Before the Affordable Care Act had even been signed into law, congressional Republicans were promising to veto it. Those solemn vows continued throughout the 2010 midterms, helping Republicans take back the House in the tea party wave.

They used that position of power to pass repeal after repeal after repeal — and to point at the Democratic-controlled Senate as an obstacle to be overcome.

In 2014 they finally took the upper chamber back. With unified control of Congress, in 2015 they sent President Obama a full repeal of Obamacare. He vetoed it. The message to activists was clear: Republicans needed to control the White House, too.

In 2016, they took the White House. And then things got real.

With the prospect of repeal actually becoming law, the House blinked in March, and Speaker Paul Ryan pulled his repeal-and-replace bill from the House floor. As flawed as the Affordable Care Act was and is, repeal would throw millions off of health insurance and drive up premiums. Republicans had nothing better to replace it with, largely because the ACA was originally a Heritage-devised concept to begin with. “Obamacare is the law of the land,” Ryan acknowledged.

Not so fast, said President Trump, never one to worry about real-world consequences. Entirely divorced from the policy discussion, Trump looked only at the politics of failure and recoiled. He piled on the House Freedom Caucus, blaming them for a loss that had many fathers. And so the Freedom Caucus said fine, we’ll vote for something and send it to the Senate, where it’ll die.

The premise behind the renewed effort in the House to pass a bill was always that: the Senate will fix whatever we do, so don’t worry about the details of what’s in ours. For the House, it felt a bit like Obama was back in the White House, with his veto pen the blankie that Republicans needed to take legislative nap. As long as voting was a dream, it was doable.

In May, Republicans were bussed to the White House for a surreal display, a celebration in the Rose Garden after repealing Obamacare in a single chamber.

As the debate moved to the Senate, Trump began to get some whiff of what was in the bill, and railed at it, accurately, as “mean.”

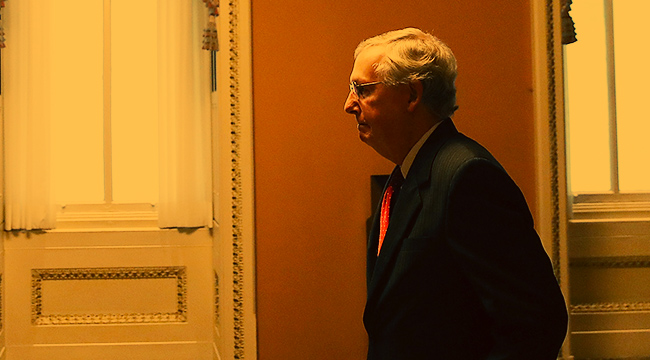

But still he demanded a vote. The promises to lawmakers that they were not really making law grew more explicit. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., promised moderates that Medicaid cuts they opposed would never actually be implemented. Somehow, that wasn’t enough, and Republicans in the center and the right revolted, the final nails being driven in simultaneously by Sens. Mike Lee of Utah and Jerry Moran of Kansas — with Moran demanding the process start over and make sure to address pre-existing conditions.

It had become blindingly clear by that point that Republicans were not willing to vote for a repeal bill that could become law. Nevertheless, Trump persisted.

The demands for a fantasy vote grew even more extreme. McConnell pushed his colleagues to vote for something — anything — just to get the bill to a conference committee, so that the two chambers could work something up and bring it back for a vote.

So he held a vote to bring the bill to the floor, with assurances that both of the party’s major projects — repeal and repeal-and-replace — would fail on the floor.

With a tie-breaking vote from Vice President Mike Pence, he succeeded, winning a day of headlines about GOP momentum, even as the votes on repeal themselves went down badly.

After dispatching with repeal and repeal-and-replace in not-close-votes, the Senate moved on to “skinny repeal” — a repeal of just a wee bit of Obamacare, just enough to get 50 votes and move to conference committee, where, somehow, the fundamental dynamics that had blocked repeal would somehow be overcome.

But wait, asked Senate Republicans, what if we pass something — and it actually becomes law? It was too much to contemplate.

Sens. Lindsey Graham, Ron Johnson, John McCain and Bill Cassidy held a press conference Thursday night in the Capitol demanding full assurance from the House that the lower chamber would not, under any circumstances, take up the bill they planned to pass and send it to the White House. If the Senate could be assured it would go to conference committee instead, they promised, then they would support it.

To be clear: they demanded a public promise that the bill they were voting for would never become law in order to agree to vote for it.

The promise Ryan offered was less than a promise. “If moving forward requires a conference committee, that is something the House is willing to do,” he offered in a late-night statement.

But he had a condition: the Senate needed to put up. Eventually. “We expect the Senate to act first on whatever the conference committee produces,” Ryan insisted.

In other words, fine, vote for your sham bill. But when the conference committee creates one more sham, y’all have to vote on it first, proving to the American people — and, more importantly, to Trump — that it is the Senate that doesn’t have the votes. Never mind that the House didn’t have the votes, either, when they thought it was real.

McCain, who returned to the Senate after a brain-cancer diagnosis to cast the dramatic vote McConnell needed to get the bill on the floor, put it as well as anybody could. Walking on to the Senate floor for the critical vote, he told reporters, “Watch the show.”

McCain joined with Susan Collins an Lisa Murkowski to give the chamber just enough votes to kill it, 51-49.

It was all a show.

The post Republicans Got Good At Symbolic Repeals Of Obamacare, But Flinched When Faced With Reality appeared first on The Intercept.