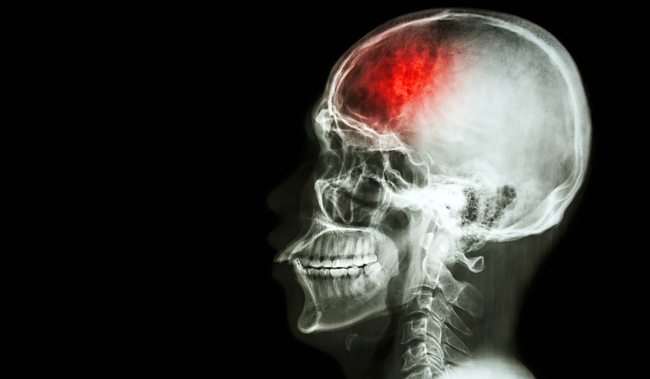

It may now be possible to diagnose CTE in living test subjects. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a progressive, degenerative brain disease often found in patients with a history of concussions and other head injuries. Up until now, the only means of testing for CTE involved intricate postmortem testing on the brains of the deceased.

Dr. Julian Bailes, one of the lead researchers in a study at UCLA, said that he will soon be publishing a 20-subject study which establishes that they’ve successfully diagnosed CTE in living subjects, including former Dallas Cowboys running back Tony Dorsett, former New York Giants defensive lineman Leonard Marshall, and former Buffalo Bills offensive lineman Joe DeLamielleure.

CTE has been found in the brains of former pro wrestlers Chris Benoit and Andrew “Test” Martin, former NHL players Rick Martin, Bob Probert, Reggie Fleming, and Derek Boogaard. It’s been found that 76 of 79 former NFL players tested showed evidence of CTE. In the tragic suicides of Dave Duerson and Junior Seau, both men shot themselves in the chest, so their brains could be tested after their deaths.

“It gets old to diagnose a disease after someone’s dead — you can’t intervene or help them,” Bailes said in an interview, adding that he and his research team first detected CTE in the brain of deceased NFL player Mike Webster in 2004. “It wasn’t much fun after a while. When you’re diagnosing after death, you can’t follow the disease with studies over a period of time. You can’t develop treatment or drugs over a period of time. So three years ago, we set aside money for research and worked on a technique at UCLA where we used a special PET scan to detect tau protein, which is associated with CTE.”

The likelihood of someone like Muhammad Ali having CTE is extremely high, but mood indicators and memory loss are not always enough. Other indicators have included other dementia-like symptoms, including violent outbursts, depression, anxiety, suicide, and at worst, the murder-suicide of pro-wrestler Chris Benoit and his family.

How do athletes avoid CTE? The simple answer is obviously don’t get punched or hit in the head for a living, but intentional or not, head injuries are a risk in almost every sport. Pro wrestling is the last place someone should actually hurt themselves, given that it’s “fake” hurting people, but not everybody is accurate with their strikes. Unfortunately, some people are just really, really bad at it. The longevity of a wrestler is entirely dependent on… well, nothing, realistically. Not everyone can be crazy ripped old man Ricky Steamboat. Most wrestlers are already irreparably damaged in one way or another by the time they hit their peak because most people don’t even take care of themselves properly (shout out to every indie wrestler who read that and went lol, no we don’t!).

Concussions and traumatic brain injuries aren’t taken anywhere near as seriously as they should be, and this could be an actual game-changer. You see this awful, regressive attitude a lot in hockey communities, that if you change a thing, it’s horrible. That’s not the good ol’ hockey game I grew up with! Sure, let guys punch each other’s brains in when they’re supposed to be shooting a tiny piece of rubber past a human pillow fort instead. Who cares if these guys end up suffering from mood swings, depression, suicidal thoughts, extreme anger, and then go ahead and harm themselves or others or both? That same deathgrip seems to apply to wrestling and football, and any other sport where the safety of a participant comes second to tradition and toxic masculinity. Just suck it up, right? Play the game. Get in the ring. Get back on the field.

If CTE can be detected in living test subjects, all of that could change. We’re not gonna tear down hundreds of years of damaging patriarchal views (yet, we’re working on it), but if harmful trends can be identified, we can learn more about how to stop them. It helps legitimize an issue people are willing to brush off for the imagined sanctity of a game. If more athletes are found to be in danger than originally thought, it forces leagues and companies to seriously reconsider their still-lax safety standards regarding head injuries, and penalizing those who willfully ignore the consequences of hits to the head. Not only that, but it could have far reaching implications for treating war veterans, as well, and help advance studies on the effects and possible treatments for Alzheimer’s.

Of course, some players might not want to know if they have it. Here’s former NHL player Matthew Barnaby, via the TSN article linked above:

“It’s a big business and there’s a lot of money involved. We all know as players, we know what management thinks of guys who have had one, two, three concussions, whatever the number may be. Every time you have one more diagnosed, you’re thought of as damaged goods and your price tag when you become a free agent is going to go down. There might not be anyone come calling.”

That’s not the case, however, with Toronto Maple Leafs goaltender James Reimer:

“This is like that question, ‘Do you want to know right now the day you are going to die?’ It’s not an easy question to answer. But I think the more knowledge you have about your medical situation, the better. It helps you make more informed decisions. If you have a torn ankle, you want to know how badly torn it is. Same with your brain, if it’s damaged, you want to know how bad.”