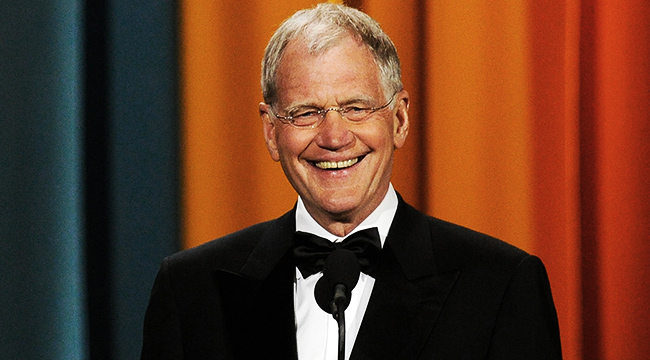

When David Letterman announced his plans to retire in early April 2014, two things immediately became apparent to New York Times comedy critic Jason Zinoman. The first and most obvious of these was the massive, Letterman-shaped hole he’d leave behind just over a year later in May 2015, when his last Late Show aired on CBS. With varying degrees of success, former Colbert Report host Stephen Colbert has done his best to fill in the gaps, but Letterman’s absence remains palpable.

As Zinoman told us in conversation about his new book out today, Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night, the second sudden realization concerned the project’s necessity. “I started working on it” in 2013 or 2014, he recalled, “but I ultimately gave up on it. I don’t think I was quite ready to write it, yet.” When news of Letterman’s impending retirement reached Zinoman while visiting a playground with his daughter, however, he knew then he was ready to write the book.

“Someone’s going to write this book,” Zinoman later told Letterman’s representatives, who ultimately agreed to an interview. The Times‘ writer’s emphasis on writing about the late night giant’s legacy, he suspects, appealed to the 69-year-old host’s love for his son Harry and helped win him over.

Please don’t take offense to this, but when I first read the book, it was much shorter than I assumed it would be. Letterman is a much more focused biography, as opposed to the larger, epic volumes often written about famous figures. Did you ever want to write that kind of book, or was it always going to be this focused?

There’s two answers to that. One is more about my taste, and the other is about the process. I’m not a huge fan of the giant doorstop tome biographies. I mean, obviously, I’ve read many great ones, but that is not my preferred style of writing. I’m a believer in the old saying, “You leave them wanting more.” Again, it’s purely personal taste. I’m a lifelong journalist who has written for tight word counts at magazines and newspapers, so it also just may be the background I come from.

The second point, which is a process point, is that the book did not start as a biography. It remains, to some degree, a book that tries to be a mix of reporting and criticism. It’s all supported by a central argument, which is that this period during the NBC years — primarily in the ’80s, but also in the early ’90s — is both the foundation of David Letterman’s reputation, and also one of the greatest comedic legacies of the modern era. That was my argument, aesthetically. That’s what I followed while reporting and writing this book. I want to figure out how it got to be there.

Then as I got into it, I realized that to write about David Letterman’s work, you can’t not write about his life. A talk show host is a very peculiar thing. He comes on stage, looks directly at the camera and talks in the voice of David Letterman. He’s not playing a character. He’s not an actor. His relationship to the audience very much has to do with what the audience knows about him, so I felt like I couldn’t write a book only about his work. I had to write about how his work intersects with his life.

As I got deeper into the book, I realized nobody else had written about him in this way. I thought there’d be other biographies on him already. Since nobody else was doing it, I felt I had to make the book bigger in scope. I would need to look at the CBS years and consider his retirement. It grew into the biography, but I think it still has the DNA of the original idea for the book, which was something else entirely.

In that sense, Letterman is more a biography of the shows than it is of the man himself. I found your approach quite helpful, too, as I was too young to fully appreciate his initial stint on Late Night. I grew up watching Dave on CBS which, as you point out in the book, was great for completely different reasons. It was very helpful to my understanding of Letterman.

It makes me really happy to hear you say that, because that’s one of the main reasons for the book. Unlike Saturday Night Live and Seinfeld — which are in a kind of steady syndication and easily accessible — Letterman’s work vanished as soon as it was broadcast. You have to work hard to find it, and even then it’s not always available in a systematic way. So the people who love Letterman, who are younger than me, don’t have the same sense of the difference between Letterman in 1984 versus Letterman in 1989. In the same way that a Simpsons fanatic knows the first year of the show is radically different from the third year, which is radically different from the tenth year. The same can be said of Seinfeld or SNL, for that matter.

To me, Letterman is just as important as those shows, and it has as many discrete aesthetic periods. If you listen to most people who talk about Letterman — including, again, fans my age and people who know him really well — they tend to talk about the differences between the NBC years and the CBS years. These points are very true, but I wanted to get more granular and really say, “These shows were radically different for a couple of years.” It’s kind of obvious when you compare it to other shows. This isn’t the same way that Seinfeld or something like that was different over the course of a certain period of time.

You often stress how private a person Letterman was, and is, throughout the book. That said, how did you get him to agree to let you interview him?

He didn’t for a long time. I’m not even sure how long, though it might have been a year and a half. I mean, he never said no. My pitch to his representatives was pretty much the same. I was 100% honest and said, “Look, someone’s going to write this book.” Someone wrote the Johnny Carson book, and it ended up being his former lawyer, Henry Bushkin. It was essentially an incredibly gossipy, and pretty unflattering portrait that emphasized Carson’s personal life while barely grappling with the work. So I explained to Letterman’s people, “That might be the book, or something like it, written by someone else. Either way, someone’s going to write this Letterman book, and here’s how I plan to do it. Here’s how I want to attack it, with the emphasis on the work.”

I made that pitch and he didn’t say no. Though he was actually quite helpful in terms of helping me track down other sources. Most importantly, whenever I interviewed other people, he didn’t tell them to ignore me. They went to him and said, “Should we talk to this guy?” I don’t think he said yes or no, but either way it was actually very generous of him. He could have shut down a lot of those interviews if he’d wanted to. So I went for a long time thinking this book would happen without Letterman’s interview, which I think motivated me to report like crazy. I went to Indiana and spent a lot of time with people who knew him during his time there, then I went to Los Angeles to talk to many of his former writers and production staffers. All of that work was really the heart of the book, as I see it.

By the time he agreed to it — and honestly, I don’t know why he agreed to it — I wasn’t on a fishing expedition. I knew exactly what I wanted to ask him, and it ended up being a great interview. He was direct, and I think it also helped that this was nine months after his retirement. He was no longer inundated with press coverage as he had been previously, and he’d been out of the limelight for a little while. I think he was in the mood to reflect a little bit than he already had publicly.

I assumed I could write this book without his interview, and I said that to myself for a year and a half. When you lie to yourself for a long period of time, it does things to your stomach. It eats away at your insides. I only realized the extent to which I was lying to myself after I finally interviewed him. As a result of that meeting, and my realization, I had to do a lot of serious rewriting. That’s what happened. If you want me to speculate, however, I’m happy to.

Please do.

He said to me after that he cared about his legacy, and he mentioned his son. Letterman really cares about being a great father, and I really think his son changed his life. I believed him when he said he cared about his legacy. This book is trying to make an argument for that legacy as being important, and he’s not the kind of the guy to toot his own horn in public, so my sense is that my planned approach meant something to him.

It makes complete sense that that would have a deciding factor on his agreeing to the interview. This brings up the book’s timeline, too. It’s evident you started working on this before he retired, but what first inspired you to write about Letterman’s career?

I had the idea for quite a long time. I’m not even sure when it exactly was, but it might have been 2013 or 2014. I started working on it, then stopped because I sort of decided I wasn’t going to do it. But it stayed in my head. I was covering comedy at the time, so it was always there. I’d already written one book at the time, so I knew that to really write a book, it takes a really long time. You have to be interested enough in a topic to live with this for many, many years. Also, it has to be a topic that enough people will care about. That’s how I ended up getting a book contract in the first place, because in the Venn diagram of those two things, the clear answer for me was Letterman. I felt this was a book that would clearly be of interest.

So I thought some more about it, but I ultimately gave up on it. I don’t think I was quite ready to write it, yet, though I know exactly when I changed my mind. It was when he announced his retirement. I was on the playground with my daughter, and my dad sent me a text about the news of Letterman’s retirement. Right then I knew I had to do it. I knew someone was going to do it if I didn’t, so I called my agent immediately and got back to work.

It’s always nice when things just fall into place for a project like this.

It’s true. This could have easily not happened at all. Look, I’ve done this before, and I know there’s nothing harder — at least for me — than finishing a book. There are some people who are really good at flying through book projects like this. But for me, it is a painful process to finish a book. It’s really, really hard. As a newspaper writer, I don’t have too much neurosis, but when it comes to a project of this length, it’s difficult for me, so I have to really be convinced of it. For this one, everything just added up.

Your subtitle, The Last Giant of Late Night, is sure to draw plenty of comment — supportive and otherwise. It makes sense, as Letterman’s heyday was marked by a small group of dominant networks, whereas the talk show field today is bombarded by cable, premium networks and streaming services.

Ten years from now it may look self-evidently wrong, but you put your finger on it completely. There’s the argument behind the subtitle, which took me a while to really go for. It’s twofold. The first aspect has to do with Letterman himself, and what a unique personality and performer he is. That’s what the book is all about. As for the second — which I mention in the book, though it’s not really a big part it — it concerns how the culture has changed. I think the culture has fragmented so much, it’s going to be hard to find somebody with the same impact as David Letterman.

People don’t realize how completely different the landscape was in 1982 when Late Night premiered. 12:30 at night in 1982 was much, much later than it is right now. Right now, at 12:30, you have a limitless number of options to choose from in terms of irreverent comedy. Not just on broadcast, but on cable and streaming and all kinds of other outlets. As well as live venues, which today applies just as much to people who live all over the country as it did solely to those in New York or Los Angeles in the ’80s. If you lived in one of those two cities back then, maybe you could go to a club at 12:30 in the morning. If you were like me and didn’t live in one of those places, however, you didn’t have those options. In 1982, you had one option if you were interested in irreverent comedy at 12:30, and that was David Letterman.

A whole generation of people who like this kind of thing were able to share it with each other, which is part of the the reason I knew this was a book that needed to be written. I’ve reported on comedy for a while now, and in talking with comedians, comic actors and all other kinds, I realized I was far from alone in terms of my having been influenced by Letterman. He’s like a baseline that so many people, whether it’s Billy Eichner or Judd Apatow or Jimmy Kimmel. It’s something they and so many other people all share in a very fundamental way. To properly understand comedy right now, you need to understand David Letterman.

Then again, I could argue the counterpoint as well. I mean, even though everything has become fragmented, it also means that Late Night — both Letterman’s variety and its successors — can now reach more eyeballs via YouTube and other online means. I mean, consider “Carpool Karaoke.” Even though ratings are low for James Corden’s The Late Late Show and similar programs across the board, his “Carpool Karaoke” sketches reach massive numbers that dwarf the competition when it comes to YouTube or viral video viewings. Maybe Colbert will grow in stature, but who knows? I don’t think it’s all just fragmented. I mean, the culture is very fragmented, but it’s also that because late night shows have become all about viral videos and short clips. Again, this is an argument with which I think people will disagree, but I think that when you shift the kind of flow from a cohesive hour of comedy and personality and talk to a collection of parts that don’t necessarily all tie together, the ambition of it all will inevitably decline.

A comparable point is the talking aspect of late night talk shows. I mean, they’ve always constituted a small portion of late night programming, but it feels like these bits have become smaller, and less emphasized, with time.

I agree.

This was something I talked with Chris Hardwick about at length when he was promoting his new Talking show on AMC. Perhaps today’s audience isn’t interested in these kinds of longform conversations in late night programming, though I know I am. I’m sure others are, too.

Exactly. Let’s say he’s not successful. Let’s say that’s an anomaly, and essentially — which I think already has happened — TV realizes that podcasts are going to do long form conversations better than they ever will. What are TV shows to do? Chances are they’ll double down on trying to produce bits that go viral. They’ll make the occasional longform interview on shows like Charlie Rose. Yet my argument about the fragmentation of culture doesn’t just have to do with the audience. It has to do with content. I think, aesthetically, we’ve moved into these places where you have podcasts on the one side, and with a smaller audience, and you have television and its audience on the other side.

The thing about Letterman and these older shows is, they were trying to do both at the same time. Consider the late Letterman. I think he was a supremely gifted conversationalist and a great talker, a great monologist. Not the opening monologue with jokes, but in terms of spinning a yarn in the style of old radio. He was great at that, mainly because radio is where he got his start. He loved radio as a kid, his first job was radio, and his introduction to broadcasting was in terms of radio. I think you really see this in his performance style. He really loves language, and he respects those classic radio whizzes.

Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night is now available in hard copy and digital editions at Amazon or wherever books are sold.