The title character of the CW’s latest DC Comics drama, Black Lightning, has a messy real-life origin story. In the late ‘70s, DC was very belatedly ready to introduce its first comic with an African American hero — sort of. The plan wasn’t for Black Lightning, but for the Black Bomber, a racist white man who, under stress, would transform into a black man with powers.

“[It] was a doubtless well-intentioned but truly offensive idea,” according to comics veteran Tony Isabella. “Each script featured the white guy rescuing a black person and then grouse that he risked his life for — and this is a quote from the script — a ‘jungle bunny.’”

Isabella was able to pull DC back from this most precarious of branches they’d climbed onto with the Black Bomber idea, and instead pitched them on Black Lightning, aka Jefferson Pierce, an erudite Olympic decathlete turned inner city high school teacher who educates by day, and — with the help of various electricity-based powers — fights crime by night. Despite the novel setting for DC, interesting powers, and a cool costume (which included mask with an afro wig attached that, along with healthy use of a jive dialect, helped conceal Pierce’s true identity), the title was canceled after only 11 issues, in part because DC was cancelling a lot of titles at the time, in part because of a royalties dispute with Isabella that led to a shameless imitation called Black Vulcan appearing in the Super Friends cartoon instead of Black Lightning.

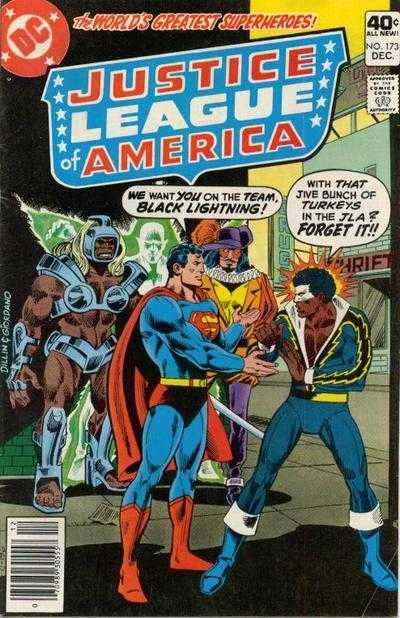

Black Lightning’s gone in and out of vogue in the decades since (including a healthy run as a member of the Batman-led Outsiders super team), and for a time was mostly infamous for the above cover. (In fairness to him, the guys behind Superman do look like jive turkeys, don’t they?) His translation to TV has had its own bumps, albeit nothing nearly as ridiculous as the Black Bomber pitch. Originally developed at Fox, in another attempt to expand DC’s TV presence beyond the CW, it has instead landed at the home of all the other Greg Berlanti-produced shows, where it will debut tonight after The Flash.

The finished product stars Cress Williams(*) as Black Lightning, and shares some trappings with the other Berlanti shows: a large family presence (including Christine Adams as ex-wife Lynn, and Nafessa Williams and China Anne McClain as daughters Anissa and Jennifer), a cop (Damon Gupton’s Inspector Henderson) who’s not sure what to make of this superpowered vigilante, a trusty tech support sidekick (James Remar as Peter Gambi, who in the comics is a tailor specializing in making costumes for supervillains), and an archnemesis (Marvin Jones III — aka rapper Krondon — as vicious gangster Tobias Whale).

(*) As a tall, muscular black man, Williams has inevitably been cast as athletes, or in athletic-adjacent roles, for much of his career: basketball (he was D’Shawn Hardell on the original Beverly Hills 90210), football (jock-turned-mayor Lavon Hayes on Hart of Dixie), baseball (his first screen credit was an episode of the sitcom Hardball), sportscaster (Sports Night) and sports dad (he was Vince’s father in the later seasons of Friday Night Lights). Finally, that physique lands him a lead role, and in one of the series’ few comic moments early on, he opts to take the stairs rather than the elevator when confronting a bad guy in a high-rise, explaining, “Just getting back into this. A brother needs all the exercise he can get.”

But showrunners Mara Brock Akil and Salim Akil (Being Mary Jane, The Game) are new to the Berlanti-verse(*), and they bring a specific point of view to what’s been a successful but pretty rote formula for these series. This is, like Netflix’s Luke Cage, a superhero show keenly aware of its hero’s skin color and how that makes the world respond to him, in both his civilian and costumed guises. Jefferson Pierce is an all-American success story, but he still gets racially profiled — while driving to a school fundraiser in a tuxedo, his daughters in the backseat — by two trigger-happy cops who assume he’s the liquor store robber they’re looking for. Later, as Pierce — who has been retired from superheroics for nine years when the show begins — exits a crime scene, another white cop orders him to “get your black ass on the ground.” The show casually quotes Dr. King, has Jennifer derisively refer to her more woke older sister as “Harriet Tubman,” and is as interested in the social problems of the neighborhood as it is in seeing Black Lightning and Tobias Whale go to war again.

(*) This show is, for the moment, not set in the same reality as the ones featuring Flash, Green Arrow, and the Legends of Tomorrow, the better to let it stand on its own. Just don’t be shocked if, depending on the ratings, Oliver Queen falls through a dimensional portal at some point to hang out with Jefferson Pierce.

The series doesn’t always tackle these ideas gracefully — or, at least, subtly: its fictional city is called Freeland. But the canvas the Akils are painting on feels much richer for looking beyond basic good vs evil, time travel, doppelgangers, and all the other tropes of the genre. The show feels different from the other series — and sounds different, too, thanks to a soundtrack filled with original rap songs by GodHolly. And beyond the myriad issues of race and class and politics, making Black Lightning an older hero reluctantly coming out of retirement creates a new dynamic, and the charismatic Williams ably conveys just how sick and tired Pierce is of all the reasons he has to once again put on the light-up suit and start hurling electricity around.

There are certain aspects of the formula that just can’t be worked around, and given that all the prior Berlanti shows (other than maybe Legends of Tomorrow) are perpetually at risk of drowning in angst, the fact that this series starts from a grimmer and more sober place leaves less margin for error. But it’s a promising start, and a long-overdue showcase for Williams.

Back in the day when superhero fans first met Jefferson Pierce, comics writers would sometimes put “Black” at the front of a superhero’s name (or a supervillain’s) just to highlight the novelty of a man of color in what had long been a Caucasian-dominated field. It often felt diminutive, as if Black Lightning or Black Panther or Black Goliath were somehow less than counterparts who didn’t have to be referred to as White Batman or White Iron Man. Here, though, the name feels inspirational: he is a hero for this neighborhood in this city, at this difficult time to be black in America.

Alan Sepinwall may be reached at sepinwall@uproxx.com. He discusses television weekly on the TV Avalanche podcast. His new book, Breaking Bad 101, is on sale now.