Music + Culture

SHOWS

Covers Books

EVENTS

FEATURED

BRANDS

TRAVEL,

DRINKS & EATS

DRINKS & EATS

Latest

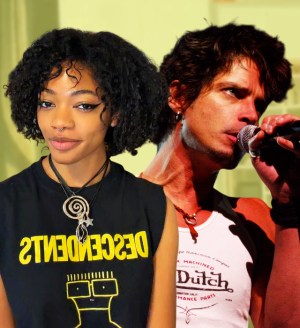

Uproxx’s Joypocalypse Breaks Down How Soundgarden’s Slow-Burning Grooves Make Them Distinct

Just a few months ago, Soundgarden achieved one of the highest honors in all of music with their induction into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. It all started in the '80s when Chris Cornell, Kim Thayil, and Hiro Yamamoto formed the band. There would be a handful of personnel changes, but in a few years, the group settled into its classic lineup of Cornell, Thayil, Ben Shepherd, and Matt Cameron. They became stars with the release of 1994's Superunknown, which features the group's signature song, "Black Hole Sun." After disbanding in 1997, they reformed in 2010, but called…

ASAP Rocky All But Confirms One Of His ‘Don’t Be Dumb’ Songs Disses Drake

At long last, after years of teasing and delays, ASAP Rocky has dropped his new album, Don't Be Dumb. Quickly, a standout track is "Stole Ya Flow," due to lyrics that seem to be dissing Drake. Relevant lyrics include, "First you stole my flow, so I stole yo' b*tch," in reference to Drake's rumored fling with Rocky's now-partner Rihanna, as well as, "n****s gettin' BBLs, lucky we don't body shame," a nod to Drake's supposed enhancement surgeries. Later, he references his former friendship with Drake and the rapper's son, saying, "First you was my bro, p*ssy n**** switched / Turned…

Mitski Follows A Standout 2025 By Announcing A New Album And Sharing The Single ‘Where’s My Phone?’

A few months ago, Mitski shared a terrific concert film. At the end of it, she teased a new album, indicating it was set for "the winter." Well, now we know more about that, as Mitski just announced Nothing's About To Happen To Me is set for February 27 via Dead Oceans. Today (January 16), she also shared a new single, "Where's My Phone," and an accompanying video. The song is a fuzzed-out rocker, and in the video, Mitski plays a recluse in a house full of clutter. Mitski hasn't given many interviews lately, but she did have a chat…

Days Before Release, ASAP Rocky Reveals The ‘Don’t Be Dumb’ Features And Tracklist

At last, Don't Be Dumb is finally coming: ASAP Rocky's long-awaited album is set to drop tomorrow, January 16. As the days remaining turn into hours, Rocky has pulled back the curtain by revealing the tracklist. He also shared the list of features (but not who appears on what track). The lineup is an eclectic mix, featuring Tyler, The Creator; Westside Gunn; Doechii; Brent Faiyaz; Thundercat; Gorillaz; BossMan Dlow; will.i.am; Danny Elfman; Jon Batiste; Slay Squad, and Jessica Pratt. Meanwhile, in a recent interview, Rocky spoke about how his mother wanted him to start a relationship with Rihanna, saying, "My…

Harry Styles Finally Announces His First Album In Four Years, ‘Kiss All The Time. Disco, Occasionally.’

Harry Styles has been at at a wedding in Paris, the Vatican, and Japan lately, among other places. Those "other places" apparently include the studio: Today (January 15), Styles announced a new album, Kiss All The Time. Disco, Occasionally.. The project is set to drop on March 6. The only other info we have about it at the moment is that it has 12 tracks and was produced by Kid Harpoon. Styles shared the cover art as well. The last the public saw of Styles in a major way was on the Love On Tour that ended in 2023. When…

The BTS Comeback Ramps Up As The Group Reveals The Title And Release Date Of Their New Album

BTS have been gradually rolling out their return this month. First, they teased an album and a tour. Then, they announced the tour dates. Now, it's album time, as today (January 15), the group announced Arirang, which is set for March 20. BigHit's website says of the album: "BTS The 5th Album, 'ARIRANG' holds special significance as it marks the first album released by the group in three years and nine months and sets out the the direction the members will take moving forward. The members were deeply involved throughout the songwriting and production process, infusing their own thoughts and…

Gracie Abrams Is Set To Make Her Acting Debut In A New A24 Movie

Gracie Abrams has Hollywood in her blood, as her dad is J.J. Abrams, one of the most acclaimed and successful filmmakers of the past few decades. Gracie herself hasn't gotten into acting in a major way, though... until now. Per The Hollywood Reporter, Abrams will make her acting debut in Please, a new A24 movie from Babygirl director Halina Reijn. Not much is known about the film, but The Hollywood Reporter notes that per sources, it's "a period female drama and will be a continuation of the edgy romance genre that Reijn tackled with Babygirl." In an Elle interview from…

Blackpink’s Long-Awaited Comeback Project Has A New Release Date And It’s Soon

Last summer, YG Entertainment founder Yang Hyun Suk said that Blackpink were shooting to have a new project out by the end of the year. He said at the time, "A lot of fans are curious about Blackpink’s album. I know that the Blackpink members and producers in charge of them are working very hard preparing the album. I’m hoping for Blackpink’s album to be out by November, at the latest. That’s what I’m pushing for – we’ll do our best to get Blackpink’s album out soon.” Well, they tried, but ultimately, it wasn't out by November, or the end…

Rolling Loud Is Doing Just One US Festival This Year, Led By Playboi Carti, Don Toliver, And NBA YoungBoy

Last week, Rolling Loud made a big announcement: They're doing just one US festival this year, and it's going down at Orlando's Camping World Stadium from May 8 to 10. Now, the other shoe has dropped, as today (January 14), they revealed the lineup. Headlining are Don Toliver, Playboi Carti, and NBA YoungBoy. Also playing are Chief Keef, Destroy Lonely, Sexyy Red, EsDeeKid, FakeMink, Nettspend, BossMan Dlow, OsamaSon, Homixide Gang, PlaqueBoyMax, SkaiWater, TiaCorine, Lazer Dim 700, and others. Tickets are available now on the festival website. In a statement, Rolling Loud co-founder Matt Zingler says: "Rolling Loud 2026 represents a…

Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea Announces His Debut Solo Album With A Thom Yorke Collaboration

While Flea is best known for his decades with Red Hot Chili Peppers, he routinely keeps himself busy outside of the band. Sometimes it's with acting, sometimes it's with supergroups like Atoms For Peace. It may be surprising, then, that he never released a solo album... but that's about to change soon. Today (January 14), Flea announced Honora, his first-ever solo album. It's set to drop on March 27 and it focuses on jazz and Flea's trumpet. He was joined by a venerable crew of jazz musicians: producer and saxophonist Josh Johnson, guitarist Jeff Parker, bassist Anna Butterss, and drummer…

The ‘Stranger Things’ Finale Highlights How Brands Should Prepare For Viral Moments

As people's experiences with pop culture continue to get more and more splintered, it may feel like it's harder for a moment to really break through on a broad level. But, mass attention moments still happen, most notably with the recent Stranger Things series finale. The show has become known for highlighting classic hits and the pattern after the fact is typically the same from the music world's perspective: Artists and songs featured on the soundtrack surge overnight, discovery among Gen Z listeners spikes, and there's sustained engagement across social media and streaming (YouTube, in particular). In a matter of…

BTS Just Announced A Year-Long Comeback Tour Launching Very Soon

Earlier this month, BTS gave their fans some long-awaited news: After years away fulling military service obligations in South Korea, the group is coming back with an album and a tour in 2026. Details provided at the time were sparse, but now the BTS has announced tour dates for this year and next. It kicks off in South Korea and Japan before making its way to North America in April. Venues for a lot of the shows are listed as "TBD," but the North American ones are all revealed now. Among the highlights are four nights at Los Angeles' SoFi…

Mary J. Blige Is Sharing ‘My Life, My Story’ In A New Las Vegas Residency Launching Soon

In recent years, Las Vegas residencies have become increasingly popular among artists at various points in their careers. After all, it's like a tour minus all that pesky traveling. Plus, being in the same venue for every show can make it easier to keep the production consistent. Now, Mary J. Blige is getting in on the action, as yesterday (January 12), she announced Mary J. Blige: My Life, My Story The Las Vegas Residency. She says in a statement: “I’ve been so excited to announce this Vegas residency. Creating a show like this has been something I’ve always wanted to…

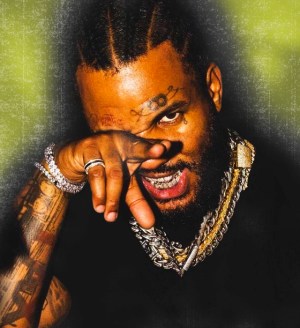

The Game Returns With Legendary Energy

The Game has never chased moments -- he's created movements. For more than two decades, the Compton rapper has treated hip-hop as an album-driven art form, rooted in authenticity, lineage, and lived experience. With Every Movie Needs A Trailer, a Gangsta Grillz collaboration alongside acclaimed producers Mike & Keys and mixtape king DJ Drama, Game isn't teasing nostalgia -- he's setting the stage for what comes next. Soulful but sharp, reflective yet defiant, the project feels like a veteran artist locking back into purpose. Thankfully, I gave The Game a few magazine covers back in the day, so he was…

Harry Styles Is Teasing Something As Fans Wait For A New Album

The last time we got a new Harry Styles album was in 2022 with Harry's House. Since that and the supporting Love On Tour, Styles has largely remained out the public eye (aside from random sightings like Pope Leo's introduction at the Vatican and marathons in Japan and Germany). Before 2025 came to an end, he unexpectedly shared a video from the aforementioned tour, sparking hope that Styles was generating attention for a reason. Mysteriously, Styles does appear to be teasing something on the way. Some promotional posters have been spotted around the world, with differing messages like "see you…

ASAP Rocky Unveils His Chaotic And Impressive New ‘Helicopter’ Video

It has been a long time coming for ASAP Rocky's new album Don't Be Dumb. It was supposedly finished in 2022. Then there was delay after delay after delay. Finally, though, it's coming: The project is set to drop this Friday, January 16. That's just days away, but before the release, Rocky has hyped it up today (January 12) with a new song, "Helicopter," and a video for the track. The video is a winner, a rapid-fire and surreal look at various scenes during a riot. Throughout, Rocky raps the song as he practices boxing, flies in a helicopter, and…

Sombr Turns In A Powerful Piano Cover Of Phoebe Bridgers’ ‘Motion Sickness’

After emerging as one of 2025's biggest breakout stars, Sombr's 2026 is off to a good start. Over the weekend, he dropped by BBC Radio 1 for a "Piano Sessions" performance. For his song, he, joined by a pianist, decided to sing a stirring rendition of Phoebe Bridgers' "Motion Sickness." It wasn't a surprising selection, as Sombr is a big Bridgers fan. In a recent interview, Sombr was asked about his favorite artists and he said, "Radiohead, Phoebe Bridgers, Bon Iver, The 1975, and obviously Sombr." He later said during the same chat, "I hope to collab with other artists…

Zach Bryan Unveils ‘Plastic Cigarette’ And Teases An Acoustic Version Of His New Album ‘With Heaven On Top’

Zach Bryan is at the start of a big year. In March, he launches a tour that will keep him sporadically busy until October. His new album With Heaven On Top is also set to drop tomorrow (January 10). Ahead of that, we have "Plastic Cigarette," what will presumably be the final taste of the album before its release. In an Instagram post from today, Bryan wrote of the album: "'With Heaven on Top' is a collection of songs my band and me recorded across three different houses in Oklahoma this winter. The cool air kept us all inside staggering…

GALE Takes Her Next Hit On The Road With Toyota In ‘The Sonic Route’

What does Latin pop music’s biggest breakout do when she’s just mixed her next hit, and she can’t wait to share it with her biggest fans? She takes it on the road… literally. The Sonic Route, UPROXX’s new team up with Toyota, follows Latin GRAMMY winner GALE as she cruises around Los Angeles, planning an exclusive surprise performance of her newest track, “Mi Tienes.” To pull it off, she's going to need the right team and the right car, utilizing the 2026 Toyota Corolla Cross Hybrid XSE as a rolling hub and showing that a good ride with your team…

Bruno Mars Is Finally Back With The Funky And Groovy New Single ‘I Just Might’

It's happening: This week, Bruno Mars announced a new album, The Romantic, and a big tour for 2026. At the time, he promised new music would arrive today (January 9), and now it has as Mars shares the video for "I Just Might." It's a classic Mars number: Catchy and carried by a throwback funky and soulful vibe. He also has fun in the video, featuring a bunch of different versions of himself dancing and playing the song. On his upcoming tour, he'll be joined by Silk Sonic partner Anderson .Paak (as DJ Pee .Wee), Leon Thomas, Victoria Monét, and…

Twenty One Pilots Captured Their Massive Mexico City Concert For An IMAX Concert Film, ‘More Than We Ever Imagined’

We are approaching 20 years of Twenty One Pilots and the duo remains huge: Their 2025 album Breach went No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart, making it their second chart-topper and fifth to peak at at least No. 3. The band remains a touring force, too, as they showed on The Clancy World Tour last year. They decided to capture their Mexico City performance, in front of 65,000 fans, for More Than We Ever Imagined, a new IMAX concert film. It's set to hit IMAX cinemas worldwide for a limited time starting February 26, with exclusive previews starting February…

El Malilla Is Putting Reggaeton Mexa On The Map

The reggaeton Mexa revolution is upon us and El Malilla (real name: Fernando Hernández Flores) is leading the charge while also making his mark as a multi-hyphenate. "I'm in the best moment of my career," El Malilla tells UPROXX while discussing his the upward trajectory of his music career and his experiences branching out as an actor, model, and entrepreneur. "I'm having fun doing concerts and going to the studio to make music. I believe when a person starts achieving fame, they can lose sight of who they once were. I'm happy, excited, and grateful because I've found the perfect…

Olivia Rodrigo Recruits David Byrne To Cover ‘Drivers License,’ Marking Five Years Of The Iconic Hit

Today (January 8) is the five-year anniversary of Olivia Rodrigo's "Drivers License," which went on to hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and launch Rodrigo's career as one of music's biggest stars. The tune ultimately led to a lot of fantastic opportunities for Rodrigo, including performing with David Byrne at Governors Ball last year. Now Byrne is helping Rodrigo celebrate half a decade of her breakout hit by performing the song himself, in a new cover shared today. Byrne, naturally, puts an alternative spin on the track, making it less of a powerhouse piano ballad but maintaining…

Bruno Mars Will Grace 2026 With His New Album ‘The Romantic’ And A Tour With Awesome Guests

We are officially entering Bruno Mars season. This week, he declared that a new album is coming. Now, we know more about it: Yesterday (January 8), Mars revealed the project is called The Romantic and it's set to drop on February 27. He also said new music is coming tomorrow, January 9. On top of that, he also has a massive tour lined up between April and October. His Silk Sonic partner Anderson .Paak will be joining on all dates (as DJ Pee .Wee), while Leon Thomas, Victoria Monét, and Raye will also perform at select dates. For tickets, there's…

Chris Patrick Isn’t Praying For A Moment — He Became One

Hip-hop still lives for moments. Damn the trends. Screw the metrics. Moments -- the kind you feel in your chest. In 2025, one of the most undeniable moments came from Chris Patrick, whose Kai Cenat freestyle didn't just go viral -- it cut through. It reminded rap fans why bars still matter, why intent still matters, why hunger is still the most powerful currency in rap. What followed wasn't just a spike -- it was a pivot: a Def Jam deal, a JID tour, and Pray 4 Me, a raw, real-time EP that documents faith, fear, grief, patience, and purpose.…