David Simon’s latest six-hour miniseries, Show Me a Hero, directed by Paul Haggis, was an important, incredible, fascinating, infuriating and sad account of a six-year period in the city of Yonkers, New York. It’s a story about public housing, and because of that, I know that very few of you reading this will actually ever get around to watching the miniseries (which is streaming on HBO NOW), as noble as your intentions to do so may be. It was little seen when it broadcast on HBO (less than 500,000 viewers tuned in each week), there were no antiheroes, meth manufacturers, beheadings, red weddings, serial-killers, or orgy scenes. It’s not exactly the kind of series that attracts a huge audience.

But it’s an important story, and one that everyone should know about whether they watch the mini-series or not. In a nutshell, this is the story of Show Me a Hero.

Warning: Spoilers Ahead

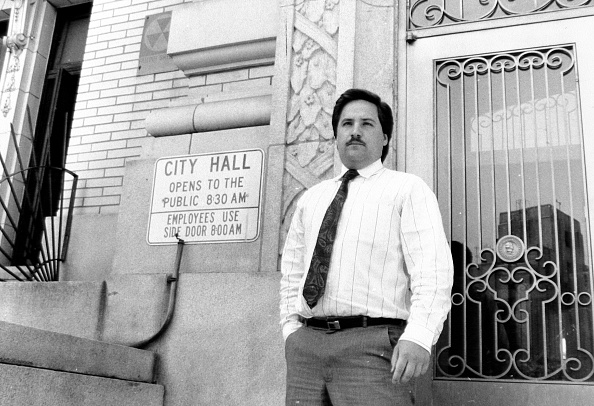

In 1987, at the age of 28, Nick Wasicsko became the youngest mayor in the nation at the time, and the youngest ever for the city of Yonkers. He was played exceptionally by Oscar Isaac, but this is what he looked like in real life.

Six years later after being elected to mayor, Nick Wasicsko drove to the cemetery where his father was buried, walked up to his gravestone, sat down, pulled out a gun, and shot himself. He left behind his wife, a clerk for the city of Yonkers.

What that has to do with public housing is a long and complicated story. In short, it began with the 1980 case, United States v. City of Yonkers. In that case, a federal court ordered that the city build 200 units of pubic housing and situate them in the white part of town as part of a desegregation effort to reverse the previous segregationist policies that placed 7,000 public housing units in a one-square mile radius of Yonkers.

The intolerant residents of the white areas didn’t want public housing near them. They argued that would cause property values to drop; they were afraid of crime, and they worried about a bad element in their neighborhoods.

They should have just called it what it was: Racism.

White people on the west side of Yonkers didn’t want poor black people in their areas, because they were bigots, because they were ignorant, and because they were selfish. For years, in fact, the white residents fought these public housing units, despite the fact that it was only 200 units in a city of nearly 200,000 people. That’s how afraid the white residents were of people with a different color of skin moving into their areas (it’s not highlighted in the miniseries, but in reality, the argument was as much about public housing as it was about additional black children attending mostly white schools).

With all of this as a backdrop, in 1987, Nick Wasicsko ran against Angelo R. Martinelli, a popular, six-term Republican, for mayor. Against all odds, Wasicsko won. At the time, the federal court had threatened the city of Yonkers with fines that could bankrupt the city in less than a month. Angelo Martinelli had essentially decided to acquiesce and let the construction of the public housing units begin. Wasicsko won because he promised the white citizens of Yonkers that he’d appeal the decision of the federal court.

After winning the election, however, Wasicsko lost the appeal, and he arrived at the same conclusion that his predecessor had: That he’d have to cave to the demands of the federal court, or else the city would not only go bankrupt, it would lose its fire department, its police officers, its trash collectors, etc. Despite concluding that allowing the housing units to go forward was in the best interests of the city, Wasicsko continued to face opposition from the city council, which — under the threat of fines and prison for contempt — refused to vote on a plan for where to build the houses. The councilmen who refused to comply were essentially appeasing their constituencies: angry white people who didn’t want black people living close to them.

It took a great deal of effort, a lot of lobbying, and threats from the federal courts, but Wasicsko was finally able to push a plan through. It would cost him re-election, however, as the man who defeated him in the next election in 1989, Henry Spallone, was the man who opposed him the hardest on the public housing issue. As mayor, Spallone would also learn that fighting against the public housing units was impossible, and after recognizing that there was no more battles to fight, Spallone would also lose his bid for reelection.Those housing units, however, were eventually built, but not without a few incidents of graffiti and vandalism. The residents from the east side of town did eventually move into new townhouses on the west side (and those units continue to exist today), but the battle that Wasicsko fought to get them erected had taken its toll. He’d lost popularity within the citizenry, and though he was given a runner-up citation for the 1991 John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award, Wasicsko barely managed to win a city council seat in his own district for another term. Subsequently, the mayor gerrymandered him out of a chance of winning his district in the next election, and he ended up losing in the 1993 Democratic primary.He took his life on election day in 1993. Why? Because of politics. Because the people within power sought to keep him out of power, and that included an investigation into an embezzling scheme with which he had nothing to do. He wasn’t even under official investigation, but the whiff of impropriety that encircled him was enough to further tarnish his reputation. His political career was essentially over, and Wasicsko apparently couldn’t bear the thought of being just another resident of Yonkers, not after all he’d done to further progress in the city.

It’s a heartbreaking story, less about a “hero” and more about a man who was forced into the position of one. As even his executive aide said after his death, “He wasn’t pro-desegregation, he was pro-compliance.” He did the unthinkable. He followed the law because he had no other choice. It would cost him his political career and ultimately, his life.

That’s just one half of the story, however. The other half involves the black residents who lived in crime-ridden, impoverished, dilapidated public housing on the east side of town. They just wanted a better life for themselves and for their families. It was the white people — who didn’t know or understand the black residents — that kept it from happening. In fact, it would take 27 years before the case was fully resolved. In 2007. It took nearly three decades of hostile litigation, millions in legal costs (and even more in human costs) and the near bankruptcy of Yonkers before those housing units were not only allowed to be built, but allowed to remain.

Don’t think for a minute, however, that the problem has been solved nationwide. There are still intense battles over desegregation all across the country in spite of the fact that studies show that, in schools at least, desegregation is the only proven way to close the achievement gap between white and black American students on standardized testing scores. In fact, an issue very much like the one that took place in Yonkers in the 1980s sprang up again in 2013, when a predominantly black school in Normandy, Missouri — where Michael Brown attended — failed, allowing 1,000 mostly black students to be bussed 45 minutes away into a predominantly white school in the suburbs. Those suburban parents, however, fought the very same fight that those in Yonkers fought 30 years before, with many of the same sentiments echoed: “It’s not about racism, it’s about property values, it’s about keeping their children safe and away from crime!” That account was covered in a recent episode of This American Life, and like Show Me a Hero, it did a masterful job of illustrating and humanizing the other side of the issue: The black students who simply wanted a chance at a better education and a better future.

At a human level, the battle in both Yonkers and Normandy, Missouri, can be reduced to the following opposing perspectives. During the Normandy desegregation crisis, there was a public school board hearing in the suburb where the black students would be bussed. During that hearing, the mostly white parents fought bitterly to block the black students from coming (and keep in mind that this was in 2013, not 1963). One parent suggested moving the school starting time to earlier in the day, making it more difficult for the black-out-of-town students to commute into their school. Hearing this, a black student from Normandy, Mah’ria Martin, who attended the school board hearing, tried to work up the nerve to speak in front of a hostile crowd.

Here are the words of a black high-school student (spoken through tears) as she relayed how she felt that day:

What if your kid was in Normandy High School, and they were just offered this opportunity, and other parents are saying, ‘we don’t want you here?’ How are you going to feel? Your kid is going to cry because parents are saying how awful your kid is when really they’re being put in the box, because they’re not like that. We’re just stuck there because we’re not open to the opportunities. And now we’re open to them, and now you want to be all mean, talking about you’re afraid of how big the class is going to be, the violence in the schools.

Unfortunately, she broke down before she could express herself in front of the crowd:

I had to walk out, go to the big gym, and we were standing by the door. Me and my mom were walking towards the aisle. And I had hesitated. I didn’t even get halfway to the microphone because of what the parents were saying.

I stopped the second to last row of chairs because I did not want to say anything anymore. And then this lady, I don’t remember who she was. She was like, I’ll hold your hand, because I kind of started to get a little teary-eyed. But I just couldn’t do it.

And what were those parents saying, exactly? Statements like these, spoken by a mother with cutting anger:

This is not a race issue. And I just want to say to– if she’s even still here, the first woman who came up here and cried that it was a race issue, I’m sorry. That’s her prejudice, calling me a racist because my skin is white, and I’m concerned about my children’s education and safety.

[CROWD APPLAUDS]

This is not a race issue. This is a commitment to education issue.

It’s a commitment to her child’s education, to the exclusion of Mah’ria Martin and others like her. That’s what she clearly meant, just as the white residents in Yonkers were committed to the safety and welfare of their neighborhoods, to the exclusion of the safety and welfare of the black neighborhoods.

It’s racism, but it’s also just plain selfishness. That selfishness, directly and indirectly, cost Nick Wasicsko his life, and that’s the story of Show Me a Hero.

(Via New York Times, HBO, This American Life)