Attorney General Jeff Sessions, one of the first members of the Republican establishment to ally himself with then-candidate Donald Trump, appeared on Tuesday before the Senate Intelligence Committee. In his testimony, Sessions sought to staunch the increasingly rapid flow of embarrassing information from the Trump White House. The attorney general is near the center of multiple controversies dogging Trump. One is the firing of FBI Director James Comey, which Sessions recommended in a memo, for reasons that are still unclear. Another is contacts between Sessions and Russian ambassador to Washington Sergei Kislyak, whom Sessions has variously claimed he did not meet with during the campaign, then twice, and now, perhaps, three times. The third alleged meeting with Kislyak, during a campaign event at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, was one of many important particulars that Sessions claimed he could not remember. He answered more than twenty questions with some version of “I don’t recall,” “I don’t recollect,” or “I don’t remember.”

Combined with last week’s testimony from Comey, today’s hearing crystallized the tenor of Washington under the Trump administration. Much of the government seems bogged down in litigating the Russia controversy and strange happenings in the Oval Office, where the half-life of presidential confidences has never been shorter. Today, Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., insisted that, on top of their Russia investigation, his committee was continuing to oversee the intelligence community’s $50 billion-plus budget and considering the renewal of major, controversial legal authorities for government surveillance. In public, however, not much aside from the Russia is getting done.

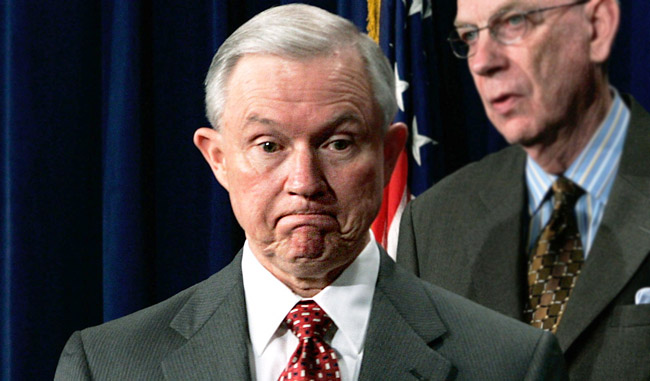

Sessions, a small man whose grey hair cuts against his boyish, almost elfin appearance, arrived nine minutes late, wearing his usual expression of slightly startled amiability. He sipped from two glasses of ice-water as he tried to convince the committee of how little he could remember despite a sincere desire to help. The campaign moved so quickly, Sessions said, that he often didn’t keep a diary or contemporaneous notes. He could not say with absolute certainty who he did and did not meet with, what was discussed, or who other members of the Trump campaign might have met with. “If I don’t qualify it, you’ll accuse me of lying,” he said, in response to an aggressive series of questions from Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif. “I don’t want to be rushed this fast. It makes me nervous.”

Sessions was unequivocal about at least one thing. He said he never sought or received intelligence relating to Russian efforts to interfere in the 2016 election. “I know nothing but what I’ve read in the paper,” he said.

Sessions’ admittedly poor and incomplete memory sharpened up considerably when the time came to discuss a fateful meeting between Comey and Trump in the Oval Office in February. In his own testimony, Comey said that Trump asked to meet with him alone and that Sessions was the last one out of the room. Then Trump, according to Comey, brought up the FBI’s investigation into Michael Flynn, his former national security adviser. Flynn had resigned the previous day, and Trump, Comey alleged, said “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go. He’s a good guy.”

Today, Sessions corroborated that the meeting between Trump and Comey had taken place, and that Comey approached him the following day with concerns. “I do recall being one of the last ones to leave,” Sessions said. “Did you decide to be one of the last to leave?” asked Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla. “I don’t know how that occurred,” Sessions replied. He did differ from Comey on two points. In Sessions’ version of events, it was Comey’s job, not Trump’s, to make sure that their conversations did not stray into active investigations. And Sessions denied remaining silent when Comey brought up his concerns about being left alone with the president. Instead, Sessions said, he told Comey that the FBI and Justice Department “needed to be careful” about following their own guidelines.

Then there were the things that Sessions could perhaps remember, but could not discuss— his conversations with Trump. He refused to say whether he had discussed pardons with Trump; or whether they had talked about the Russia investigation; or how Trump had made the decision to fire Comey, a decision that initially rested on a memo Sessions himself had signed, but which Trump later said, in an interview with NBC’s Lester Holt, came as the president mulled the Russia investigation. Sessions explained his refusal to answer these questions by citing “long-standing department policy,” but ran into some difficulty when asked by Harris exactly what that policy was. He had not read the policy; nor had he asked that the policy be provided to him. He had “talked about it,” he said, although the it that was talked about may not have been a policy after all. Instead, Sessions said, it was “the real principle” — that the Constitution guarantees what Sessions called the president’s “confidentiality of communications,” terms that appear in certain legal decisions but do not appear in the Constitution. “It would be premature for me to deny the president a full and intelligent choice about executive privilege,” Sessions said. Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., took a different view, telling the attorney general, “You’re impeding this investigation.”

Evidently, Sessions felt that he could not speak about anything that could conceivably fall under executive privilege in the future, whether or not that privilege had actually been invoked. He continued to insist that there was a written rule, somewhere, supporting his position. He promised Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., that he would track it down and provide it to the committee in the future. More than an hour after the hearing ended, the Justice Department provided reporters with a statement pointing to a 1982 memo justifying an attorney general’s refusal to answer Congress’s questions.

His Deputy Under Fire, Too

In the run-up to the hearing, Sessions cancelled a previously scheduled appearance before a Senate appropriations subcommittee, where he was supposed to discuss the Trump administration’s multi-billion dollar budget request for Justice Department. As a candidate, Trump vowed to be a “law and order” president, one who would lean heavily on his hardline attorney general to remake core elements of the country’s criminal justice and immigration systems. Sessions referenced this agenda in his opening statement on Tuesday. “The gangs, the cartels, the fraudsters, and the terrorists — we are coming after you,” he said. But instead of showing up to explain how public money would be spent in the service of that evolution, he sent Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein in his place. Rosenstein took the heat for his boss on matters not only related to the Russia investigation, but also on the critical and wide-ranging work of his department’s new law-and-order agenda.

“I won’t mince words, you’re not the witness we were supposed to hear from today. You’re not the witness who should be behind that table. That responsibility lies with the attorney general of the United States,” Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., the committee’s ranking member, said in his opening remarks. “Attorneys general of the past did not cower at the request of congress to oversight responsibility, and they didn’t agree to come and then cancel at the last minute and then send their second-in-command in their stead.”

Noting that the administration’s multibillion-dollar budget request includes hundreds of millions of dollars in cuts to assistance provided to victims of crimes, as well as support federal law enforcement investigations, Leahy questioned Sessions’ capacity to lead the Justice Department. “I want to know how he believes he can credibly lead the Justice Department, for which he’s requested $28.3 billion, amid such distressing questions about his actions and integrity,” Leahy said, adding that the department’s workforce deserves a justification from Sessions for the priorities reflected in the Trump administration’s budget. “He owes them that courtesy because the president’s budget request for the Justice Department is abysmal.”

Rosenstein was peppered with questions about the Russia investigation. In May, Rosenstein defended a memo he signed laying out his criticisms of Comey’s handling of the Hillary Clinton email investigation and, in doing so, noted that he had discussed with Sessions his negative view of Comey’s behavior last winter. He repeated the claim on Tuesday. Yet while Rosenstein declined to say who directed him to write the document, Sessions, hours later, testified that the president requested assessments on Comey’s fitness to lead the FBI from both men. This prompted Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, to suggest Sessions was selectively choosing which communications with Trump to disclose to lawmakers and which to keep secret.

Rosenstein declined to describe the scope of Sessions recusal Tuesday, citing the ongoing nature of the investigation. “In matters in which he’s recused, I’m the attorney general, and therefore I know what we’re investigating — he does not,” Rosenstein said. “He actually does not know what we’re investigating and I’m not going to be talking about it publicly.” The deputy attorney general also testified that he and the president have not discussed the appointment of former FBI director Robert Mueller as special counsel to lead the Russia investigation. He shot down reports of any involvement, on his part, of reported plans to remove Mueller from his post. “There is no secret plan that involves me,” he said.

Sessions, for his part, said he hadn’t discussed removing Mueller with anyone. “I have known Mr. Mueller over the years and he served 12 years as FBI director. I knew him before that. I have confidence in Mr. Mueller,” Sessions said. “I know nothing about the investigation. I fully recuse myself.”

Top photo: A microphone on the witness stand before a hearing where U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions testified before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on Capitol Hill in Washington on June 13, 2017.

The post Jeff Sessions Can’t Remember Anything appeared first on The Intercept.