SHOWS

Covers Books

EVENTS

FEATURED

BRANDS

TRAVEL,

DRINKS & EATS

DRINKS & EATS

Latest

Johnny Blue Skies Just ‘Leaked’ Their Physical-Only Album Online Ahead Of Its Release

Johnny Blue Skies & The Dark Clouds announced the album Mutiny After Midnight last month, setting it for a March 13 release. Interestingly, Johnny (a new moniker of Sturgill Simpson) decided to release the project only on physical formats: vinyl, CD, and cassette tape. But, ahead of that release, they've actually shared it online first, as a sort of "accident." Currently, the whole album is available on YouTube as a single 45-minute upload. They shared the news in an Instagram Story, writing, "Ooops,.mighta just posted the whole f*k'n album on YouTube....for the real ones." Johnny previously shared a statement about…

Sombr Believes The UK Beats The US ‘In Terms Of Iconic Acts’

The US and UK music scenes aren't exactly the same, but there is a lot of overlap. Sombr, for example, had his 2025 debut album I Barely Know Her peak at No. 10 on the charts from both territories. Consequently, he was on hand for the BRIT Awards this past weekend, where he pledged his allegiance to UK artists. In a red-carpet interview with NME, the interviewer noted how Sombr has said previously that something about the UK resonates with him and she asked what it was. He responded: "It’s the music that comes from the UK. In my opinion:…

Anderson .Paak Explains Why It Was So ‘Important’ For Him To Star In ‘K-Pops!’ Alongside His Son

Anderson .Paak is a singer, drummer, and now, director as his debut movie, K-Pops!, is in theaters. It debuted this past weekend, and at the premiere, he discussed hos meaningful it was to star in the moving alongside his son, Soul Rasheed. .Paak told Variety: "I could have pulled from a lot of things in my life, but it was important to do a family comedy where I'm sharing the screen with my son -- for people to see Black families, for people to see joy and happiness." .Paak also told Rolling Stone about the personal significance of the film's…

Alex Warren Has A Bonkers ‘Fever Dream’ Featuring Paris Hilton In His Chaotic New Video

Last week, Alex Warren dropped "Fever Dream," which was teased as being an "introduction into Warren’s next chapter." The song is about Warren meeting his wife for the first time, but he takes a more literal approach to the title in the song's music video. The visual, directed by Andrew Theodore Balasia, sees Warren driving and guiding a celebrity tour when a mystery woman catches his eye. A chaotic sequence of events unfolds from there, and as for the woman, much to Warren's surprise, it ends up being Paris Hilton. At that discovery, he wakes up. Warren recently talked about…

The Best Physical Media Releases Of February 2026

Streaming services are the primary way a lot of people consume their media of choice, whether that be music or TV shows or movies. Not everybody is on board, though, and some who are are getting tired of it. Regular price increases and limited streaming libraries have some consumers returning to physical media, preferring vinyl and CDs and DVDs and more, objects they can hold and own without fear of losing access, over streaming options. Companies are more than happy to support this wave: Whatever you might be into, each month brings a slew of new releases that has something…

SNX: The Union x Fragment x Air Jordan 1 And This Week’s Best Sneakers

Welcome to SNX, your weekly roundup of the best sneakers to hit the internet. Let's all take a second to gently laugh at this Nike x Stranger Things collab: the Vecna Air Foamposite One. Look, we don't like to be negative but what's going on with this shoe? Vecna is such a textured dude, imagine the different fabrics and materials Nike could've pulled together to make something that feels as iconic as the character (say what you will about the final season of Stranger Things, but Vecna's design is going to live on beyond this decade). But instead of doing…

Yeat And EsDeeKid Take Over Drake’s Mansion In Their New ‘Made It On Our Own’ Video

Yeat has been one of the most exciting new rap stars of the decade so far, and he's set to continue his ascent soon with the release of a new album, ADL (short for A Dangerous Lyfe). The project doesn't have an announced release date quite yet, but we do have some new music: Today (February), he teams with Liverpool rapper EsDeeKid for "Made It On Our Own." The video, directed by Director X, is a big one, as it sees the two rappers taking over Drake's Toronto home. Caleb Williams and Cole Bennett make cameos in the visual, and…

Nettspend’s Debut Album Is Coming Soon As He Gives ‘Early Life Crisis’ A New Release Date

Nettspend has been on a rapid ascent over the last few years. It started with the teenage rapper's "Drankdrankdrank" going viral on Twitter, and that was followed by his debut mixtape, Bad Ass F*cking Kid, in 2024. Fans are still waiting for a proper album, but they won't have to wait much longer, as Nettspend just announced the release date for Early Life Crisis. The project is set to land soon, on March 6. A description on Nettspend's web store notes of the album: "Nettspend's early life crisis album reflects a generation being ushered into adulthood too quickly. It channels…

Alex Warren Starts A New Chapter With The Punchy Single ‘Fever Dream’

Alex Warren is coming off a huge 2025 that saw "Ordinary" become one of the most-streamed songs in the world. His 2026 is off to a strong start, too, with a memorable performance at the Grammys earlier this month. Now, he's gearing up to launch a new era with the release of today's (February 27) new single, "Fever Dream." On the jaunty tune, Warren sings about meeting his wife for the first time: "Left the room the second that you walked in, somethin' like a fever dream / Haven't slept in weeks, I think I'm seeing things / Like our…

Anderson .Paak Links With aespa To Blend Their Styles Together On ‘Keychain’

Way back in 2022, it was announced that Anderson .Paak was making his directorial debut with a movie called K-Pops!. Now, the movie is playing in AMC Theaters nationwide, and today (February 27), .Paak has shared "Keychain," a collaboration with aespa from the movie. The track blends .Paak's hip-hop and funk sound with aespa's K-pop sensibilities. In a statement, .Paak says: "I'm excited to join forces with aespa on 'Keychain.' K-POPS! is all about connection, and this track reflects that perfectly. We come from different worlds, but we're connected by the same passion for music." aespa adds, "Working on 'Keychain'…

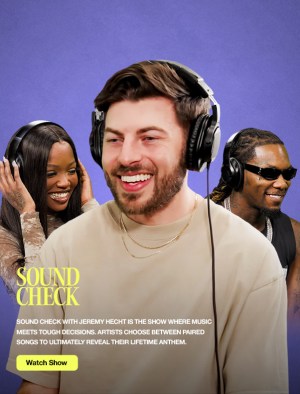

Yung Miami Is Looking For A ‘God-Fearing’ Man Worth At Least $100 Million, She Reveals On ‘Sound Check’

Uproxx's Sound Check is the show where music meets tough decisions, and along the way, we get to learn a little more about the artist. On the latest episode, the guest is Yung Miami, and during the this-or-that song-choosing game, she laid out some of the attributes she's looking for in a potential partner. Pitting Beyoncé's "Dangerously In Love" and Keyshia Cole's "Wonderland" against each other, host Jeremy Hecht asked which of the songs "feels like 'Yung Miami in love' more." After listening to snippets of both, she went with "Wonderland," explaining how her mother is a big fan of…

HARD Summer 2026 Boasts A Lineup Led By Kali Uchis, Shygirl, 2hollis, And Others

There's no shortage of standout summer entertainment options in the Los Angeles area, and that's especially true thanks to the HARD Summer Music Festival. Now, fans can start planning for this year's installment, as today (February 25), organizers have announced the lineup. The fest's lineup, as it generally is, is electronic-leaning, but there's some great stylistic variety. Highlights include Kali Uchis, 2hollis, Shygirl, DJ Snake (DJ set), Zedd, Tokischa, Zach Fox, and more. Everything goes down at Inglewood's Hollywood Park (right by SoFi Stadium) on August 1 and 2. Tickets go on sale starting February 27 at 10 a.m. PT,…

Laufey Is Expanding Her Beloved Album ‘A Matter Of Time’ With A New Deluxe Edition

It's been a big February for Laufey: At the top of the month, her 2025 album A Matter Of Time picked up a Grammy win in the Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album category (her second time being nominated in, and winning, the category). Now, she's wrapping up the month with some news: Today (February 25), she announced A Matter Of Time: The Final Hour, a deluxe edition of the album arriving April 10. It adds four songs to the tracklist and one of them, "How I Get," is out now. In a statement, Laufey says of the song: "'How I…

Lauryn Hill, Shakira, And Wu-Tang Clan Are Among The First-Time Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Nominees In 2026

In a superlative-obsessed world, there are few, if any, bigger honors in music than getting inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame. Even being nominated is a big deal, and now a new crop of artists can add that to their resumes: Today (February 25), the Rock Hall announced the list of nominees for its 2026 induction class. This year, there are 17 nominees: The Black Crowes Jeff Buckley Mariah Carey Phil Collins Melissa Etheridge Lauryn Hill Billy Idol INXS Iron Maiden Joy Division/New Order New Edition Oasis Pink Sade Shakira Luther Vandross Wu-Tang Clan Among those, appearing…

The Best Mitski Songs, Ranked

I did not originate this theory -- I saw it on Reddit, I think, though I can't say that for sure as I haven't been able to recover the post -- but I'll share it here anyway: Mitski's career can be cleanly divided into two-album eras. There's "Embryonic Mitski" (2012's Lush and 2013's Retired From Sad, New Career In Business), "Indie Rock Mitski" (2014's Bury Me At Makeout Creek and 2016's Puberty 2), "Disco-Rock Mitski" (2018's Be The Cowboy and 2022's Laurel Hell), and "Country Noir Mitski" (the two most recent records, including the upcoming Nothing's About To Happen To…

Hotels We Love: Andaz Maui Is Peak ‘Slow Hawaii Vacation’

There are a lot of "right" ways to do Hawaii, and... I genuinely love most of them. I love the version where you go a little rugged — where the roads get thinner, there are creepers dangling all around you, and cliffs to jump off around every bend in the road. I love the surf version, too -- where the waves dictate the pace, meals are there as fuel, and the fear of offending a local in the water has me at my most courteous. But over the past few years, I've found another version of Hawaii that is tough…

The Stacked 2026 Shaky Knees Lineup Features Gorillaz, Twenty One Pilots, And Much More

Atlanta's Shaky Knees festival is routinely awesome, and they're really bringing it in 2026. This year's edition is going down from September 18 to 20 at Piedmont Park, and today (February 24), organizers shared the lineup. The Strokes lead on Friday, which will also feature Turnstile, Fontaines DC, Geese, Danny Elfman, Hot Mulligan, Snow Strippers, Ben Howard, Alice Phoebe Lou, Goldford, and Cartel. Saturday is led by Twenty One Pilots, as well as Piece The Veil, The Prodigy, Pavement, Jimmy Eat World, Blood Orange, Peach Pit, Taking Back Sunday, Minus The Bear, Wolf Alice, The Rapture, Congress The Band, Psychedelic…

PinkPantheress Is Now The First Woman And Youngest Artist To Win Producer Of The Year At The Brit Awards

PinkPantheress has made it clear that she thinks of herself more as a producer than as a performer. Now the folks at the Brit Awards are giving PinkPantheress her flowers for her production, as it was just announced that for the 2026 ceremony, she will be given the coveted Producer Of The Year Award. She'll officially receive the award at the ceremony this weekend, February 28. This makes her both the first woman and the youngest person, at 24 years old, to win the award. She said in a statement, "As the first woman to win this award, I'm grateful…

Bon Iver Is Launching The New ‘Volumes’ Archival Series With The First Edition, A Live Compilation

Bon Iver has gone through a lot of eras at this point, and now they're starting to commemorate that: Today (February), they announced Volumes. A press release describes the series as "a new and recurring archival series spanning live shows, demos, unreleased recordings and other previously unheard material, presenting the many eras and multitudes that make up 'Bon Iver.'" It also says the endeavor is "modeled after Bob Dylan's Bootleg Series and the Neil Young Archives." The full title of the first release is focused on live recordings and its full title is Volumes: One "Selections From Music Concerts 2019-2023…

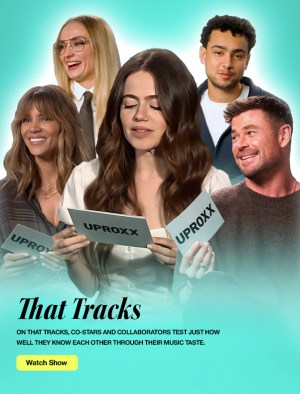

Halle Berry Makes Her Favorite Kendrick Lamar Track Very Apparent On ‘That Tracks’

Kendrick Lamar has one of the most beloved libraries in all of hip-hop, so it's hard to pick just one favorite song. In a new installment of Uproxx's That Tracks, though, Halle Berry seems to have. She and Crime 101 co-stars Chris Hemsworth and Mark Ruffalo sat down for the latest episode. In a clip, Hemsworth read the prompt, "If I'm stuck in traffic in the 101, I'm listening to my favorite LA-based artist, Kendrick Lamar. Does that track?" He added, "On certain days, for sure." Berry then chimed in, "Absolutely, hell yes," and Ruffalo added, "Would do that, too."…

A Pivotal Taco Bell Moment In Myke Towers’ Past Is At The Heart Of His New Partnership With The Restaurant

Myke Towers has become one of Latin music's biggest voices in recent years, and now he's extending his empire to restaurants. It was announced last month that he had entered into a partnership with Taco Bell. The latest product of the team-up is a new ad for the Chicken Bacon Ranch Street Chalupas, which features Towers' song "Sunblock." The collaboration actually has some personal meaning for Myke. As a press release explains, there was a day in 2015 when he was recording in Miami. All he had was $10 and no ride, so he and two friends walked to a…