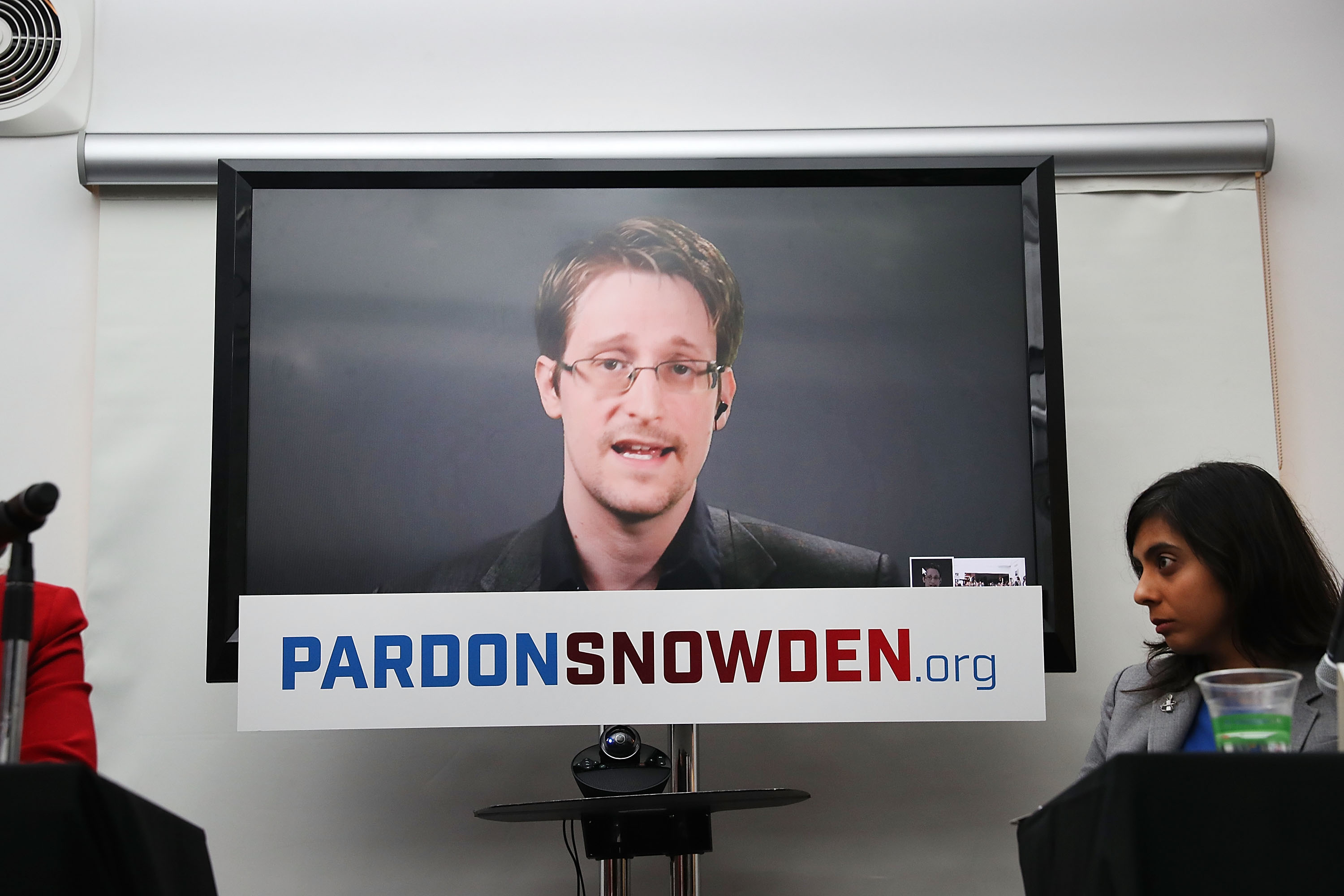

Edward Snowden occupies a strange place, culturally, right now. At the same time that Kenneth Roth of Human Rights Watch and Salil Shetty of Amnesty International are calling for him to be pardoned in a New York Times op-ed where they call his actions a “public service,” a summary report from a two-year House intelligence committee investigation has dismissed the idea that he is a “whistleblower” and (perhaps unsurprisingly) painted him as a “disgruntled employee.” This all as a movie about his life has been made with Oliver Stone, an Oscar-winning director, at the wheel. The result of all of this is (and it’s fair to assume that the concerted campaign to get him a pardon and the release of the film are, at least, loosely connected) that, yet again, Edward Snowden’s name can’t help but find its way into the headlines.

Snowden, who is living in exile in Russia presently, is doubtlessly a symbol. His face turns up in street art and on items as diverse as pins, lego figures, statues, shirts, and prayer candles. If you want to apply a simple comparison, he’s the Che Guevara of the cyber set; a revolutionary that is, rightly or wrongly, idolized by a growing flock with over 2.35 million followers on Twitter. In the halls of power, there’s a little less love and affection, but his name can still be thrown about with pleasure or disgust when talking about national security. Presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump want to bring him to justice. Former candidate and U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, on the other hand, wants to find a way for Snowden to avoid a long prison sentence.

Is he a patriot or a traitor? That’s a question that a lot of people have an opinion about, and that’s before people flock to see the movie and become insta-experts. Patriot or traitor, the one undeniable fact is Edward Snowden has become the story, but what does that say about his actions and about us?

Infamous Before Famous

The fascination with Snowden is justified, to some degree. In the summer of 2013, Snowden, a former NSA employee, disclosed thousands of classified documents to journalists Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Ewen MacAskill. He then helped curate them to find the most important information that they felt the public needed to know. Among the revelations was PRISM, a surveillance program that captured personal data from millions of Americans. In theory, the NSA wasn’t supposed to be surveilling Americans at all, as they needed at least “51% confidence” that the person they were surveilling was a foreign national. Other revelations included reports that the NSA was watching foreign leaders such as German chancellor Angela Merkel and even the Pope and that there have been instances of workers who stalked ex-lovers. Snowden also accused the NSA of abusing its power to riffle through nude selfies.

The sheer enormity of all of this was, and remains, troubling. Snowden laid bare an entire government infrastructure that most of the world had no idea existed, that had in effect no accountability to American courts or law, and that was paid for by government tax dollars.

The full fallout of the PRISM revelations is arguably still unfolding. A few years later, Apple fought the FBI’s efforts to open a back door into their products in an effort to protect the privacy of innocent civilians. Snowden put privacy, security, and encryption on everyone’s lips, and made everyone ask how much we’d given up in the name of convenience and security. Journalist Jay Rosen summed it up by coining the term, The Snowden Effect:

Beyond this, there is what he set in motion by taking that action. Congress and other governments begin talking in public about things they had previously kept hidden. Companies have to explain some of their dealings with the state. Journalists who were not a party to the transaction with Snowden start digging and adding background. Debates spring to life that had been necessary but missing before the leaks. The result is that we know much more about the surveillance state than we did before. Some of the opacity around it lifts. This is the Snowden effect.

It helped that Snowden’s tale was to some degree the stuff of a classic spy drama. If it weren’t a true story, one could imagine a novelist spinning it out on the page. But the enormity of the act is, more often than not, eclipsed by the man himself.

The Making Of An Idol

It’s fair to say that human nature has played a role in Snowden’s reluctant celebrity. Part of it is inherent to the media: Journalism may be focused on facts, but media, by and large, is obsessed with narratives and sides. Talk shows don’t thrive on shades of gray, but rather, they are powered by for or against, pro or con. Another problem is that talking about Snowden is easier than talking about what he revealed. The documents he disclosed are shrouded in an information war, a murky reality where questions of liberty have been poorly considered and an American intelligence agency spied on the taxpayers funding it with no accountability. It’s much easier, and less controversial, to talk about Snowden instead, and that’s exactly what has happened.

Immediately after his name hit the papers, Snowden’s actions were subsumed by the man himself. You can see it, a bit, even in Rosen’s quote above. “The Snowden Effect” isn’t anything new, and Snowden would likely be the last person to claim such a thing. Much of what we know about the behind-the-scenes machinations of the Vietnam War, for example, are courtesy of whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, who pulled back the curtain on the deceptions the Johnson administration engaged in both with the public and in Congress. And, yet, too often, the discussion is focused on Snowden himself, or the morality of his actions, to the point where it consumes articles that are focused on the genuine news or the philosophical meat of Snowden’s actions.

The Washington Post’s overview, and criticism, of President Obama’s pointed remarks on Snowden is titled “Edward Snowden, Patriot.” John Cassidy’s otherwise excellent breakdown of the Snowden revelation for The New Yorker is titled, “Why Edward Snowden Is A Hero.”

Cassidy’s more critical colleague, Jeffrey Toobin, responded by speaking about Snowden’s character rather than interrogating the facts in a rebuttal.

So he wasn’t blowing the whistle on anything illegal; he was exposing something that failed to meet his own standards of propriety. The question, of course, is whether the government can function when all of its employees (and contractors) can take it upon themselves to sabotage the programs they don’t like. That’s what Snowden has done.

This has led, in turn, to an even stranger phenomenon. A man who wanted nothing more than to expose a serious problem with our intelligence gathering has become, like it or not, a celebrity.

One of the more interesting interviews with Snowden came, ironically, from a comedian. John Oliver flew to Russia and confronted Snowden directly about some major issues that his leak caused on Last Week Tonight in what’s likely his most substantive video interview. What’s most telling about the clip, though, is how Oliver bemoans just how little people care about the substance of it all. When Snowden tries to talk about the ethical issues around foreign surveillance, there’s this exchange:

Oliver: Domestic surveillance, Americans give some of a sh*t about. Foreign surveillance, they don’t give a remote sh*t about.

Snowden: Well, the second question is, when we talk about foreign surveillance, are we applying it in ways that are beneficial…

Oliver: No one cares.

Snowden: -In terms-

Oliver: We don’t give a sh*t.

Snowden: We spied on UNICEF. The Children’s Fund.

Oliver: Sure.

Snowden: We spied on lawyers negotiating…

Oliver: What’s UNICEF doing?

It’s brutal, but a little fair.

When searching for polls about Snowden, you’re more likely to find opinions about his heroism and how he’s viewed around the world, rather than how people feel about the work he’s done. Even when Snowden presented a new tool for protecting the anonymity of journalists recently, the focus was on his video stream, not the item itself.

Snowden will take absolutely any opportunity to educate the world about privacy and digital security, weighing in on debates, speaking to the media, and even chatting with teens on Twitter. But pop culture stardom in the form of Obama poster parodies, New York street art, and listicles about him as an ‘icon’ are clearly not what he had in mind.

Perhaps the most glaring example of iconography overwhelming fact is the previously mentioned film from Oliver Stone, who Uproxx film critic Vince Mancini notes delivers “generic” relationship “drama” between Snowden (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and his girlfriend (Shailene Woodley), but fails to “understand the big picture issues of the story he’s telling.” Edward Snowden assisted with Oliver Stone’s film, but he had no script approval. Officially, the movie is based on The Snowden Files, a book by Luke Harding, who hadn’t spoken to Snowden when he wrote it, and a novel written by Snowden’s lawyer.

Why does this all matter? Here’s a worrying PSA from Oliver Stone as a part of a tongue-in-cheek ad tied to the release of Snowden that instructs people to turn off their phones (while they’re sat watching a movie).

While Stone isn’t necessarily wrong about the possibility that the information you put into the world on your smartphone might “burn your life to the ground,” the tone — which implies that Susie and Johnny Cellphone User are doomed to be hauled off to Gitmo — is a problem. Surveillance overreach as a campfire tale about big bad brother standing outside your door with cuffs and a black hood feels like fiction, but this stuff is real and terrifying. We can’t allow people to forget that and file these things away in tidy boxes. We should never forget the human side of this story.

The Opposite Of Notoriety

Just like Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning revealed some truths that the government would have preferred to have kept hidden. In 2010, Manning revealed, via WikiLeaks, botched operations that killed two journalists in Iraq and dozens of civilians in Afghanistan. She confessed her actions to a friend and was arrested by Army Counterintelligence, where she was court-martialed and is serving a thirty-five-year sentence. While imprisoned, Manning has attempted suicide, been denied communication with her attorneys and editor (who weren’t sure if she was alive), and she recently went on a hunger strike in an effort to draw attention to her treatment in prison.

What Manning did was just as important as Snowden’s actions. Violating human rights on that scale is something governments need, desperately, to be held accountable for, and if she hadn’t acted, the U.S. government would have just marked the footage classified and walked away. Yet, you’ll never hear about Manning from the press when issues of surveillance come up. But Manning doesn’t have a biopic from an Oscar-winning director on the way to plead her case, or street artists building statues, and she has slipped further and further from the public eye. Does she not fit the mold of some people’s view for what a cyber activist hero should be because she got caught and is wasting away in prison? Does it have to do with the fact that she is transitioning from male to female? Regardless, the impulse to forget Chelsea Manning while celebrating Snowden (who has done his best to draw attention to her plight) makes clear the heavy hand perception and luck player in how the media and the public at large casts its angels and its demons, all while the truly onerous sh*t fades into the background.