When Molson Coors disclosed earlier this year that it considered the advent of legal marijuana to be a significant risk to its business, the company was coming down on one side of a contentious debate that has accompanied the movement to bring pot out of the shadows and into the world of taxed and regulated consumer products.

In Colorado, a pioneer in legalization, advocates centered their campaign on the argument that marijuana was far safer than alcohol, and therefore should be treated in at least a similar way.

That argument, though, becomes moot if marijuana is not actually a substitute for alcohol, but rather a complement. In other words, if getting high means you also drink more, it doesn’t matter if getting stoned is safer than getting drunk.

Because the federal government has long starved financing for research into cannabis, there is much still to learn, but early results do seem to suggest that what is intuitive is also true: that pot is a substitute — not just for alcohol, but for opioids, too.

“Although the ultimate impact is currently unknown, the emergence of legal cannabis in certain U.S. states and Canada may result in a shift of discretionary income away from our products or a change in consumer preferences away from beer,” Molson Coors Brewing Company warned in its filing.

The booze industry is not ignoring the threat, either. Several alcohol companies and alcohol industry organizations have helped fund the campaigns against marijuana legalization initiatives, which suggests that they are convinced enough of the theory to put money behind it.

An analysis I did of preliminary liquor sales data from Oregon suggests that the concerns of the industry may have merit, and that legal marijuana may indeed be causing people to consume less hard alcohol.

How recreational marijuana impacts alcohol consumption could be the most important financial and public health impact of its legalization. While marijuana use is not without problems, alcohol is responsible for roughly 88,000 deaths a year, and excessive drinking is estimated to create an economic cost of roughly $250 billion.

Voters in Oregon legalized marijuana in 2014, via Measure 91. In October 2015, the state began allowing recreational sales to adults over the age of 21, but cities and counties were given the ability to ban these businesses, so some did not allow recreational sales to take place. This makes it possible to compare hard alcohol sales in the parts of the state with recreational marijuana stores to sales in those jurisdictions without them, using data from the Oregon Liquor Control Commission, or OLCC.

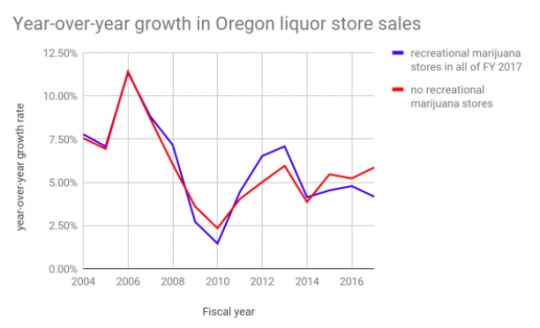

In this analysis, Oregon municipalities were divided into two groups: cities that had at least one store selling recreational marijuana throughout OLCC fiscal year 2017 (summer 2016 to summer 2017) and cities which never had recreational marijuana sales before July 2017. Store data is based on information from the Oregon Health Authority and OLCC.

From fiscal years 2016 to 2017, all liquor sales in all cities with recreational marijuana locations grew by just 4.17 percent. By comparison, in cities without marijuana stores, all liquor sales grew by 5.86 percent. While a small difference overall, this was the biggest gap in the growth rate between these two groups going back 14 years. In previous years, the growth rate for these two groups tracked fairly closely.

Alcohol sales dipped after fiscal year 2016 in areas with pot stores.

Of course, other factors could be at play, and this is only a single year of data. Cities that allow marijuana sales tend to be more liberal. In addition, a large number of Oregonians live near the border with Washington state, which privatized liquor sales in 2012 and began recreational marijuana sales in 2014. Still, the notable divergence that occurred after the first full fiscal year of recreational marijuana sales is an intriguing result — especially when combined with other research that shows people might be substituting marijuana for other drugs.

While attempts to study this question are inherently limited by the fact that marijuana only recently became legal in a few places, there is some research which indicates that state-based approval of medical marijuana was associated with a 15 percent reduction in alcohol sales. The study looked at alcohol sales in counties before and after medical marijuana was adopted and compared them to sales in neighboring counties in other states. Similarly, a new report from Cowen Research found that binge drinking was lower in states that legalized marijuana.

Other research related to this issue has been more mixed. One Rand study found that medical marijuana was associated with a small increase in deaths related to alcohol poisoning in people under 21 but a larger reduction in alcohol- and opioid-related mortality in older adults.

Other research has found that states with medical marijuana dispensaries saw a relative decrease in opioid deaths. This suggests that marijuana is also a substitute for other, more dangerous substances beyond alcohol. Just this month, two new studies were published in JAMA Internal Medicine. One found that adult-use marijuana laws were associated with a 6.38 percent lower opioid prescription rate among Medicaid patients. The other found a reduction in the number of opioid prescriptions filled among Medicare patients after medical cannabis dispensaries opened in their states.

Importantly, only one year of data exists from Oregon, and you would expect any substitution effect to at first be relatively small. Habits and addictions are inherently sticky behavior. If there is a substitution effect taking place, you wouldn’t exactly expect current heavy drinkers to immediately become cannabis users. Instead, it is more likely that some people who might have become heavy drinkers would instead use cannabis.

This analysis is only based on preliminary data, but highlights a point of interest. It will take several years to have enough data for definitive conclusions about the impact of full legalization. But comparing cities that decide to allow recreational marijuana stores in Oregon, Alaska, Nevada, and Massachusetts to cities that don’t could prove to be a very useful source of information.

While Colorado and Washington State were technically the first to legalize marijuana, they both had medical marijuana systems for years that made it very easy for people to access marijuana from dispensaries or collective gardens. It would be tough to separate the impact of very liberal medical marijuana laws from the impact of recreational marijuana. Oregon, Alaska, Nevada, and Massachusetts all had either limited official medical marijuana dispensaries, or only for a brief period, before full legalization.

Across multiple states, local governments that are deciding how to treat recreational marijuana are indirectly taking part in a massive natural experiment. The eventual result could impact marijuana, alcohol, and public health policy for years to come.

The post There’s Real Evidence That Legalizing Pot Can Reduce Drinking appeared first on The Intercept.