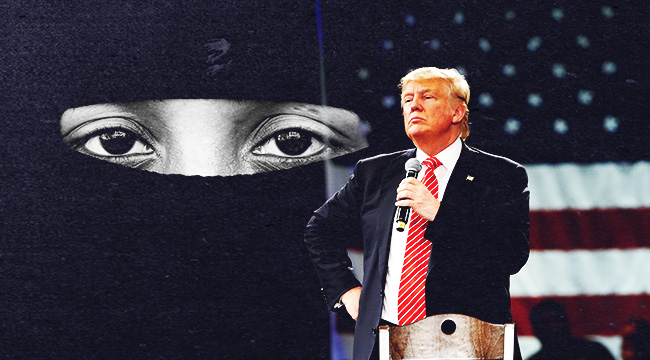

After a botched roll-out in January, President Donald Trump today signed a new version of his executive order to ban immigration to the United States from a number of Muslim-majority countries. The text of the new order removes Iraq from the list of countries affected and makes exceptions for green card holders and dual-citizens of targeted countries.

The order also removes exceptions for religious minorities, targeting en masse the citizens of Iran, Sudan, Yemen, Syria, Libya and Somalia. The travel ban will go into effect on March 16th, ten days from its signing. At a press conference announcing the revised order, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said the new measure will “bolster the security of the United States and her allies.”

The revised order represents an attempt by the Trump administration to escape the legal challenges that the first order generated when it was released this January. Described by some legal analysts as “a giant birthday present to the ACLU,” the original order was almost immediately tied up in the courts. It also generated widespread protests in the United States, as activists turned out to airports to demand the release of individuals being detained or denied entry to the country. A court in Seattle ultimately ruled that the ban was unconstitutional, terminating its applicability nationwide and fatally undermining attempts to turn it into law.

Despite a few modest revisions, there is little to indicate that the order signed today is different in intent. Trump’s own surrogates have publicly stated that it is intended to be effectively identical to the much-derided order signed in January. Steven Miller, a senior adviser to the president, described it as “the same, basic policy outcome for the country.” In a statement issued today the ACLU said that the revised order “shares the same fatal flaws” as the original one, adding that “the only way to actually fix the Muslim ban is not to have a Muslim ban.”

Despite the fact that Trump campaigned for the presidency on a promise of banning Muslims from the country, the administration has pushed back against claims that its executive order is discriminatory, describing it instead as a national security measure. But a Department of Homeland Security report leaked to the press last week threw cold water on that argument, saying that “citizenship is unlikely to be a reliable indicator of potential terrorist intent,” and finding that “few of the impacted countries have terrorist groups that threaten the West.”

A recent study by the Cato Institute has also found that people from countries targeted by the ban “have killed zero Americans in terrorist attacks on U.S. soil between 1975 and the end of 2015.” Legal advocates say the executive order has nothing to do with national security and is designed solely to prevent Muslims from entering the United States.

“This is still a Muslim ban, you don’t change the intent of an order simply by editing the language and re-releasing it,” said Abed Ayoub of the Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. “If you look at Trump’s own statements and the statements of his surrogates, it’s clear that this policy has been motivated from the beginning by anti-Muslim, anti-Arab and anti-immigrant sentiment.”

According to the text of the order, government agencies will now be mandated to collect data on immigrants to the United States who engage in gender-based violence like “honor killings” or who have been “radicalized after entry” into the country. This type of ethno-religious reporting on criminal activity has drawn criticism for being similar to policies pursued by xenophobic and authoritarian governments in the past.

The new order also puts draconian restrictions on U.S. refugee policy. Although the text of the revised order removes a specific ban on Syrian refugees, it freezes all refugee resettlement for 120 days and caps annual acceptance numbers at 50,000 per year, less than half the current figure. Immigration policy experts say these revisions will effectively ban many refugees from the United States, and not just Syrians.

“Changing the cap from the current 110,000 admissions to 50,000 is going to be extremely detrimental to not only Syrian refugees, but also other refugee populations suffering around the world,” said Kristie De Pena, immigration policy counsel at the Niskanen Center.

The international community is currently grappling with the largest refugee crisis since World War II and the U.S. decision to take a hard line against refugees is likely to impact the policies of other countries, too.

De Pena adds that the 120-day freeze on acceptances will have major negative consequences even if it is eventually lifted. Many refugees who have been approved for resettlement have received security clearances that will expire during the period of the ban, forcing them to start the process again from the beginning.

Ayoub of the ADC adds that his organization views the new order as part of a broader strategy by the administration to restrict access to the United States for immigrants, including but not exclusive to, Arabs and Muslims.

“It’s important that we keep the pressure and focus on this. Even though the words have changed the intent is the same,” Ayoub said. “This is all part of a larger anti-immigrant policy that we’re seeing from this administration. Just as it is important to keep in mind their intentions, it’s important to contest this measure as part of a larger strategy.”

The post Intent of Trump’s New Executive Order Is Basically Identical to His Original Muslim Ban appeared first on The Intercept.