Private prisons are nothing new for the United States, with some form of the practice dating back to the Revolutionary War. While these organizations have existed in the margins throughout U.S. history, it wasn’t until Reagan’s “War On Drugs” stiffened the penalties for non-violent drug users that lead to more people receiving heftier sentences for nonviolent crimes.

Over time, as the inmate population increased, federal facilities quickly became overcrowded, and by 1997 private prisons had started to become a much more prominent factor in our criminal justice system. Right now, there are 130 private facilities in the U.S., with a total of about 157,000 beds. Their occupants total about 12% of all federal inmates and about 6% of state inmates.

That’s a relatively small slice of the U.S. prison population, but private prisons have been coming under fire more and more in recent years as stories of abuse and neglect inside their walls have spread. This development calls into question their overall effectiveness in not only housing prisoners but in rehabilitating them as well.

In light of that, a question has to be asked: Can for-profit prisons exist as a necessary and functional part of our justice system, or will their focus on profit continue to marginalize inmates and trample their rights, ultimately causing these facilities to inflict more harm than good in the long run? While the answer seemed to be a firm “No,” a recent policy pivot by the Justice Department has pushed this all back into the discussion on how to properly house and rehabilitate America’s prisoners.

The Phase Out

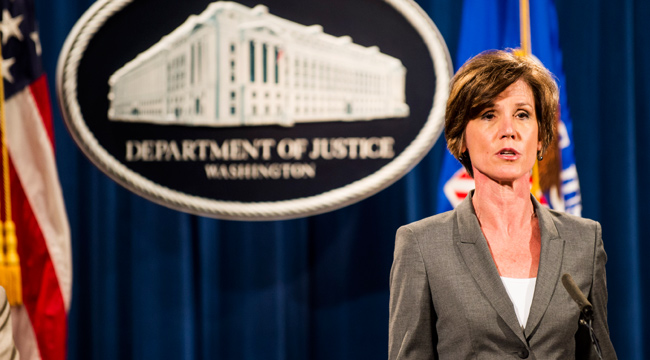

In August of 2016, future headline-maker Sally Yates, the Deputy Attorney General under President Obama, announced that the Justice Department would be slowly phasing out the use of private prisons. The decision was made after findings by the Office of the Inspector General (IOG), which concluded that instances of contraband, assault, and use of force were consistently higher in private prisons — which are all things one wants to avoid, particularly in regards to rehabilitation.

Oh, and they really weren’t saving the government all that much money, anyway. “They simply do not provide the same level of correctional services, programs, and resources,” Yates stated via the memo.

The announcement was seen as a good first step toward true criminal justice reform. And it was one that did not go unnoticed. Private prison stocks took a plunge after the news, with their only immediate comfort coming from the knowledge that this decision wouldn’t affect their iron-clad state contracts for some time.

Of course, for all the relief this gave to activists and those concerned with the state of treatment that inmates receive, everyone surely knew that a new administration could undo it all with the stroke of a pen.

The Abrupt Reversal

As Donald Trump’s administration started to take shape, newly-confirmed Attorney General Jeff Sessions sent out a memo to the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) in late February indicating that they would be rescinding Yates’ recommendation, stating that the decision “impaired the Bureau’s ability to meet the future needs of the federal correctional system.” A spokesperson for the BOP also told The Hill that the decision “will restore the BOP’s flexibility to manage the federal prison inmate population based on capacity needs.”

The reversal signaled that the new administration was far less concerned with the findings of the IOG, and statements made by both the GEO Group and Core Civic to The Daily Beast indicated that they felt the initial plan to be phased out of federal contracts was not only unfair, but it even undermined the services they provide.

Why the sudden reversal? Aside from an emerging trend of undoing all the policies put in place by the Obama administration, Trump is clearly keen on rounding up undocumented immigrants, half of which are held in private facilities when detained. Assuming these policies will continue, the need for private prisons is likely to increase significantly, at least in the short term.

The Problem With Private Prisons

So, why does this matter to you, a (hopefully) non-private prison bound reader? Well, there’s the worry that these facilities have the potential to be bastions for mistreatment and violent assaults while, at the same time, hindering rehabilitation and increasing the rate of recidivism.

In other words, people who are sentenced to prison often come out worse off than when they went in. And as bad as life behind bars is, violent assaults are three to four times more likely to occur in a private prison. What’s even more troubling is that these prisons aren’t subject to the same level of transparency that those run at the federal or state level are.

Granted, no one’s arguing that there shouldn’t be consequences for criminal action, but considering that roughly half of all inmates nationwide are non-violent offenders, subjecting them to potentially inhumane conditions is about the furthest thing from a ‘punishment fits the crime’ situation imaginable.

Sadly, it’s easy to think that reform is unnecessary when you filter the notion of criminal justice through a profit motive. These organizations make money (a lot of money) off of mass incarceration, and their lobbyists work hard to ensure that there will always be prisoners, which in turn guarantees a need for their services. Their contracts even go so far as to include occupancy requirements, meaning that these prisons have to remain at least 90% full at all times, regardless of the crime rate in and around their respective communities.

This lust for profit has even crept into the legal system, which has seen officials embroiled in “kids for cash” scandals, where they allegedly dole out unusually steep punishments to minors who commit petty misdemeanors in exchange for hefty kickbacks from these private institutions. If all this wasn’t bad enough, there’s also safety issues for their employees, who (generally speaking) tend to receive less training, make less money, and have a much higher prisoner-to-guard ratio.

Now, not everyone is convinced that these prisons are as bad as they’re made out to be. Author and legal scholar Sasha Volokh wrote in The Washington Post that the IOG report didn’t give a clear idea of the conditions in a private prison vs. those ran by the government. Volokh also suggested that a ‘mend it, don’t end it’ approach would’ve been better than phasing them out entirely. But to be clear, Volokh didn’t indicate that private prisons are any better in these manners than prisons ran on the state or federal level, just that the two are more-or-less indistinguishable.

Of course, with the new administration resuming the government’s reliance on these institutions, it remains to be seen whether there will be any internal reform or effort to “mend” their approach — though that seems unlikely. While the industry claims a more prominent success rate for their inmates, recent studies tend to contradict these claims.

Ideally, prison should function as a place where those who’ve been found guilty of crimes are punished, and with the exception of the most heinous offenders, are able to learn from their mistakes and eventually return to society better off than when they went in. Anything less is damaging to the inmates, risky for the employees, and ultimately an unnecessary burden on our criminal justice system and the communities that it aims to protect.