When Steve Jobs died in 2011, the collective mourning that took place around the world was overwhelming. People congregated to Apple stores like it was their mecca, dropping off bouquets of flowers for a man they never knew. Virtual flames, projected off iPads, flooded the sky. iSad became the easiest way to express sorrow via social media for those who were at a loss for words on how to grieve. People took to their webcams to express their loss and extol the magic Steve’s product brought to their lives. But it wasn’t necessarily Steve they loved — they didn’t even know him. They were in love with what he had created.

Perplexed by this outpouring of remorse usually reserved for the likes of rock stars and political figures, Alex Gibney began work on a documentary to show the real Steve Jobs. Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine shows us the man loved by many, how his products became an extension of ourselves, and the often ruthless behavior he adopted on his way to creating a powerful company.

Through interviews with people who worked closely with Steve, those who had personal relationships and children with him, and the journalists who reported on Jobs and Apple, Gibney reveals the darker side of Steve. It’s like watching a doc on a cult leader and his brainwashed tribe, harking back to Gibney’s Going Clear. And if you go outside at any point today you’ll no doubt see a smattering of people clutching their iPhones, showing us that although Steve has died, what he has left us with certainly takes precedence in our lives. I spoke with Gibney while he was en route in a bulletproof limousine. He joked, “We’re worried about the Mac people nearby who have been toting machine guns. We’re concerned about our security.”

What has been Apple’s reaction to this documentary?

The only thing we’ve heard is a tweet that Eddie Cue made after the premiere at SXSW, which is something like, “It’s a bitter portrait of Steve, not the man I knew.” Something like that. But there has been no official reaction from Apple. Though I know from people inside that they’re concerned about it.

That one sentence alone speaks to the cult aspect of Apple. He’s still so inside of it, that he is protecting Steve.

Yes, I think that is true and that’s the aspect of it that I think is so cult like. One of the women we interviewed in the film, the journalist Yukari Kane who wrote a book about Apple, the Haunted Empire, and she meant that it was still haunted by Steve Jobs. The view is you can’t say anything that’s critical of Steve Jobs, it’s a blow against the cult. It’s like speaking against L. Ron Hubbard.

Right, especially when you talk to people who were a part of Apple and now that they no longer work there, they’re able to say how they really feel. I loved Bob Belleville [Director of Engineering, Macintosh ’82-’85] he’s so sweet.

So sweet and I think of him as the heart of the film.

When he became emotional in that moment, talking about his experience working on the Mac, what did you make of how he was responding to that time in his life?

I think what was interesting about Bob’s response was so deeply mixed. On the one hand I think he really did have affection for Steve, deep affection for Steve. At the same time he also saw how ruthless he was and the cost in his own personal life was so high that all of those things came rushing out of him at the same time. So it was both a magical time for him and a horrible time for him. And it’s taken him years to get past it and recalling Steve, in the piece that he wrote about him when he died, brought all those contradictory emotions rushing back to him.

Did that surprise you? His feelings?

It did, it completely surprised me. We were interested in him because he had been to Japan a lot with Steve and also he was very much a key player in the making of the Mac. So for those two reasons we wanted to talk to him. But we were exploring. We didn’t know exactly what he was going to say and then when he read his eulogy he started to break down and cry. We had to film it three or four times. He had a hard time breaking through.

Was the instigation for this documentary based on those strong emotions people had to his death?

It really was. It wasn’t just a confection that I dreamed up to try to begin the film. It’s really why I started it. It’s very rare when the CEO of a globe girdling corporation inspired that kind of sorrow on his passing. John Lennon maybe. Martin Luther King. But a CEO of a big corporation? It was very unusual. And I thought, why? Why is this? It was just luckily for me CNN let me go forward with the idea of that question just as a rationale for investigating.

And before you started investigating, what did you already know going into it?

I have to say that I didn’t know that much about Jobs. I knew what the average person would know from reading the paper and then I would see things from time to time. But it was only in starting this project that I read the Walter Isaacson book and ultimately I read a bunch of other books, including the book about Steve Jobs and Zen. And then my collaborator on this, Peter Elkind, who I worked on with Client 9 and also Enron, he looked at me critically when we started, like, “Are you sure you want to get into this? So much has been done.” But it was fresh for me so I think that was actually an advantage and then I think there were a lot of people out there like me who knew a little bit about Steve but didn’t know that much. And so it allowed me to begin.

Right, and those people, at the same time, are the ones who mourned him.

Yeah, they were strangers. Of course it’s perfectly understandable that Steve’s family and friends would mourn him. But all these people were strangers. We collected so many of those videos, some of which are used in the film, weeping, looking into their iPhones or the cameras on their MacBook Pros and talking about how sad they were that Steve was gone. Not to mention that kid who was in some kind of euphoria about Steve. The kids says, “He made everything!”

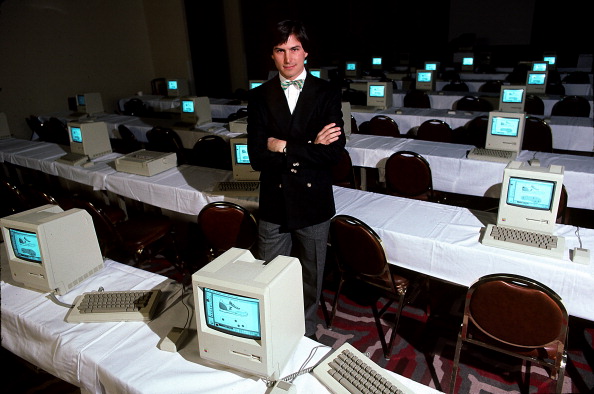

Steve Jobs with room full of computers, 1984. (Photo by Michael L Abramson/Getty Images)

For you, discovering and uncovering these things about Steve, was there anything that disheartened you the most?

I’m tremendously impressed with Steve as a businessman and also his understanding of the connection between human beings and their computers and how he fostered that connection. But what surprised me and upset me the most is how ruthless and cruel he could be, particularly to people who didn’t have that much power, because at that end it was so unnecessary. And that, I think, belied the countercultural values that he’s suggesting Apple represented. And at a time when Apple is the world’s most valuable company that seemed worth exploring.

Are you left liking anything about Steve?

I think that he could be tremendously charming and charismatic and he had a kind of curiosity about the world that was interesting to me. Also, one thing I liked about him is he wouldn’t settle. He had a vision about what a product should be. He was determined to make it that way. And while he wasn’t always singularly responsible, he pushed people to make sure it got that way. I do admire that. Not being willing to settle and to be willing to push forward and get what you believe in and what you want.

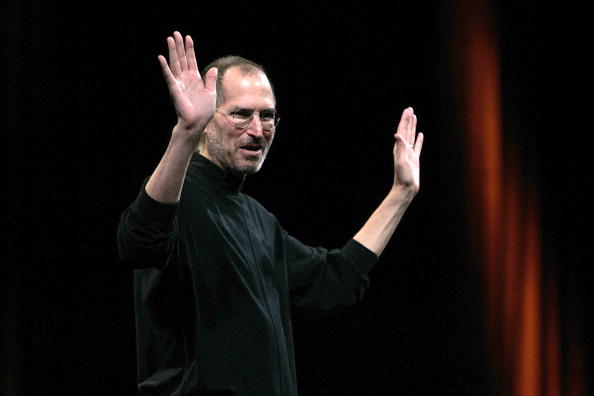

SAN FRANCISCO - JANUARY 15: Apple CEO and co-founder Steve Jobs delivers the keynote speech to kick off the 2008 Macworld at the Moscone Center January 15, 2008 in San Francisco, California. Jobs introduced the wireless Time Capsule backup appliance, iTV 2 and the new ultra thin laptop MacBook Air. (Photo by David Paul Morris/Getty Images)

What’s scary to me, and is shown in the film, is our increasing addiction to the devices Steve gave us. And you made an interesting parallel to our behavior and the film Until the End of the World. What do you think of what he’s left us with? Did he leave us ultimately with a bad thing, that we are unable to disconnect from these products?

I think his legacy is contradictory. I think it did help to create a relationship between machines that extended ourselves and really was a bicycle of the mind. At the same time he created these devices that, like Steve, were truly isolating. And there’s no simple answer to that. But it demands that we think about it. Because they’re not just purely good. There’s a lot about these devices that are terribly damaging and gets us further and further inside our own heads instead of allowing us to look at the world around us.

(Steve Jobs: Man in the Machine opens nationwide on Sept. 4.)