually kind of tame. Maybe that’s the environment I grew up in, where I heard all this music. At the time, it was more like, ‘I can’t believe he’s saying that.’ But right now, I feel like he paved the way for people to be more expressive.

He would say, ‘There’s no word in the English language that could make you burn in hell. They’re just words. It’s the intention behind which you say them.’ And he was always contextualizing that for us as kids. If he was ever going after someone, it was to illuminate the fact that, in his opinion, they did something that was not hunky dory. But he was never someone that would just arbitrarily write a song that was trying to do something to hurt someone.

I have to ask about the hologram tour. Last month, the Zappa Family Trust announced controversial plans for a concert tour and a musical based on Joe’s Garage, both of which would feature a projected multi-dimensional image of Frank. For now, no dates have been set. Are you still moving forward?

I’m glad you asked! A hologram tour certainly lends itself to the kinds of things that I think would have made Frank really excited. In his book, The Real Frank Zappa Book, you read chapter 18, the failure chapter, he talks about wanting to take [hologram-style technology] public. At least when I talked to Frank about it, he was like, ‘I don’t have to go on a world tour. I can make content and have a world tour in one day.’ Or, ‘I could broadcast a giant experience, a holographic experience over the ocean.’ As a kid, you’re like, ‘What the f*ck are you even talking about? How is this even possible?’ And the cool thing is, we’ve actually just recently found his original business plans and documents. It was always something that Frank was interested in.

I always came from a standpoint of, ‘Okay, what’s really do-able out there? Who understands what we want to do in a Zappa capacity?’ This is a long-winded way of telling you the process that we’re in right now. Frank shot on a sound stage, in the early ’70s, this multi-camera shoot, where we have the multi-tracks of the audio, and that will be the basis of it. But if you think about just putting on a show, what does that actually entail? So you have the stage and the band and everything on the stage, and just from a purely organizational point of view, the new element is, okay, if you’re going to have some sort of super dynamic projection, you have to have a controlled environment, which is, let’s call it, for the sake of conversation, a hologram box. Just having the area where holographic projection can exist, the thing that’s super, fucking awesome about it, is anything can happen in that space. Any assets that are created can exist and appear to be real and accepted in that space.

I think I follow you. There seems to be some confusion over what a “Frank Zappa hologram tour” would look like.

I almost don’t like the word “hologram,” because I think that there’s tons of examples of the execution not living up to the notion of what a hologram can be. I think that part of the experience that we want to bring is all of the humor, the absurdity, and the visuals from across all the album covers. So it really is the bizarre world of Frank Zappa that’s being brought to life. It’s not just about having him appear to be back from the dead and on stage. That’s the kind of thing that you can get fatigued from. This whole show is a much bigger adventure than I think people realize in terms of the visual smorgasbord of awesomeness that will be hitting people’s eyes and ears sometime next year.

We’re just still in the very beginning stages of the organization and getting the assets ready. Because there’s certain things I think people will want to see — the improvisation [and] some never-before-heard music. We are trying to make those decisions, organizationally, about what musicians can play what on what nights. And if we have to make assets, it’ll have to relate to that musical moment.

Are you surprised that some people seem offended by the idea of a hologram Frank Zappa?

Am I surprised? No. I feel like it’s been pretty caustic out there with so much misinformation from my brother. It’s sad for me.

When I put together the Zappa Plays Zappa tour, way back in the day, and I approached my brother like, ‘Hey, do you want to go out and do this show?’ I remember the pushback. People were super angry at the fact that we might have video projections, so that Dweezil could play guitar solo with Frank. This is the thing that would bring people to tears! I think we can have an even more emotional experience in the sense that my brother could be side by side with Frank in a more tangible, real way, instead of having people look back and forth between a live guitar player and a giant projection of Frank.

I mean, we’re still doing projection. I don’t get the difference. We can now make it an even crazier, totally immersive experience. Like, how is it somehow bad? I don’t understand. The goal here is to have people experience Frank. How else are they gonna experience Frank on tour? No one wants to make something that’s stinky and bad. I care about every aspect of Frank. How do we do something that’s the most bizarre, super kick-ass Zappa experience of all time?

At this point it seems like this is the future, for Frank and all iconic musicians of his generation, given that there’s still a market for classic-rock concerts even though the classic-rock generation is starting to pass away.

Like, all of our heroes, all of the bands that I love, they’re gonna be gone. All of the people that played all this fantastic music, all going to be gone. And then, we’re gonna be stuck with [imitates techno beat] unce, unce, unce all f*cking day long. People have to do something to combat the unce.

Halloween ’77 is out now via Universal Music. Get it here.