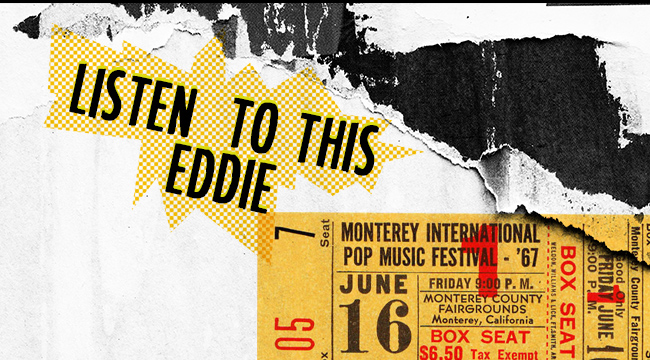

Listen To This Eddie is a bi-weekly column that examines the important people and events in the classic rock canon and how they continue to impact the world of popular music.

Next month marks the 50th anniversary of the Monterey Pop Festival, one of the greatest live events in the history of popular music. To mark that historic milestone, Goldenvoice, the same company behind Coachella, has teamed up with Monterey’s founder Lou Adler for a new iteration of the iconic festival. Dubbed Monterey Pop 50, the festival will take place at the exact same fairground as the original. Instead of Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding and Janis Joplin, wristband-wearers will be treated to the likes of Father John Misty, My Morning Jacket and Kurt Vile. Phil Lesh from the Grateful Dead and Eric Burdon from the Animals will be there too, so that’s something.

Before 1967, there simply wasn’t anything quite like the Monterey Pop Festival. It’s incredible to consider now, because of how monetarily important the larger festival apparatus has become to the music industry as a whole, but the driving force behind the original event wasn’t financial gain. Monterey Pop was actually a charity benefit; one whose impact endures to this day.

The reason the festival came together in the first place however had everything to do with a perceived credibility gap between rock and other genres like jazz and folk. Late one night in 1967, Adler was kicking back at Cass Elliot’s house with Paul McCartney and the rest of the Mamas and the Papas. The conversation eventually turned to the state of rock itself, with the group grousing about how it was treated as a second-class genre by the cultural elites.

Shortly after that evening, Adler was approached by a couple of businessmen who wanted to know if he’d be interested in helping them put together a single-day blues and rock showcase featuring the Mamas and the Papas at the Monterey County Fairgrounds, a site just about two hours south of San Francisco. That’s when the wheels started spinning.

“Later that night — actually at three o’clock in the morning — [Papa’s singer] John [Phillips] and I decided, influenced by some heavy ‘California dreamin’, that it should be a charitable event,” Adler remembered in the book A Perfect Haze. “John and Michelle [Phillips], Paul Simon, Johnny Rivers, Terry Melcher and I put up $10,000 a piece. With six weeks to go, the Monterey International Pop Festival, a three-day non-profit event, was becoming a reality.”

Good intentions and grand visions are one thing. If Monterey was going to be a success, if it was really going to establish rock’s bonafides, they were going to have to put together one helluva lineup. To that end, they established a Board of Governors that included some of the biggest names in the genre in hopes that their added credibility would make it easier to get decent bookings. Paul McCartney signed on. So did Mick Jagger, Brian Wilson, Smokey Robinson, and Roger McGuinn of the Byrds. The organizers set up an office on Sunset Boulevard and began hammering out the details.

The names they put together came from all over the map. The Laurel Canyon scene was represented by the Mamas and the Papas, The Byrds, and Buffalo Springfield. Out of Haight-Ashbury you had the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother And The Holding Company. From New York there was Simon & Garfunkel and Laura Nyro. Then from across the pond in England they got The Who, The Animals, and a hot new group named The Jimi Hendrix Experience. (That last booking was a suggestion made by McCartney.)

Unlike Woodstock two years later, which quickly grew beyond the limits of the promotor’s control, and the Rolling Stones’ fiasco at Altamont, which was never in anyone’s control to begin with, Monterey was smoothly planned and expertly executed. It was one of the first festivals of its kind, but Adler and company ran a tight ship. No detail was too small to escape their notice and attention, whether it was the state-of-the-art stage and sound set up put together by Chip Monck, the coordination among the Monterey Police Department for security, or the 50,000 orchids flown in special from Hawaii.

“For the performers, it was first class all the way,” Michelle Phillips remembered in A Perfect Haze. “The sound system, the travel, the accommodations…and then there was the food. Backstage we had a 24-hour green room with a menu that included lobster, crab, steak, and champagne.” Quite the detour from the cups full of granola doled out at Woodstock. Monterey was Coachella before Coachella, but without the intense heat during the day. The most expensive ticket was only $6.50. The cheapest, just three bucks.

Monterey kicked off on the Friday afternoon of June 16th, 1967 with a performance by a group named The Association. It ended later that night with Simon & Garfunkel. But the first day was merely a taste of what was to come. Things started cooking on Saturday when Canned Heat were given the privilege of kicking things off, before ceding the stage to the aforementioned Big Brother And The Holding Company. If that band name doesn’t ring a bell for you, maybe their diminutive young frontwoman from Texas, Janis Joplin, does. To put it bluntly, Janis wiped the floor with nearly everyone who set foot on that stage. The group’s cover of Big Mama Thornton’s song “Ball & Chain,” left attendees, including Cass Elliot’s mouth on the floor. Her voice and her presence pinned everyone to the back of their chair. Janis came to Monterey an up-and-coming talent. She left a legend.

Most of the rest of that day’s programming was filled out by blues-rock and psych-rock bands like Moby Grape, Jefferson Airplane, and the Steve Miller Band. To close things down, the organizers booked Stax Records standout Otis Redding. He was an odd choice considering the rest of the bill, but Adler and company were looking for diversity in the lineup. Redding put together a set brimming with the kind of showmanship and high-energy that many of these white guy rock bands simply couldn’t match. His charisma was off the charts. In his hands, the Stones’ classic “Satisfaction,” was transformed from an angst-riddled lament to a joyous celebration of life itself. Sadly, Otis died in a plane crash just six months after this performance.

It’d be hard for anyone to match, much less top that level of showmanship, but there was still one figure determined to give it a shot. Jimi Hendrix was a veritable nobody when he left America to chase his dreams of musical superstardom in the UK in 1966. He’d backed up everyone from Little Richard to James Brown for years before he left, but failed to find success under his own name. It took less than 10 months in UK, but everything changed. His record Are You Experienced lit up the charts on that side of the Atlantic, and his chops on guitar put the fear of God in to every six-string player from Eric Clapton to Jeff Beck.

Who guitarist Pete Townshend was keenly aware of what Hendrix was capable of, and wouldn’t you know it, the two acts were booked to perform together on the same night. Back to back in fact. Townshend wanted nothing to do with trying to follow Hendrix’s onstage antics and superhuman musical ability. Hendrix himself had no desire to follow the Who either, who were known for putting together sometimes literally explosive performances. They worked it out with a coin flip. Hendrix lost and would go on later.

Everyone knows how it turned out. It took Jimi all of 45 minutes to write his name into the book of the immortals. The songs “Purple Haze,” “Killing Floor,” and “Foxey Lady,” hit with the force of an atomic explosion. He played with his teeth. He played behind his back. He did things no one in that audience, and no one who watched the subsequent film put together by D.A. Pennebaker thought were possible. It was the final number however, that remains etched in collective memories.

To finish out his set, Hendrix bashed into a haphazard cover of the Troggs’ garage rock classic “Wild Thing.” He played it straight for a few moments, then began to simulate sex, grinding his guitar forcefully against a stack of Marshall Amplifiers while waves of feedback washed over the crowd. At one point, he threw his Stratocaster to the ground, raced to the back of the stage, grabbed a bottle of lighter fluid, doused it, then lit a match and watched as the body of his beautiful instrument turned to ash. He straddled it, coaxing the flames higher with his twiddling fingers, then leapt to his feet, and smashed it repeatedly into the stage, turning it into kindling, which he tossed out into the crowd. Without so much as a goodbye, he walked off the stage and into history.

Monterey Pop set the bar that many of the biggest music festivals across the globe still hope to reach to this day. As a concert-goer, it had everything you could possibly want in a live music experience. Great weather, good vibes, nice sound, tight organization, but most of all, unforgettable performances. Going into it, Adler and company wanted to show the world the best rock music had to offer. He, and every single performer who hit that stage not only achieved that goal, they exceeded it beyond anyone’s wildest dreams.

The Bootleg Bin

I’m a huge fan of live music and live recordings, so, in this section, I want to highlight a specific live performance from the classic rock era that I think it’s worth checking out. You might be wondering why I decided to name this column, “Listen To This Eddie.” I got that title from a very well-known bootleg recording of a Led Zeppelin concert that took place on June 21, 1977. The recording was made by a famous taper in the 1970s named Mike Millard, who would often go to shows in a wheelchair to disguise the intricate recording apparatus he used to capture them for posterity. The name of this particular tape is a sort of tip of the cap to the acclaimed record engineer/producer Eddie Kramer who worked with most of the biggest names from that era, The Beatles, David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and who record Zeppelin’s live album The Song Remains The Same.

The recording quality of this tape is so high, that, whoever ended up putting it together to sell on the black market, thought that Kramer himself would be impressed. As for the content within, though 1977 wasn’t the best year in Led Zeppelin’s career on the road, this ranks as one of the real high points of that particular run. The band always put in a little extra effort whenever they hit Los Angeles, their home away from home, and it shows here on the first of six nights they played at the sold out Forum. Drummer John Bonham is in particularly good form on this particular evening, and the band’s fiery rendition of the Presence album standout “Achilles Last Stand” sounds like the coming of the apocalypse.