In the wake of the 2016 election, a group of despairing Democrats in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, formed a new political group to ensure that they would never be out-organized locally again. Faith leaders, small-business owners, social workers, nonprofit leaders, teachers, and students joined together as part of the historic dusting-off that was taking place all across the country. The group, which came to call itself Lancaster Stands Up, put its energy toward defending the Affordable Care Act from its multiple assaults in Washington and fending off the tea party-dominated state legislature in Harrisburg.

The group’s town halls and protests began to draw eye-popping numbers of people and even attracted national attention. With their newfound confidence, Lancaster progressives looked toward local and federal elections. The national press was captivated by the upsets across the state of Virginia in November, but that same night in Pennsylvania, Democrats across the state in local elections knocked Republicans out of seats they’d owned forever. The surge suggested that capturing the congressional seat covering Lancaster and Reading, which Democrats lost by 11 points in 2016, was well within reach.

In June, one of their own, Jess King, who heads a nonprofit that helps struggling women start and run small businesses in the area, announced that she would be running to take out Republican Rep. Lloyd Smucker in Pennsylvania’s 16th District. Nick Martin, her field director and another co-founder of Lancaster Stands Up, was a leading activist in the popular and robust local anti-pipeline movement, an organized network King was able to tap into.

She planned to focus a populist-progressive campaign on canvassing and harnessing grassroots enthusiasm. If suburban Republicans came along, attracted by the promise of Medicare For All or tuition-free public college, then great, but they would not be King’s target.

Lancaster Stands Up voted to endorse King, as did a local immigrant rights group with a broad grassroots network, Make the Road PA. Justice Democrats, a small-dollar operation that was backing leftist Democrats, got behind her as well. (The primary is set for May 15, with the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruling on Monday that the GOP had illegally gerrymandered the state’s congressional districts, insisting they be redrawn before the primary. The decision could cut either way for King, depending on the shape of the new map.)

King then sought to secure the endorsement of the major players in Democratic Party circles. Her campaign reached out to EMILY’s List, which was founded to elect pro-choice women to Congress. EMILY’s List sent King a questionnaire, which she filled out and returned, affirming her strong support for reproductive freedom.

That was October, by which point her campaign had broken the $100,000 mark, a sign of viability she had hoped would show EMILY’s List that she was serious. “We followed up a few times after and did not hear back,” said King’s spokesperson, Guido Girgenti.

It turned out the Democratic Party had other ideas — or, at least, it had an old idea. As is happening in races across the country, party leaders in Washington and in the Pennsylvania district rallied, instead, around a candidate who, in 2016, had raised more money than a Democrat ever had in the district and suffered a humiliating loss anyway.

Christina Hartman, by the Democratic Party’s lights, did everything right during the last election cycle. She worked hard, racking up endorsements from one end of the district to the other. She followed the strategic advice of some of the most sagacious political hands in Pennsylvania, targeting suburban Republicans and independents who’d previously voted for candidates like Mitt Romney, but were now presumed gettable.

“For every one of those blue-collar Democrats [Donald Trump] picks up, he will lose to Hillary [Clinton] two socially moderate Republicans and independents in suburban Cleveland, suburban Columbus, suburban Cincinnati, suburban Philadelphia, suburban Pittsburgh, places like that,” Ed Rendell, the state’s former governor and titular leader of the state party, had predicted to the New York Times.

Hartman, with the energetic support of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and EMILY’s List, used her fundraising prowess to go heavy on television ads to drive her moderate message, confident that the well-funded Clinton ground game would bring her backers to the polls.

It did not.

Hartman was swamped by Smucker by 34,000 votes, badly underperforming even Clinton, who lost the district by about 21,000 votes. Trump and Smucker had indeed picked up some blue-collar Democrats, but not enough Republicans switched over to make up for the loss.

After spending $1.15 million in 2016, she had finished with 42.9 percent of the vote. In 2014, a terrible year for Democrats, a little-known Democrat spent just $152,000 to win almost the same share, 42.2 percent of the vote.

In July, Hartman announced she would make another run at it in 2018.

She quickly found the support of the state’s Democratic establishment, led by Rendell. “I’m proud to support her run for Congress in 2018. With her track record of success, we can count on Christina Hartman to show up for the people of PA-16 and to be part of the solution to end Washington gridlock,” Rendell said.

Along with Rendell came failed 2016 Senate candidate Katie McGinty; Attorney General Josh Shapiro; Auditor General Eugene DePasquale; Treasurer Joe Torsella; and Reps. Dwight Evans and Brendan Boyle of Philadelphia, and Matt Cartwright from Lackawanna, who politely dubbed her 2016 run “notable” in the campaign press release.

The simultaneous announcement of endorsements from the top elected officials in the party is a way to send a signal that the party has chosen its candidate. Another signal came in September, when Rep. Joe Crowley of New York, the House Democratic Caucus chair, gave money to Hartman through his leadership PAC. EMILY’s List followed suit, endorsing Hartman in December without extending a courtesy call to King’s campaign, Girgenti said.

“The fact that so many women are running is a good problem to have,” EMILY’s List’s spokesperson Julie McClain Downey told The Intercept. “Our goal as an organization is to help our candidates win and ultimately get more pro-choice Democratic women elected — sometimes that requires tough decisions. But we could not be more thrilled to see many women stepping up to run for office, and we hope to work with them for years to come.”

The decision stung, King said. “I’ve consistently supported full funding for women’s health, including contraception, and safe abortion as a last resort. I’m the only candidate running on Medicare For All and debt-free public college, policies that would hugely benefit women and working moms who struggle to make ends meet as insurance premiums and college tuition go up.”

In mid-October, the DCCC hosted a candidate week in Washington, bringing in Democrats running for the House from around the country for trainings and networking. Hartman was invited; King was not. As part of the candidate gathering, an off-the-record happy hour with national reporters was hosted by the Democratic National Committee in its “Wasserman Room.”

Resisting the Resistance

In his farewell address, President Barack Obama had some practical advice for those frustrated by his successor. “If you’re disappointed by your elected officials, grab a clipboard, get some signatures, and run for office yourself,” Obama implored.

Yet across the country, the DCCC, its allied groups, or leaders within the Democratic Party are working hard against some of these new candidates for Congress, publicly backing their more established opponents, according to interviews with more than 50 candidates, party operatives, and members of Congress. Winning the support of Washington heavyweights, including the DCCC — implicit or explicit — is critical for endorsements back home and a boost to fundraising. In general, it can give a candidate a tremendous advantage over opponents in a Democratic primary.

Prioritizing fundraising, as Democratic Party officials do, has a feedback effect that creates lawmakers who are further and further removed from the people they are elected to represent.

In district after district, the national party is throwing its weight behind candidates who are out of step with the national mood. The DCCC — known as “the D-trip” in Washington — has officially named 18 candidates as part of its “Red to Blue” program. (A D-trip spokesperson cautioned that a red-to-blue designation is not an official endorsement, but functions that way in practice. Program designees get exclusive financial and strategy resources from the party.) In many of those districts, there is at least one progressive challenger the party is working to elbow aside, some more viable than others. Outside of those 18, the party is coalescing in less formal ways around a chosen candidate — such as in the case of Pennsylvania’s Hartman — even if the DCCC itself is not publicly endorsing.

It’s happening despite a very real shift going on inside the party’s establishment, as it increasingly recognizes the value of small-dollar donors and grassroots networks. “In assessing the strength of candidates for Congress this cycle, we have put a greater premium on their grassroots engagement and local support, recognizing the power and energy of our allies on the ground,” said DCCC Communications Director Meredith Kelly. “A deep and early connection to people in the district is always essential to winning, but it’s more important than ever at this moment in our history.” The committee, meanwhile, has made major investments in grassroots organizing, field work and candidate training, which also represents a genuine change.

But change is hard, and it isn’t happening fast enough for candidates like King. So a constellation of outside progressive groups — some new to this cycle, some legacies of the last decade’s growth in online organizing — are stepping in, seeing explosive fundraising gains while the Democratic National Committee falls further and further behind. The time between now and July, by which most states will have held primaries, will be among the most important six months for the future of the Democratic Party, as the contests will decide what kind of party heads into the midterms in November 2018. The outcome will also shape the Democratic strategy for 2020, which in turn will shape the party’s agenda when and if it does reclaim power.

“We are proud to work with women, veterans, local job creators, and first-time candidates in their runs for Congress, whose records of service to our country and communities are being recognized – first and foremost – in the districts they aim to serve,” Kelly said.

In an era of regular wave elections — 2006, 2008, 2010, and onward — sustainable majorities may be elusive. The smartest play for the party that takes power, said Michael Podhorzer, political director for the labor federation AFL-CIO, is to seize the opportunity when a wave washes it into power, implement an aggressive agenda, and then defend it from the minority when the party is inevitably washed back out — much as Democrats did successfully with the Affordable Care Act, and as Republicans hope to do with tax cuts. It’s a strategy that means moving two or three steps forward and holding as many of those gains until power is reclaimed, then moving another two steps forward. But it’s only possible with candidates-turned-lawmakers ready to take bold action when they have the chance.

Prioritizing fundraising, as Democratic Party officials do, has a feedback effect that creates lawmakers who are further and further removed from the people they are elected to represent. In 2013, the DCCC offered a startling presentation for incoming lawmakers, telling them they would be expected to immediately begin four hours of “call time” every day they were in Washington. That’s time spent dialing for dollars from high-end donors.

Spending that much time on the phone with the same class of people can unconsciously influence thinking. There is, former Rep. Tom Perriello, D-Va. said in a 2013 interview, “an enormous anti-populist element, particularly for Dems, who are most likely to be hearing from people who can write at least a $500 check. They may be liberal, quite liberal, in fact, but are also more likely to consider the deficit a bigger crisis than the lack of jobs.”

Perriello was elected in the 2008 Obama wave and washed back out in the tea party one that followed. The time spent fundraising, he said in 2013, “helps to explain why many from very safe Dem districts who might otherwise be pushing the conversation to the left, or at least willing to be the first to take tough votes, do not – because they get their leadership positions by raising from the same donors noted above.”

Stephen Lynch, a House Democrat from Massachusetts, was elected in 2000 after a competitive primary. In 2013, he ran and lost a Senate special election against Ed Markey, with the party squarely behind Markey. “It’s challenging,” he said. “There were leaders in the Democratic Party that were discouraging people from donating to me.”

Lynch now faces a primary challenge from Brianna Wu, an engineer famous for taking on the “alt-right” in the GamerGate affair. In general, he said, the party should stay neutral.

“You’d rather have an election than a selection. Sometimes it actually makes our candidates stronger to have competition. I understand the parties are more concerned with the resources spent in the primary. Obviously if you have an uncontested primary, you save a lot of money, but I think from a leadership standpoint — small “l” leadership — you might develop a better candidate if they have a challenger early on.”

If money isn’t necessarily the best path to victory, that smart Washington-based operatives continue to make it the key variable regardless raises the question of what other motivations may be in play. For Lynch, the answer is simple: It’s a racket. “The Democratic and Republican parties are commercial enterprises and they’re very much interested in their own survival,” Lynch said. “The money race is probably more important to them than the issues race in some cases.”

The Intercept asked Lynch if the commercialization he referred to was for the benefit of the officials working in and around elections. “How much of the focus on fundraising,” we asked, “has to do with pumping money into this ecosystem of consultants and everybody else?”

“That’s what I mean,” Lynch said. “It’s a commercial enterprise.”

How Much Money Can You Raise?

The way to win party support is to pass the phone test.

In order to establish whether a person is worthy of official backing, DCCC operatives will “rolodex” a candidate, according to a source familiar with the procedure. On the most basic level, it involves candidates being asked to pull out their smartphones, scroll through their contacts lists, and add up the amount of money their contacts could raise or contribute to their campaigns. If the candidates’ contacts aren’t good for at least $250,000, or in some cases much more, they fail the test, and party support goes elsewhere.

Asked about the process, Kelly, the DCCC communications director, said, “Our support for a candidate is not based on the amount of money that their personal network can raise – in fact there are many strong candidates that we support with a limited ability to raise money from people that they know.”

That emphasis on fundraising can lead the party to make the kinds of decisions that leave ground-level activists furious. Take, for example, the case of Angie Craig, a medical device executive who ran for Congress in Minnesota’s second district in 2016 and has thrown her hat in the ring again.

The medical device industry is huge in Minnesota, and its outsized lobbying power is felt acutely in Washington. Despite spending $4.8 million, Craig lost by 2 points. That narrow defeat, though, belied the true failure of her campaign. She was, objectively, the least inspiring candidate up and down the ballot: Craig underperformed Clinton by 4,000 votes and even underperformed Democratic state Senate and House candidates by 13,000 and 2,000 votes, respectively. In 2012, the previous presidential cycle, congressional candidate Mike Obermueller spent $710,000 for a nearly identical level of support.

Jeff Erdmann thinks he knows why Craig lost. He was a volunteer for her in 2016, phone banking and going door to door. That spring, a voter asked him a question about Craig’s position on an issue that he couldn’t answer, so when Craig held a Q&A with the volunteers, he asked her if it was OK to direct voters to the website for an answer. “No, not really,” Erdmann recalled her saying, “because we haven’t developed our website yet because we don’t want the Republicans to know where we stand, and we haven’t seen end-of-summer polling yet.”

Later, he said, he was phone banking and asked a supervisor what message he should tailor to the rural part of the district, since the script seemed aimed at city dwellers. “Just tell them the trailer-court story, they’re not big thinkers out there,” he said he was told, referring to Craig’s childhood in a trailer home.

This time around, Erdmann decided to run himself, and he has the backing of the People’s House Project, a group founded by former congressional candidate Krystal Ball to back working-class candidates. Michael Rosenow, Erdmann’s campaign manager, said he and Erdmann reached out to the D-trip but had a hard time getting through. When they learned about a gathering the organization was hosting at an adjacent congressional district, they decided to crash it.

Erdmann has the kind of charisma you’d expect from someone who has coached high school football — and has had remarkable success in that role for more than two decades in a state that cares deeply about the sport. He has also taught American government for 27 years, but all of that had not prepared him for the conversation he was about to have with Molly Ritner, the midwest political director for the DCCC, at a hotel bar in Minneapolis called Jacques.

“It’s been weird for Jeff,” said Rosenow, who was there for the July 10 meeting. “The first question out of her mouth was, ‘How much will you raise?’”

They had raised $30,000 by that point, a figure that Ritner deemed unimpressive. (By the end of December, the campaign had raised around $115,000, according to Rosenow.)

“That’s not very much,” Rosenow recalls Ritner saying. “Really all we care about is, the more money you raise, the more you can get your message out.”

Erdmann tried to jump in, beginning to lay out his backstory, hoping to make the case that getting your message out doesn’t matter if voters don’t like the message. “He seems like he was grown in the tank for this district, but they didn’t care at all,” Rosenow said, “All she wanted to know was how much money he could raise.”

Ritner had been Midwest fundraising director at the DCCC in 2013 and 2014, before taking a break to run the campaign of the Democrat who lost the Vermont governor’s race to a Republican in 2016. She noted that Craig had ran an “amazing campaign” last cycle and asked if Erdmann had any big funders ready to get behind him. “Jeff laughed. He said, ‘I’ve been a teacher my whole life, how would I have big funders behind us?’” Rosenow recalled.

DCCC Chair Ben Ray Luján, a Democratic representative from New Mexico, was in his hotel room upstairs, Ritner told them, but he didn’t come down for the meeting.

Erdmann estimated the meeting lasted eight minutes. “She ordered a pop, got it, drank it, threw the number out that we had to hit, and left,” he said. On her way out, Ritner put $2 on the table. The check came to $2.26, before the tip. “I looked at Mike and said, ‘That is why the Democrats lose,’” concluded Erdmann.

Asked about the Craig endorsement and the meeting with Ritner, a DCCC official noted that Craig, in addition to national party support, has important endorsements from local unions and others in the district, and that Erdmann never requested that Luján be in the meeting with Ritner.

In order to run, Erdmann has taken reduced pay for a shrunken course load to give him time to campaign. His wife, a speech pathologist, has taken on a second job so they can continue to pay bills.

“They don’t want to talk about the civil war in the party, but when you treat us like hill people when we come up here, what do you expect?” concluded Rosenow.

Craig, fresh off her “amazing” 2016 race, is back again. Ritner, according to Erdmann and Rosenow, said the DCCC would remain neutral in the primary, but that didn’t last long. In November, the DCCC endorsed Craig, joining EMILY’s List and End Citizens United, the trio of groups that represents the party’s central authority. Last week, she picked up the backing of the Congressional Progressive Caucus PAC.

Minnesota’s complicated, multi-round caucus system begins February 6, when delegates who will participate in the later caucus are chosen.

Bankrolled By a Campaign Finance Reform Group

End Citizens United, an ostensible political reform group, was founded in 2015 by three consultants from Mothership Strategies, all veterans of the DCCC. End Citizens United has since paid Mothership Strategies over $3.5 million in fees, according to Federal Election Commission records. In its first few years, other campaign finance reform groups grew suspicious of the PAC, which they referred to as a “churn and burn” group dedicated to raising money by blanketing email lists with aggressive solicitations, a hallmark of the DCCC’s own email strategy. That reputation began turning around the last two years, as the PAC began putting significant money into important races and working more collaboratively with other groups in the space.

But its pattern of endorsements remains closely aligned with the types of candidates backed by the DCCC, though End Citizens United is often far ahead the party. (In 2016, End Citizens United backed progressive Zephyr Teachout, while the DCCC lined up behind her opponent, one of the few instances of the two diverging.) The PAC’s entry into the Minnesota race is particularly odd, given that Craig, while at the medical device company St. Jude Medical, directed the firm’s political action committee in the 2012 election cycle, after spending the previous six years on its board. The goal of the PAC was to buy influence with Republican and Democratic leaders, as well as members of the tax-writing committees, in pursuit of repealing the medical device tax that was a key funding mechanism of the Affordable Care Act. The effort eventually met with significant success.

While she ran it, the PAC spent heavily on Republican politicians, directing funds in the 2012 cycle to Republican Sens. Mitch McConnell, Finance Committee Chair Orrin Hatch, Scott Brown, Mike Enzi, Richard Burr, Bob Corker, and John Barrasso. Then-Speaker John Boehner and presumed-future-speaker Kevin McCarthy, as well as the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, all got money from Craig’s PAC.

This, then, was the résumé that earned the support not just of the DCCC and EMILY’s List, but also of a group publicly committed to campaign finance reform. It’s as dissonant as the group’s support for Jason Crow in Colorado, a DCCC-backed candidate who works at a powerful law and lobbying firm.

A DCCC official, asked about Craig’s time running the corporate PAC, said it was unfair to accuse a married lesbian raising a family of being part of the political establishment, and that her business success was an asset, not a liability.

End Citizens United also stands by its endorsements of Craig and Crow. “Angie pledged to fight for reform, advocated for the public funding of elections, and ran a grassroots campaign with the support of many progressive organizations and local elected officials,” said End Citizens United’s Communications Director Adam Bozzi.

“Angie lost in 2016 by a narrow margin of 6,000 votes,” Bozzi added. “Unlike many House challengers in 2016, she was able to match the Democratic performance at the top of the ticket. Angie ran a strong campaign, in a tough district, in a difficult year for Democrats in Minnesota.”

“All Jeff talks about is political reform, so that was a shot to the heart,” said Rosenow, Erdmann’s campaign manager, on losing the endorsement. “If your goal is to get money out of politics, how in the fuck — I’m sorry, how in the hell are you backing someone who ran a corporate PAC?”

Why It Matters

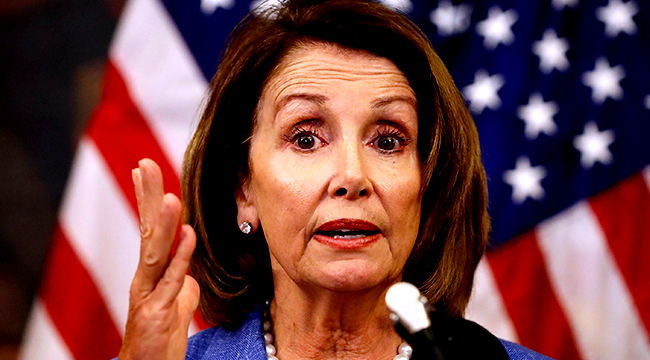

In Congress, one man or woman can be more than one vote. Leaders of both parties exploit the donor habits of major industries by sticking the newest and most vulnerable members on key committees like Financial Services or Ways and Means. Veteran members have come to call the new arrivals “the bottom two rows,” a reference to their junior position in the amphitheater-style committee rooms. Their voting habits are distinguished by the centrism they believe brought them to office. A simple majority is only as strong as its weakest member, and giving those weak members outsized power dilutes legislation. That’s what happened in the 2009-2010 session, as then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., who was in charge of the DCCC, as well as committee assignments, packed key panels with centrist and conservative freshmen and sophomores.

Those centrists were there not because the nation demanded moderation, but because Democrats had recruited them in 2006 and 2008 and put them there. Rahm Emanuel, Pelosi’s lieutenant who, at the time, ran the DCCC, looked for wealthy candidates who could self-fund a race. “The most important thing to the DCCC then was if you were self-funding,” said Michael Podhorzer of AFL-CIO. “That moved candidates toward business centrists and their ability to last after that election was not that great. And it set the stage for Obama’s Democratic majority not being as aligned with his policies as a more progressive majority might have.”

And those committees stacked with new centrists delivered weaker legislation than they otherwise might have. In 2009, Democrats dialed back their ambitions when it came to the size of the stimulus, the strength of Wall Street reform, and the quality and extent of coverage that would be provided by Obamacare — all in order to accommodate centrist members representing swing districts. Polls show that the ACA is not unpopular because it is too progressive; rather, its problem areas are the elements of it that are too conservative — high premiums and high deductibles.

The DCCC’s failure to understand the changing demographics of the electorate is costing the party. “There’s a big change happening since 2012 in who votes for Democrats and that the kind of profile that at least had conventional wisdom behind it — someone who is a self-funder, probably a lawyer or business person, older, has paid their dues in state legislatures — is wrong for the time, that nationally about half of all people who vote for Dems now are people of color and that is not always reflected, obviously, in who gets in office, and there are a lot of folks who sit it out because they’re not seeing candidates who seem to represent them,” Podhorzer said. “The candidates have to sort of catch up to where their constituencies are.”

Yet the types of candidates Emanuel wanted to bring to Washington in 2006 are the same ones today’s House campaign arm is working to get elected. Even if you agree with the ideological approach, said 2016 congressional candidate Zephyr Teachout, it’s a flawed strategy structurally. Last cycle, the DCCC worked against Teachout, a progressive activist and law professor, in her primary campaign in New York. She went on to win it by 40 points anyway, pulling in 2 points more than Hillary Clinton, but still lost the general election.

“Structurally, they’re going to be idiots because there’s no way they can bring in the talent to do it right,” she told The Intercept of the DCCC’s approach to picking candidates. “Their strategy is stupid in the first place and bad for democracy, but then it’s really stupid because they have 26-year-olds sitting around who don’t know anything about the real world deciding which candidates should win.”

Former Rep. Dan Maffei, who won House elections in Syracuse in 2008 and 2012, but lost in 2006 and 2010, said that Teachout is right — that the country is just too big, and politics too unpredictable. “In 2006, they didn’t come because they thought I had no chance. In 2010, I didn’t get much help from the DCCC or outside groups because they thought I would win fairly easily, and I barely lost. The DCCC isn’t really able to predict,” he said, noting that some members who did get massive support in 2010 lost by 30 points.

This time around, the DCCC doesn’t want a replay of the 2016 presidential primary, with a big, roiling debate over the party’s fundamental values swamping warmed-over talking points about party unity and opposition to the GOP. (“End Citizens United” is one such example of unifying and progressive-sounding but ultimately toothless rhetoric.) The D-trip’s solution, though, amounts to asking the candidates on the Bernie Sanders side of the equation to play nice. Specifically, the DCCC memorandum of understanding, obtained by the Young Turks, asks candidates to make the following pledges:

- The Candidate agrees to run a primary campaign that focuses on highlighting our shared values as Democrats and holding Republicans accountable.

- The Candidate agrees not to engage in tactics that do harm to our chances of winning a General Election. In addition, the Candidate agrees to hold a unity event with their primary opponents following the primary.

- The DCCC agrees to provide messaging and strategic guidance on holding the Republicans accountable and highlighting our shared values as Democrats.

Meet the Candidates

Fundamentally, what the DCCC’s phone test does is change the kind of person who can run and win, which then changes the kind of person who is representing the party to the public. Because the key variable that decides party support is fundraising, the DCCC’s decision-making is often ideological in its result, even if that was not the intent. By focusing on dollars, the party winds up with medical device executives, rather than American government teachers or football coaches.

In The Intercept’s review of a handful of primary races the party has gotten involved in, a few clear patterns emerged: There’s almost always an obvious political difference between the candidates the party backs and those it doesn’t, but in other areas — gender, race, sexual orientation, and professional background, for example — the congressional hopefuls on both sides of the divide are similarly diverse. Establishment Democrats of today are just as willing — or perhaps more so — to back a lesbian woman of color as they are a straight, white man, and the same is true on the left. In what is perhaps the crux of the issue, the Democratic Party machinery can effectively shut alternative candidates out before they can even get started. The party only supports viable candidates, but it has much to say about who can become viable.

Virginia District 2 — Karen Mallard is a public school-teacher in Virginia Beach, where she’s lived her entire life. Her story would be laughed out of a political novel as too on-the-nose if it weren’t real: When she learned that her father, a miner, didn’t know how to read, she set out to teach him and so, developed her passion for teaching. She formed her politics as a child standing on the picket line with her grandfather, also a miner. Trump’s election convinced her to become a first-time candidate, and she traveled to D.C. to drum up support, meeting with Danny Kedem at EMILY’s List. Kedem was fired up, Mallard said, and promised to arrange a meeting with his counterpart at the DCCC. But the meeting never happened because, Kedem later told her, the party had already settled on its man, Lynwood Lewis, When Lewis dropped out, the DCCC turned its attention to party leader Dave Belote, who ran briefly before dropping out after his mother fell ill. That still didn’t create an opening for Mallard, though. Two days after the stunning Virginia election, Elaine Luria, a Norfolk business owner and Navy veteran, called Mallard and told her she planned to get in. “This district is turning blue,” Mallard recalls Luria telling her. Mallard, relaying the conversation during an interview in December, said Luria told her that the DCCC had recruited her to run and would be supporting her after she announced in January. Sure enough, Luria announced her entry in January and was immediately endorsed by Lewis and Belote.

Mallard, however, thinks her experience in the community will pay off. “Everywhere I go, I see somebody I taught or coached. The DCCC needs to listen to people. Just because you can stroke a check for $100,000 doesn’t mean you’re the best candidate,” she said. “EMILY’s List gave me some consultants to hire, but I’m a public school teacher. I can’t afford to hire anybody.”

Nevada District 3 — Democrats and Republicans have battled for several cycles over this Henderson- and south Las Vegas-based seat. Susan Lee, an education advocate and the spouse of a wealthy casino executive, founded a homeless shelter and self-funded a failed bid for Congress for a different Nevada district in 2016. Now, despite a crowded field of several challengers, Lee is running in Nevada’s 3rd District with the support of DCCC and the backing of former Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid. Jack Love, a first-time candidate who announced his campaign before Lee did, said he contacted the state party office and never heard back. The DCCC, End Citizens United, and other party PACs, Love said, declined to interview him. “They basically anointed one person without even speaking with me,” said Love, whose platform includes progressive policy priorities like Medicare For All, though his campaign bank account includes precious little money. “It’s clear to me that the only thing that matters to the party is who’s got the money.”

Arizona District 2 — Last year, former Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick, a tough-on-immigration candidate who previously represented a northern Arizona district, bought a house to run for this Tucson-area seat. The DCCC, Emily’s List, End Citizens United, and other PACs coalesced quickly behind her campaign, ignoring a spirited challenge from former Assistant Secretary of the Army Mary Matiella. “A candidate’s viability is judged too quickly and too narrowly,” Matiella, who could be the first Latina to represent Arizona in Congress, told The Intercept. “The ability to immediately post a six-figure quarter isn’t just the primary consideration, it’s the only one. That kind of artificial barrier to political involvement is going to disenfranchise not only qualified candidates like myself, but thousands of new and optimistic voters the party should be engaging.” Matiella is backed by Justice Democrats, Democracy for America, and Project 100.

Kansas District 4 — In April, the political world turned bug-eye on Wichita, Kansas, as the results of a special election to replace Mike Pompeo came rolling in. For a tense stretch of time, it looked like James Thompson, running on a progressive platform that hewed closely to that of Sanders, might just pull off an upset in the heart of Koch Industries country. He wound up about 7,500 votes short, but immediately announced his plan to run for the same seat, this time against the Republican incumbent Ron Estes, in 2018. Washington Democrats were not particularly enthused about his chances. “I have never heard hide nor hair from the national party about the race,” Thompson said. His primary opponent, Laura Lombard, who moved back to the district from Washington, said she’s been in touch with the DCCC, but the party doesn’t like the odds of winning the district and isn’t helping in the primary.

Thompson is not clamoring for party support. “From what I’ve seen of the DCCC’s help, they want a bunch of promises made you’ll raise X amount of money, and you’ll spend this amount on TV ads.” he said. “At this point I’m not interested in having the DCCC, which has a proven losing record, try to come run my campaign.”

Nebraska District 2 — The Democratic Party has largely lined up behind former Rep. Brad Ashford to take back this Omaha-based seat. The DCCC and other PACs have provided resources and endorsements to Ashford, who compiled one of the most conservative voting records for any Democrat in the House during his time in office. Kara Eastman, another Democrat competing in the primary on a populist campaign of single payer and tuition-free college, said that, after inviting her to candidate week, the party has attempted to shut her out of the campaign. “Well, we have been in contact with people from the DCCC since we started the campaign, and I was told that they would be remaining neutral until after the primary, and now it’s clear that’s obviously not the case,” Eastman, who has raised more than $100,000, told The Intercept. Eastman is backed by Climate Hawks, at least three local unions, and some local party officials. The Progressive Change Campaign Committee, which was founded in 2009 as a small-dollar alternative to the DCCC, is leaning toward planning to endorse her. In 2017, the national Democratic groups shocked Nebraska Democrats by pulling support for mayoral candidate Heath Mello over his past votes for bills to ban abortions after 20 weeks and the requirement that an ultrasound is used on a woman seeking abortion. Ashford, as a state legislator, voted for the same two bills, while Eastman is running on a solidly pro-choice platform. But that hasn’t prevented national Democrats from rallying behind Ashford. Last year, DNC Chair Tom Perez, in the wake of the Mello controversy, drew a line in the sand, saying that “every Democrat, like every American, should support a woman’s right to make her own choices about her body and her health. That is not negotiable and should not change city by city or state by state.” But that hasn’t prevent national Democrats from rallying behind Ashford. An EMILY’s List spokesperson said the group is monitoring the race but has yet to weigh in.

California District 50 — Ammar Campa-Najjar had his moment in the viral sun earlier last year, as the internet celebrated the hotness of this congressional candidate. He has since won the backing of Justice Democrats and a slew of local labor and Democratic groups. His opponent Josh Butner has said that he was not recruited by the DCCC, but encouraged to run by “local Democrats.” The New Democrat Coalition PAC, the pro-Wall Street wing of House Democrats, has given him $5,000. Butner was cited in two articles about the party’s ability to recruit veterans; the DCCC made sure to alert reporters about the coverage, issuing a press release. “I don’t want to assume foul play from the party, but there have been people suggesting they’re tipping the scales,” said Campa-Najjar. He said that on January 27, when the district does its pre-endorsement voting, he hopes to win the votes of those delegates by a wide margin to send a message. “If the most highly active people have already made their decision, it’s only a matter of time until the national party does,” he said. “Is there a lot of conventional thinking that’s leaning toward the profile of Josh? Yeah, absolutely, but we live in very unconventional times where candidates like Danica [Roem] beat Bob Marshall.”

Iowa District 1 — George Ramsey, a 30-year Army veteran, would be the first African-American to represent this district, though he is, by his own definition, not the most progressive candidate in the race. That would be Courtney Rowe, a Medicare For All backer, who has the support of the Justice Democrats and is working to rally the progressive base. But Ramsey, who is not too far to her right, has also been shut out by the party. In July, as he began to set up his Iowa congressional campaign, he reached out to the DCCC’s regional director. “We talked about what their expectations would be for their support for candidates. They made it very clear that fundraising was one of the primary mechanisms for their support,” Ramsey said, then clarified that fundraising was actually alone as the top priority. “They didn’t really put a number, but for us it was very clear that they’re looking for general election-type of numbers and not necessarily the type of numbers a candidate would need to get through a primary. They were talking about numbers that end in millions.” The DCCC is backing state Rep. Abby Finkenauer, as is End Citizens United and EMILY’s List.

Colorado District 6 — This suburban seat has long been an elusive Democratic target. One candidate for the district, clean energy expert and entrepreneur Levi Tillemann, charged that Rep. Steny Hoyer, the No. 2 Democrat in the House, pressured him to get out of the race in favor of Jason Crow, a veteran and partner at powerhouse Colorado law and lobbying firm, who is backed by the DCCC, the local Democratic congressional delegation, and End Citizens United. In a response to an inquiry from The Intercept, Hoyer did not deny pressing Tillemann, and said that he is “proud to join countless Coloradans in supporting Jason Crow in Colorado’s 6th District.” Not all Democrats are on board with the party’s strategy, though. State Party Chair Morgan Carroll protested the DCCC’s support for Crow over Tillemann, writing on Facebook, “The DCCC verbally said they would be neutral and in practice just endorsed one of the candidates in CD6.” Tillemann comes from a long line of political heavyweights in Colorado and moved back to the state to run.

It Feels Like Déjà Vu

Democratic party officials are not, by nature, moved to deep reflection by election losses. They have a plan and they’re sticking to it. The bad news for grassroots activists is that the Democratic Party’s leaders cannot be reasoned with. But they can be beaten.

If Democratic leaders are getting the sense that 2018 could be a wave election much like 2006, it’s worth looking at the last time the party swept into the House. The DCCC that year was run by Rahm Emanuel, who institutionalized the practice of only endorsing candidates with a demonstrable ability to either fundraise or pay for their own campaigns. Democrats that year beat 22 Republican incumbents and picked up eight open seats that had previously been held by Republicans. Because winners write history, the strategy has become conventionally accepted as wisdom worth following. But taking a closer look at the races themselves suggests the DCCC was flying blind.

In New Hampshire, for instance, the DCCC backed state House minority leader Jim Craig over local activist Carol Shea-Porter, in a classic establishment-versus-grassroots campaign. The conventional wisdom suggested that Craig’s endorsements, his moderation, and his ability to fundraise were what was needed in the district. Instead, Shea-Porter took a firm stand against the war in Iraq and organized an army of foot soldiers on the ground. Vastly outspent, she smoked Craig by 19 points in the primary.

The DCCC, in its wisdom, wrote her off, declining to spend a dime on what they saw as a lost cause. She spent less than $300,000 and, on the back of progressive enthusiasm, won the general election. She is retiring in 2018.

In California, the DCCC backed Steve Filson, a conservative pilot, against Jerry McNerney, who Emanuel believed was hopelessly liberal. After McNerney beat him in the primary, a peeved Emanuel said the DCCC wouldn’t be helping him in the general. A coalition of environmental groups got behind him instead, and McNerney won anyway.

In upstate New York, Emanuel went with Judy Aydelott, a former Republican who was a tremendous fundraiser. She was crushed by environmentalist and musician John Hall, after which the DCCC shunned the race as unwinnable. Hall won.

Emanuel completely ignored Larry Kissell, running in North Carolina; with the help of netroots activists, he ended up losing after a recount by just 329 votes. In 2008, this time with DCCC support, he won by 10 points. Emanuel did the same with Dan Maffei, who lost in a recount by roughly 1,000 votes. With DCCC support the next cycle, he won in 2008.

It can be difficult for challengers to go up against the party because it is often hard to tell how or if the party is taking side

The post Candidates Who Signed Up To Battle Donald Trump Must Get Past The Democratic Party First appeared first on The Intercept.