The moment I really fell in love with baseball happened as I was wrapped in the arms of a sweaty man whose face has not endured in my memory and whose name I never bothered to learn. This alone is remarkable, as I am shy and skittish to the point that I actively scout for the grocery store cashier who is least likely to speak to me. That anything good could come of physical contact with excitable, strange men is a miracle unto itself.

I was 19 and playing the title role in a national tour of the stage version of a children’s TV show. Unable to go to Real Bars with the rest of the cast, I soon realized that I could, with minimal effort, get drunk sub rosaalongside the beleaguered salesmen populating hotel bars. The year, in case you want to know where this is going, was 2004.

At this point in my life, I had let baseball fade into the white noise of my memory. I grew up on the ’90s-era Atlanta Braves and was so thoroughly dazzled by Greg Maddux that I remembered little else, save for Chipper Jones’ winsome smile and the fact that they called Fred McGriff “the Crime Dog.” I briefly “dated” a guy from Boston, but he was hardly a charismatic ambassador for the then-cursed team. Regardless of his bullsh*t, I remained fairly neutral about the Red Sox. That is, until I began watching baseball with the show’s Bostonian crew members and other traveling fans.

Let me tell you something: I bandwagoned the 2004 Boston Red Sox like a motherf*cker, and I loved every second of it.

Equally compelled by the narrative of their hope and drawn to the spectacle of their desperation, I sat in hotel bars alongside beer-glazed men as they relived the glory and the angst of their childhoods via collective wishful thinking. I became a thrill-seeking lamprey, eager to latch on and drink up. Reader, I bought all the way in.

With my dormant knowledge of the game rushing back to life, I spent October of that year watching the boys from Beantown come back to snatch the 2004 ALCS out of the greedy hands of the Yankees, who had crushed their dreams the year prior. It was not a gentle ride. The Red Sox lost the first two games, and when they lost Game 3 by a score of 19-8, I felt the air in the room turn sour within our mouths. No one had ever come back from a 3-0 series hole to win a Game 6, never mind a Game 7.

We approached Game 4 with the solemn finality of a wake but would nevertheless go forth together as witnesses, whatever heartbreak may come.

And lo, we witnessed one of the greatest postseason comebacks of all-time.

This is why I am a huge proponent of the transformative potential of bandwagoning. The shared joy that I indulged in happened over a decade ago, and yet here I am, still earnestly awash in my baseball feelings. Those Boston fans welcomed me into the agony and the ecstasy of their pathetic history at a time when I was lonely, away from home, and craving some indelible thing.

The rapturous waves of sensation concomitant with that post-season cocktail of hope, fear, and total powerlessness is one best shared. It is too strong to enjoy alone, and though it is made more potent by experiencing it with others, it is also made somehow more bearable. Pleasurable, even. This has to do with they way faces around you affect how you feel.

We’ve all experienced how our feelings can be intensified when we are with others who feel the same way. Fergus Neville, a social psychologist at the University of St. Andrews, explained to The New York Times that his research suggests it’s because when we see our own emotions reflected in the faces of others, what we feel is not only intensified but validated. This is part of why screaming your throat swollen next to a bevy of similarly inclined friends of circumstance feels so easy and good, but screaming alone in an Applebee’s lacks the same catharsis.

Crowds do more than just amplify; they also provide the context for how we process what we’re feeling. Humans rely on emotional and social clues to process the physical sensations of our feelings. Called the two-factor theory of emotion, it holds that what you feel is based on physiological arousal (what your body is doing) and a cognitive label (what you make of what is happening). The biochemical cascade for arousal is quite similar across the board; things like first-date jitters and getting pulled over by a cop are physiologically very similar. We experience them differently because, once the ol’ adrenaline starts pumping, the mind uses environmental context clues to decide how we feel about what is going on. Is it pleasurable, perhaps beneficial arousal? That’s known as eustress. Is it going to be a problem? That’s distress.

The amount of anxiety and worry over a postseason game can easily blur the line between eustress and distress, which is why many people hate watching big games alone. Take the neurochemistry of game day nerves and nestle it in a crowd of other fans who are experiencing the same. Together we can elevate our excitement and feel the whole of our emotions more enjoyably. The crowd is telling your brain that it’s okay that your body feels like it needs to run from a lion. The crowd is there with you. You are in this together. Humans are such social animals; we truly live for this sh*t.

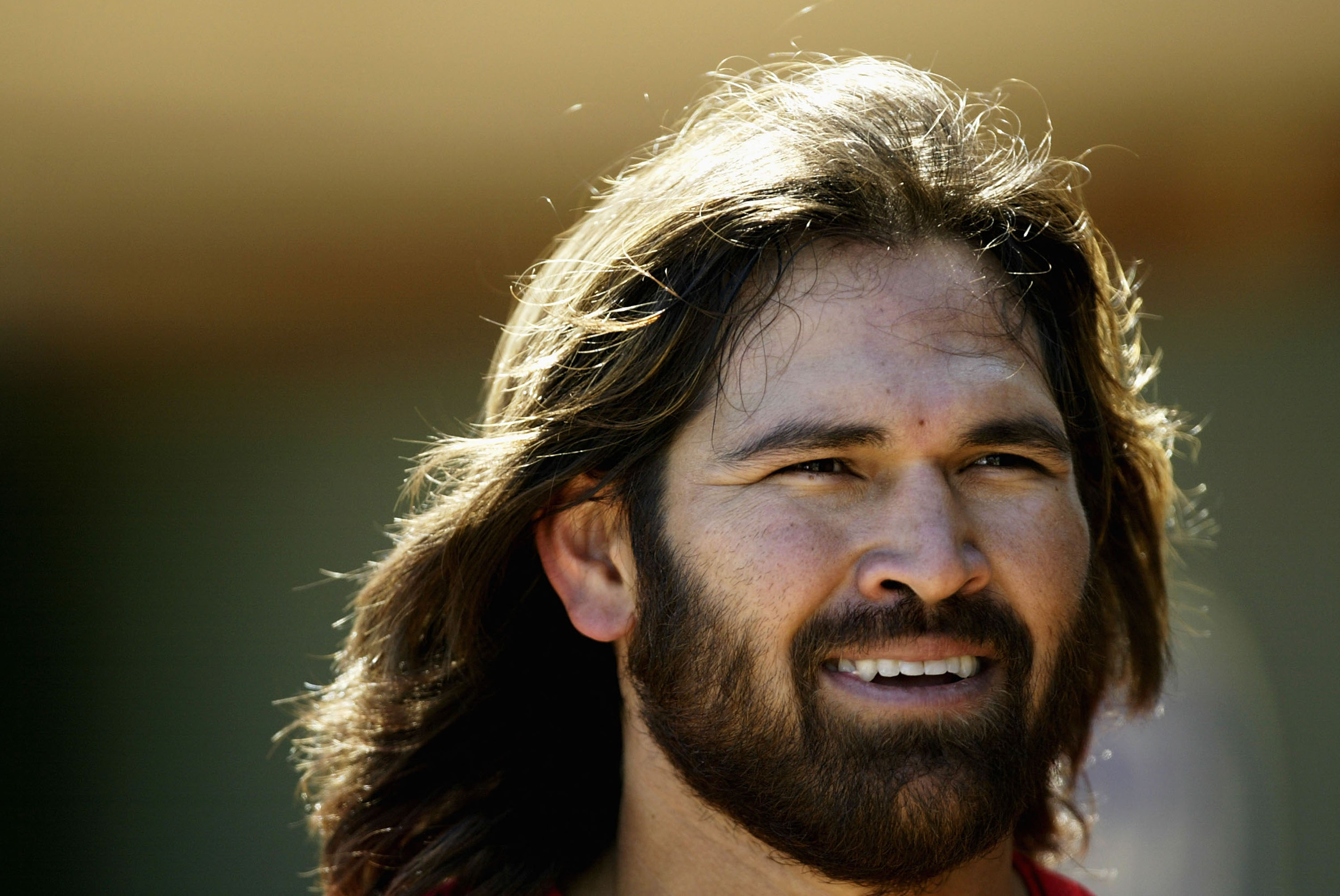

When that Game 7 in 2004 came to be, after all of the angst and the dreaming and the rally caps and the extra innings, we–the collective organism of baseball fans gathered in a dimly lit hotel bar–were a frantic mess. Boston put up two early runs with ease, and soon the bases were loaded. To the plate stepped Johnny Damon, all easy charisma and hair. No one in the bar dared blink, let alone breathe.

And then, suddenly, everything was different.

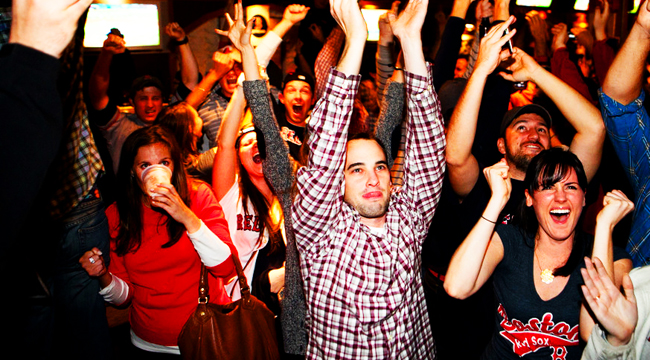

The sound that followed the crack of that grand slam was one of the sweetest and most wholesome things I’ve ever heard. An entire room of people screaming and swearing, picking each other up off the floor, spilling their beers and shrieking with glee. I was swung around like a sack of potatoes, my teeth chattering amid the rush of group euphoria. In that singular moment, it seemed that this might actually be possible. That the Boston Red Sox might finally lift their curse.

And of course, that’s exactly what they went on to do.

I’ve never seen the postseason from the close remove of the stands, never mind had the fortune to see a World Series game in person. But that moment, in that bar, with those strangers… That was one of the most perfect baseball moments I can possibly imagine.

Even now, at just the thought, I am covered in chills.

Leigh Cowart is a freelance journalist specializing in bodily horror and strong feelings. Her work can be found in Hazlitt, The Washington Post, Deadspin, and elsewhere. You can follow her on Twitter @voraciousbrain.