As someone born in the eighties, my first exposure to Midnight Cowboy was as a joke on Seinfeld that I didn’t get. Jerry and Kramer were on a bus, Kramer slipped into a weird accent and started acting pathetic and all of a sudden some music kicked in and my dad was laughing much harder than I was. “They’re doing Midnight Cowboy!” he said, as if this was something a teenager should just know.

Amazing how jokes you didn’t get will stick with you like that. Yet in the 20-odd years since that Seinfeld episode, I still hadn’t ever seen the 1969 Best Picture winner (the only X-rated film ever to do so) and number 43 on the American Film Institute’s 2007 list of best American films. What can I say, we didn’t have streaming services back then. But now Midnight Cowboy is available free on Amazon Prime and all the movie theaters are closed and so here we are.

One great thing about watching old movies in the age of streaming is that they look fantastic. Watching on any decent modern TV, you get a sense of how it must’ve felt to see them during their original run in a way VHS or even relatively recent DVDs never allowed. Digital technology has only barely caught up with what film projected in its original format could accomplish in the 1930s. I can’t say the same for flat screen sound, but that unmistakable Midnight Cowboy song (“Everybody’s Talkin,” by Harry Nilsson) kicks in right away. Jangling guitars, lyrics that you can kind of understand that trick you into singing along — definitely don’t watch if you’re not prepared to have it stuck in your head for a week. Midnight Cowboy is almost more song than movie.

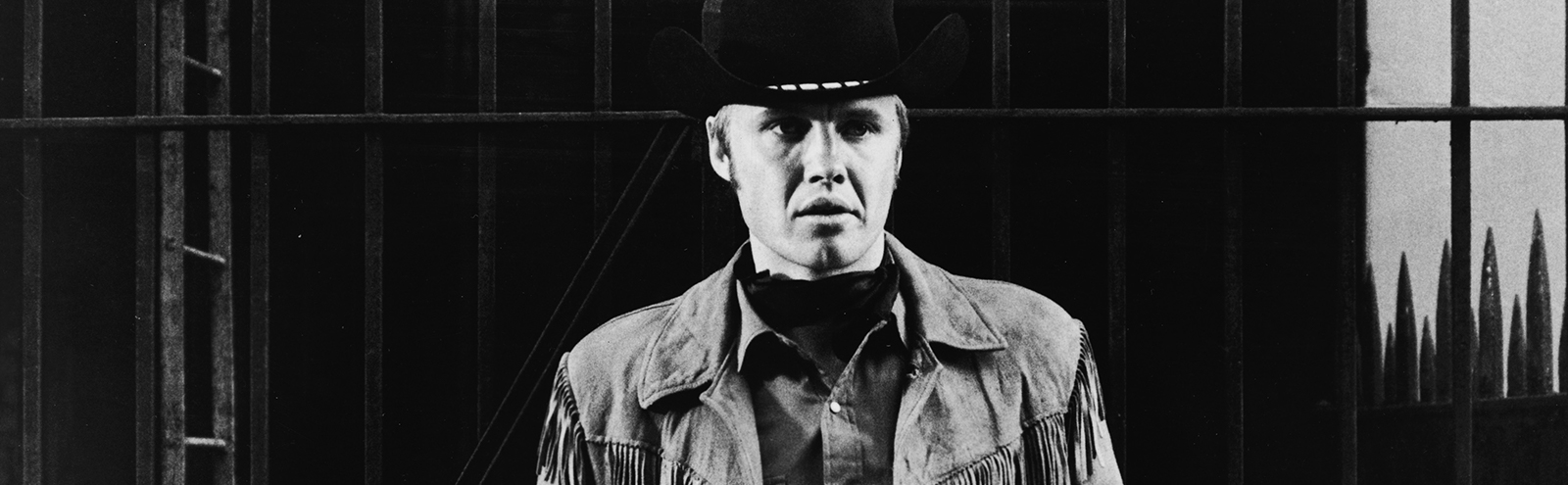

We open in small-town Texas, following a jarringly handsome Jon Voight (at least compared to the present-day MAGA incarnation) as Joe Buck, a cosplay cowboy who has quit his dishwashing job to set out for the Big Apple. He tells everyone who asks or doesn’t (and mostly they don’t) that he’s going to become a “hustler,” which apparently means pleasuring older ladies for money. Joe Buck is either a lovable idiot or working hard to give the impression of one. His plan is plainly quixotic but he does have two things going for him: irrational optimism and total commitment to a look. He apes wholesome TV cowboys and assumes panties will simply melt away for him, something that makes perfect sense in his mind.

Directed by John Schlesinger (who went on to direct Marathon Man and Pacific Heights, among others) and written by multiple Academy Award winner Waldo Salt (from the novel by James Herlihy), Midnight Cowboy’s most obvious contribution to pop culture was this oddball lead, whose echo I recognized for years without knowing it, from Seinfeld to Don Cheadle’s cowboy phase as “Buck” in Boogie Nights. Even Woody in Toy Story feels like he has a little Joe Buck in him.

Of course, Buck’s entire character in the first place is that he’s derivative, a tumescent Don Quixote determined to sell Americana back to horny housewives, flipping the script on Manifest Destiny — go east, young man! His most prized possession is his hand-held radio, embodying an America seduced by its own media myths and high on its own supply. Clearly they’ve done a symbolism here.

The rub is that no one’s buying. Joe Buck, whose multiple attempts at sidling up fail to produce any partners on the bus ride to New York, does manage to score with a voluptuous older rich lady (Sylvia Miles) soon after he arrives, even despite his absurd pick-up line: “Ma’am, I’m new in town, can you tell me how to get to the Statue of Liberty?”

But when he tries to ask her for money, she gets so upset that Buck ends up giving her money, some of his last few dollars for her cab fare. Eventually, Jon Voight meets his co-star, Dustin Hoffman, sweaty, greasy, and with caked-on tooth grime as Enrico “Ratso” Rizzo. Ratso walks with a (slightly over-the-top) limp, calls himself a cripple, and seems to suffer from various other unnamed ailments (possibly tuberculosis?). He promises to set up Buck with a pimp who will help Buck realize his gigolo dreams, but the guy turns out to be a closeted religious freak and the whole thing a setup for Ratso to bilk Buck for $20. Despite it all, they manage to become friends.

The Jewish Hoffman playing the notably Italian Ratso is clearly intended as a greasy, sickly, worldly, duplicitous, overtly rat-like Southern European foil for the notably corn-fed guileless Aryan dope, Buck. Only instead of this model American myth man lifting the sickly ethnic type out of poverty, it’s the other way around. They move in together in a condemned squatter’s apartment, eating frozen Campbell’s soup and stolen coconuts, while Ratso gently tries to get Buck to drop his cowboy shtick, pointing out that it’s already a gay prostitute cliché. Buck is baffled, almost in tears yelling, “You’re gonna tell me John Wayne is a fag?!”

The movie essentially has multiple versions of this revelation, and the one where Joe Buck walks around Time Square, wordlessly reckoning with scores of young handsome studs dressed just like him, is a lot stronger than the melodramatic yelling version. Throughout, we get flashbacks to Joe Buck’s Texas life and clues as to what made him this way. The love of his life (possibly the town slut) was gang-raped by angry rednecks for unclear reasons while he was forced to watch; his weird, quasi-sexual relationship with his grandmother, who gave him money for massages. Angry reactionaries and sexless suburban ennui, the twin scourges of the Beats and Boomers.

At one point Joe and Ratso end up at a psychedelic Andy Warhol-type party (look, the counter-culture!), where drugs and food are free, and Joe Buck’s invented identity makes him fit right in. A lady even agrees to pay him for sex, probably because it seems almost like performance art. Unfortunately, Ratso can’t enjoy the party because he’s so sickly and pathetic, even turning down the party host’s generous offer of a shower (to the chagrin of the viewer, wishing he’d brush his teeth as soon as he appears).

Eventually, the two set off together after a mirage, spending their gigolo loot on a bus to Miami, where Ratso has always dreamed of going, in an idealized, tell-me-about-the-rabbits-George kind of way. Naturally, he dies right when they get there, still on the bus, making clear what we assumed from the start — that this character’s ultimate purpose was to die tragically.

Midnight Cowboy reminds me of a lot of other movies from this era (Easy Rider, Bonnie And Clyde) whose impact has dulled in the years since it was hailed as a landmark (it slipped from 36 to 43 on AFI’s list of best American films between 1998 and 2007, for whatever that’s worth). Simply depicting the counter-culture counted as innovative in those years (“Hey, here’s the counter-culture!”) and while Midnight Cowboy does have the whiff of insight about it, it’s fairly broad, in the seeing-how-the-other-half-lives/America is a land of contrasts mold. I’m still not quite sure why Ratso is so pathetic, and a lot of Hoffman’s choices feel very “because acting!” Think Scotty Templeton from The Wire, talking about “highlighting the Dickensian aspect.”

In 2020, Buck and Ratso feel overly obvious as foils, and the ironic failure of Joe Buck’s big plan (followed by its ironic success) feels… again, kind of obvious. Of course, he wasn’t going to make money having sex with rich women. Of course, his shtick only made sense in the gay community. The gay subtext of Ratso and Joe Buck’s relationship is the most interesting part, and one of the few themes about which Midnight Cowboy plays coy (perhaps understandably, for the time, it still managed to get an X rating).

And. of course, movie hippies were always getting murdered (or raped) by rednecks in the sixties and seventies for reasons more symbolic than believable (not necessarily literal hippies, but certainly the free-spirited protagonists they would’ve identified with). It feels a little like foreshadowing for “the terrorists hate us for our freedom,” where Boomers are just the presumptive heroes of reality and thus their enemies don’t warrant motives (“they hate us for our virility!”). There’s a painful poetic symmetry to Jon Voight becoming a Trump guy. It also makes the central joke of that Seinfeld episode, that George had bought a Chrysler Lebaron that had once belonged to Jon Voight, hit so much harder.

Yet Midnight Cowboy operates on a level of the poetic, with broad strokes and memorable theme music, and a weirdly watchable performance by Voight. It evokes a time and a place even for those of us who never lived it. That’s what I mean when I say it’s almost more like a song than a movie — it has the power to remind you of a certain time and a certain feeling, even if the feeling doesn’t necessarily require or stand up to examination. And for all its faults, one can’t deny that fake cowboys expecting to get laid because of TV are still all around us.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.