It’s a cliche that people never get their flowers while they can still smell them, but it’s a cliche for a reason. The rap game has failed to honor its true pioneers seemingly forever; the mainstream music world even more so. However, at the 2018 Grammys, improbably, both have the opportunity to give one of music’s true innovators and trailblazers his just reward for bringing hip-hop from the block to the boardroom. Best Rap Album is fine, but we’ve already argued why Jay’s recent Roc Nation signee Rapsody should win that. Jay-Z’s 4:44 is nominated for Album Of The Year, and anything less than a win is simply unacceptable. 4:44 is just too special not to win.

Here’s the thing: Much ado has been made of Jay’s growth on-record, his vulnerability, his social awareness. But the only real reason anyone is making such a big deal out of it is they don’t know Jay. These have always been features of the rap impresario’s approach to his music. The problem is, it’s been so long since Jay has sounded like Jay, everyone forgot. 4:44 isn’t great because he’s doing anything new; it’s great because it’s the first time in a long time he’s sounded like the guy who made Reasonable Doubt, The Blueprint, The Black Album, or American Gangster.

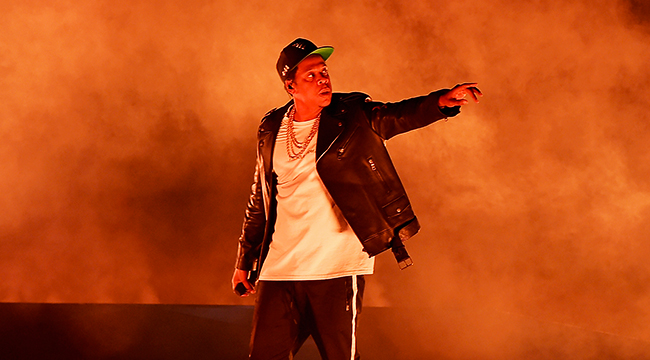

That guy was confident, smooth, laser-focused, and swaggeringly self-assured. Sure, there have been missteps along the way — how could there not be? We’re talking about one of the most prolific personalities in the rap game for over two decades. Jay-Z pioneered the modern oversaturation model in many ways. His relentless “one album a year” release schedule meant that some duds were sure to sneak through the quality control process (Kingdom Come, anyone?). However, he was always sure to bounce back, never really experiencing a serious rut in creativity or inspiration like the one he’s had in his recent, later years.

Starting with 2009’s The Blueprint 3, Jay’s went on a three-album run of mediocrity (including the collaborative Watch The Throne, on which Kanye West was almost indisputably the better half) where he sounded unsure, uninspired, worn-out, and dare I say, washed. Instead of sparking trends and setting hip-hop’s agenda for the next year-and-a-half as he’d always done, he went on a frustrated tirade against Autotune, a position that only lasted until his next opportunity to pop up alongside the toasted artist du jour — which happened approximately five songs later. On “Off That” with Drake, he dropped the crotchety anti-Autotune stance but picked up a list of new grievances to rail against, wasting an early opportunity to pass the torch gracefully, keeping one hand on the hilt.

When he returned with Magna Carta Holy Grail four years later, it seemed like he’d moved so far past complaining about hip-hop that he’d actually left hip-hop behind, despite a masterful marketing strategy that proved his business prowess. Instead of guiding the rap game from within, he paternalistically hurled directives from atop an ivory tower built on Eurocentric works of art that he’d eschewed and disclaimed less than a decade previously. Yet, what did kids in 2013 care for Tom Ford luxury and Picasso paintings? Such things may as well not even exist to a kid from Brooklyn’s Marcy Projects, which Jay-Z hails musically as his origin but all but forgot on Holy Grail.

As it so often does, it took a brush with disaster for Jay to regain the perspective that years of standing on the lonely mountaintop of rap success had dulled. He had it all; accolades, fortune, fame, and “the hottest chick in the game wearing his chain.” It took his own pride, ego, and fragile male insecurity nearly dashing the last of these away for him to realize he had nothing left to prove. True, the rap game no longer needed him, as he once boasted was the reason he couldn’t leave it alone. But instead of reading that as cause for desperation or depression, his errors with Beyonce shuffled his priorities; he could take or leave rap, just as it could him, but he loved the game too much to simply walk away.

He’d already proved that after his aborted post-Black Album retirement. He just had to find his own reason to rap again and something to rap about. Simply put, he had to find the old Jay-Z, the one who stayed up late nights driving his mother and siblings crazy beating on the kitchen table as he honed his craft for no other reason than the pure joy of stringing together rhymes to wow an engaged audience.

And so he did. On 4:44, Jay doesn’t just rap about Black empowerment through financial independence or social consciousness. He doesn’t just lay his soul bare regarding his indiscretions and insecurities. He does so well, with all the creativity and light-hearted conversational nature of his best works.

The reason Jay’s rhymes were considered top tier wasn’t because they were so much better objectively than those of his contemporaries; he’d be the first one to tell you that himself. He never stood head-and-shoulders above his peers and rivals due to his diction or insight. He did so through force of personality. He did so with his wit and charm that disarmed and drew listeners in. He didn’t just rap; he talked to you, like an old friend or a sage relative relaying some polished gem of hard-earned wisdom. A Jay-Z song felt like a conversation, as if in the spaces just after particularly salient bar, you could add your response to be addressed in the next one.

4:44 is the first time that Jay has appeared on record in what feels like a lifetime. Indeed, a whole generation of rap listeners hold no reverence for Jay-Z, not because they don’t respect their elders and hate hip-hop history, but simply because the Jay-Z they’ve been given isn’t the Jay-Z who solidified his claim of “Best Rapper Alive” through demonstration, not just declaration.

4:44 brought that Jay-Z back, and because of it, he’s not only provoked a legitimate discussion about aging gracefully in rap but also demonstrated its possibility and provided the blueprint to do so. If for no other reason than granting Jay another chance to be relevant in rap while pushing the genre’s existential boundaries — even if it’s only one last time — 4:44 deserves the highest award the music industry has to give. Jay’s career is still alive, against all odds, let’s hope the committee sends him out on a high note.