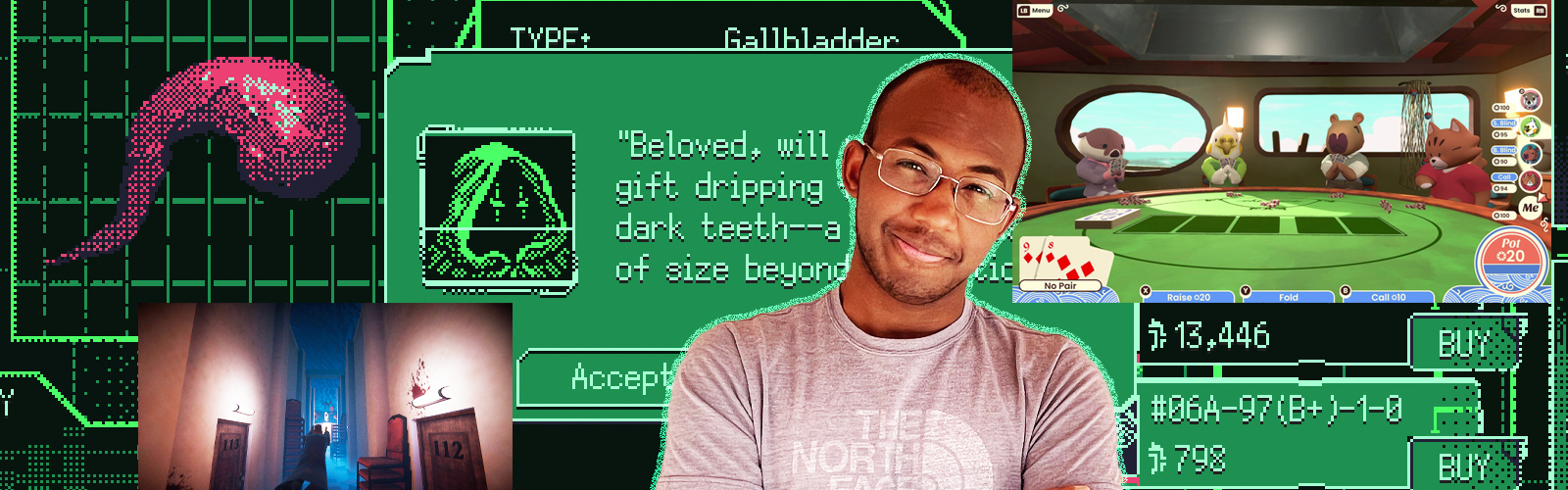

Xalavier Nelson Jr. (Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator, An Airport for Aliens Currently Run by Dogs) has thought a lot about how to make game development more sustainable.

Growing up in a military family meant Xalavier traveled around the world depending on where his family was needed. It exposed him to a wide array of experiences that influenced his exuberant personality and unique eye for creating weird, personal worlds in his games. Additionally, Xalavier became accustomed to creating deep friendships with people over the internet, something that would later help him create his indie game studio, Strange Scaffold, where he collaborates with fellow creatives from around the world to make uniquely weird games.

Like many people working in games today, Xalavier found his way into the games industry by being a games journalist first. At the age of 12, he began reviewing games for various outlets, though he jokes that some may have thought he was older than he was. Through his experience as a journalist, he met a variety of people in game development, and he himself started working with others to make small indie titles.

He’s learned a lot from his varied experiences, but the topic that keeps him up at night is how the games industry isn’t set up for sustainability when it comes to developing the games we love. Many studios spend months “crunching” (or working long hours to meet deadlines) and even more so, many creators end up leaving the industry altogether after spending years working on titles that never saw the light of day.

Xalavier believes there is a better, more sustainable way to make games. One that emphasizes the lived experiences of the people making them. He has worked to make Strange Scaffold a welcoming, collaborative studio, where people have more creative autonomy to make games in a more healthy way.

Uproxx spoke with Xalavier recently to talk to him about sustainability in the games industry. In the wake of countless examples of burnout, layoffs, and crunch, I was curious to examine how his studio, Strange Scaffold, is attempting something wildly different.

Strange Scaffold describes itself as a weird, sustainable game studio. What does sustainability mean for what you all are building?

There are a lot of different vectors for discussing sustainability. Personally, I believe sustainability is founded upon the idea of building machines, systems, and processes, that organize and support the needs of the people who make the games we love. We work in an industry that is built around things like ‘systems design.’ ‘How is the player impacted by this combination of abstract meters and numbers on a screen?’ But within the medium, there’s very little discussion of how we’re creating those systems for ourselves.

Strange Scaffold is my effort to put into the world an example of how, right now, the technology and the systems of distribution available to us let us build unique systems for supporting our goals and needs as individuals. I want to create systems within how me and my collaborators work that uniquely satisfy who we are as creators, and nurture people who join us in our endeavor for however long we work with each other.

That’s interesting, and I think an aspect to thread into this conversation about sustainability in game development is crunch and overwork.

I love that you brought up crunch because I talk to a lot of students and early-stage game developers these days. Almost always, the first questions that come up are about if a studio has crunch. To me, this is a bit of an indictment of the secrecy around game development processes, including the many factors that result in burnout. At Strange Scaffold, we consider crunch to be the beginning of a much larger conversation.

I’ve worked on projects where I was doing 60-hour weeks and felt fulfilled and able to live a good life mentally and physically. I’ve also worked on projects where I was part-time working 5-10 hours–and nearly left the games industry altogether. I’m attempting to use my experience and the collective knowledge of others to unpack the factors alongside crunch that assist in burnout.

Between those two examples, what do you think that says about the state of the industry right now in relation to crunch?

A big factor I’ve seen is the cancellation of games and, in turn, the inability to show the work you’ve done on those projects publicly. I’ve known people who have worked in the industry for over 20 years and have one shipped project to their name because of these practices. So as a principle, Strange Scaffold hasn’t canceled a single game. The human impact of knowing that your best work is trapped behind a lead box is not just heartbreaking, it’s disrespectful to the time, energy, and human effort that is represented by a canceled project.

Another thing that Strange Scaffold actively thinks about and plans around is the space that we occupy inside the lives of our collaborators. We intentionally design production pipelines that can move around the fact that you have a huge upcoming deadline in your day job or a thing that is going to burden you as a human being. I don’t particularly care how much money a Strange Scaffold game makes, as much as I would love for every project to continue to be profitable and sustainable for the studio. Whether a title sells 100 copies or 1 million, I care most that our processes are human-centric and continually refined.

There’s nothing more heartbreaking than looking at a project that by all outward release metrics is a success and knowing that the people behind it suffered or are suffering as a result of what brought it into being.

Strange Scaffold has so many games in production, and you’ve already released a fair amount of projects. I’m curious how you judge success for the studio.

It really affects your creativity when the game you’re making is going to determine the success and failure of your entire career. Unfortunately, the games industry is organized in a way that most studios operate within a mentality of: ‘If this game does not sell above a certain threshold, we don’t survive.’

Every Strange Scaffold game is designed and developed with the intention that everyone gets to walk away, including me, if a game doesn’t sell enough copies. And I cannot tell you how much we have seen people bloom within this kind of environment, where the game that they are making and the creative goals that they are reaching are focused on execution and growth rather than results.

We want to make games better, faster, cheaper, and healthier than the industry assumes is possible and that starts with identifying different goals and processes. If everyone is making games the same way or under the same conditions, you end up with games that feel the same because they’re invisibly calculated to suit the same pipelines, production timelines, and ideals.

Two of your upcoming games are so vastly different in gameplay and aesthetics. Sunshine Shuffle is a cute, poker game and El Paso Elsewhere is your Max Payne-inspired action shooter.

I don’t want to sell people one game: I want to sell them five. I want to take players on an ongoing, evolving journey of creativity, and seeing that already happens across our titles keeps me going.

When someone comes up to me and says, ‘Hey we’re trying something different with our studio because of the results you’ve seen with Strange Scaffold’ or when someone tells us that one of our games saved them or affected them in some way, it makes the difficulty of standing by and advocating for a different model worth it. When you make more, different games, you can affect people in more ways.

To bring us back around to what we were talking about in regard to sustainability and creating an environment where people feel valued: something I’ve learned through my experience building Strange Scaffold with sustainability in mind is that the one thing you can invest in time and time again and always get a return on is people.

If the priority of your processes is the growth and safety of the people you work with, your games can only get better, too.