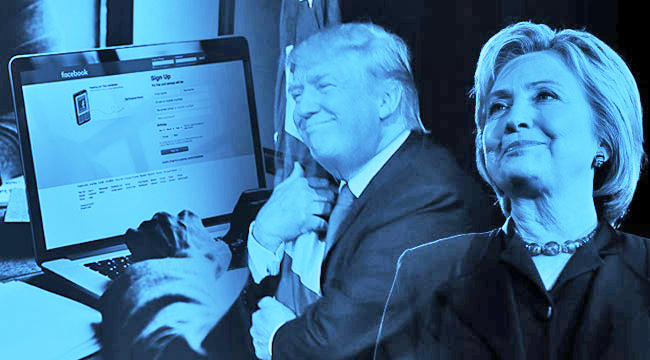

Facebook has been at the center of Election 2016, especially with the ongoing questions of propaganda and the echo chambers the social network can create. The latest wrinkle involves a claim that the Trump campaign ran a highly effective $100 million voter suppression operation that lands in a legal grey area. This also dredges up a Trump adviser’s previous admission that the campaign was involved in at least three voter-suppression campaigns. But was this operation really that effective? Or was it all just hype?

The claim, as reported by The Wrap, is that by using non-political Facebook quizzes, the Trump campaign was able to locate likely Hillary voters and then target ads at them to convince them to stay home on Election Day. The basic idea is that by using non-political tastes such as interest in different aspects of pop culture or taste in brands, algorithms are able to match those tastes with likely political preferences. Football fans might be seen as more conservative, while This American Life fans may be seen as more liberal. Once those tastes were diagnosed, anti-Hillary ads were targeted as what the campaign saw as likely Hillary voters.

It’s worth noting that using non-political content to political ends on Facebook is common practice by every political party: In 2012, the Obama campaign’s Facebook initiatives were widely touted as part of the reason he won a decisive victory over Mitt Romney. Obama used Facebook to find voters and attempt to get them out to the polls, however. The Trump campaign, on the other hand, appeared to have used the network to discourage his detractors from voting. And the plan was reportedly the brainchild of Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and shadowy data company Cambridge Analytica, which also worked on the Brexit campaign.

Cambridge Analytica has a vested interest in the belief that it can manipulate voters. The data company, founded in England, likes to sell itself as a political overmind, a service that can boil every voter down to a set of personality traits and then use that to promote a candidate over the top. The company has a checkered past in politics, as an Ad Age look at the company illustrates:

“Everyone universally agrees that their sales operation is better than their fulfillment product,” said another consultant who has worked with the company. “The product comes late or it’s not quite what you envisioned.” “What’s the old saying?” asked another source, conjuring up a metaphor to describe Cambridge Analytica. “All hat, no cattle?”

In terms of the raw numbers in Election 2016, it’s hard to argue Analytica that was successful in suppressing the vote. Hillary Clinton’s popular vote lead is currently at 2.5 million, and the Trump campaign’s win ultimately wound up being an Electoral College victory by winning razor thin margins in just a handful of states. A win is a win, but this was hardly the decisive victory some are attempting to make it out to be.

Part of this may have to do with how it’s being increasingly revealed that the seeming might of algorithms is based more on hype than fact. Facebook received some heat after it was revealed that its Trending Topics “algorithm” was actually a team of people checking the news, and its attempts to back up its hype about brilliant machines led to the propaganda fiasco currently engulfing the site. Facebook’s algorithms are essentially unable to tell the difference between an insect and a TV show, and it turns out that our own biases can easily be worked into algorithms, to the point that we can make computers behave in possibly racist ways.

It’s arguably true that algorithms can spot trends in large groups of people who happen to share the same general characteristics. Human beings are not nearly as unique, in groups, as we like to believe about ourselves. But, of course, that’s just demographic research. The claim here is that campaigns are able to use Facebook to either keep voters at home or lure them to the polls. And, if you look at the actual data, all those claims seem to be little more than promises without the results to back them up.