Netflix’s limited series High Score is an attempt to highlight video game history, a topic so large showrunner Melissa Wood admitted it could swallow up the entirety of her filmmaking career. And she’d be just fine with that, if Netflix is interested.

The show is both sprawling and narrowly focused, touching on the intensity of the early console wars between Nintendo and Sega, the differences between the Japanese and American game markets, and how gaming pioneers unleashed new ideas that radically shifted its trajectory into the multi-billion dollar market that it is today.

But it also is a limited series on small stories hidden in plain sight that changed the industry forever. In its six episodes, Wood and France Costrel highlighted the work of relative unknowns like Jerry Lawson, a Black man who first pitched the idea of a console that had interchangeable game cartridges. High Score is a series that manages to make Mario and Zelda visionary Shigeru Miyamoto a side character, not a major player, making clear the simple fact that some of the best stories about video games are often the least well known.

Uproxx spoke to Wood about High Score, the joy of working with other creatives on projects and why the show highlighted some stories and decisions over others during its six episodes. And what might be coming next if there’s more High Score in store.

Uproxx: I was just reading your Reddit AMA after finishing the series myself. What was it like to get some feedback from people who have watched?

Melissa Wood: That was fun. I’d never done that before. It’s great to talk to people directly, you don’t usually have a chance to do that. Things go out in the world so it’s nice when you have that direct line to people who’ve seen the show.

Gordon Bellamy

One thing I was thinking while watching this and I wanted to ask you about was how you choose the narrative of the show. The industry has so many stories and so many ways to explain its history, but where do you start deciding what’s important and needs to be explored?

It was really hard, actually. Because you’re right, the industry is huge. So much has happened in the last 40-something years and there’s endless stories to sort of look into. There are a few things that sort of guided our decision-making in the beginning. One was we sort of wanted to look at the industry from a personal perspective and from a different perspective. For instance, we knew that we wanted to include a music composer because we thought that this was a part of gaming that’s not really thought about really often but it’s so crucial to the experience as a player.

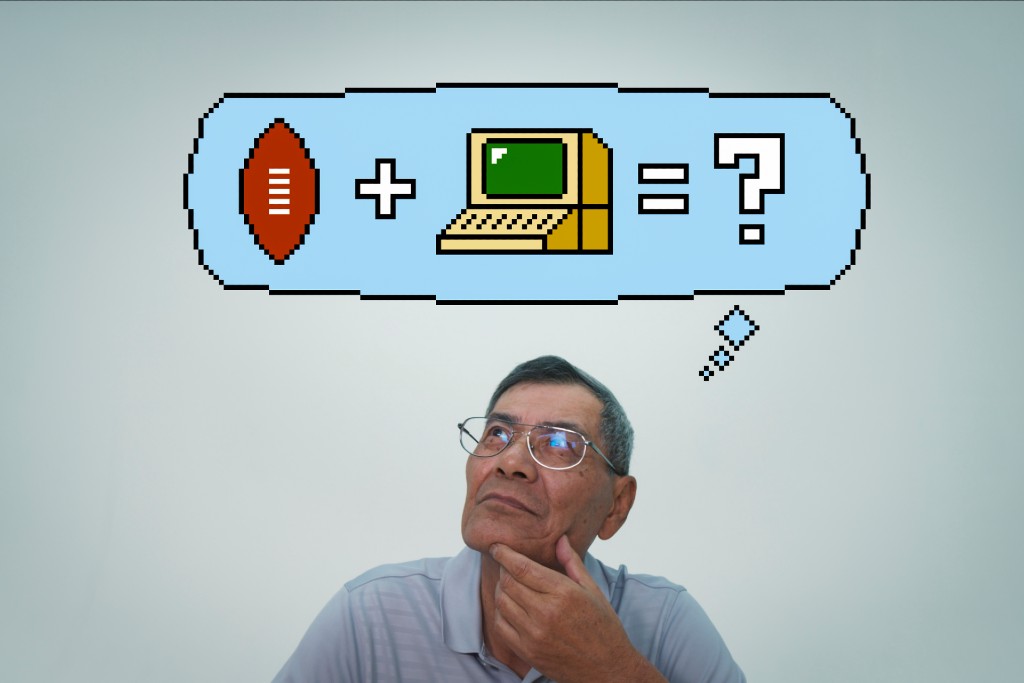

We knew that we wanted to have sort of a diverse cast of characters whose own experiences and creation would vary from each other. For instance Gordon Bellamy’s attachment to Madden, we felt like that was really special and unique and different from the other people in our series.

What we really wanted to sort of not go down the route of with our series was sort of telling the same perspective of the visionary lone creator who has a great success over and over again. We thought that would be really repetitive and thought it would sort of sell the industry a bit short in how innovative it was and how many various people had been involved in creating these games.

Once upon a time, every video game console came with a single dedicated game.

Then in 1976, a Black engineer named Jerry Lawson invented "interchangeable cartridges" and changed the industry forever

(📺: High Score) pic.twitter.com/n2KYIA1C9h

— Netflix (@netflix) August 19, 2020

I was actually going to ask about the show’s diversity. The industry as a whole, and still is today, dominated by men. Specifically straight, white men. The series does a good job to show not only how many other stories there are but also how important games are to other people, more marginalized people. I’d never really seen that in a gaming property to this scale before.

It’s so interesting because we certainly wanted the show to be diverse, we feel like representation matters. France (Costrel), my creative partner, she grew up in France so she had a completely different background than I do but we felt that games are sort of a common language. No matter where you’re from, games can be a common connection and everyone can sort of experience these worlds. So it was definitely a goal to show the diversity and a diversity of players and creators.

I’ve talked to a few journalists and read some things and a lot of people do comment on the diversity of the show. And while I’m glad people noticed that, in some ways I feel that, when we wrapped the show I was like ‘I feel like we didn’t quite meet the mark of diversity that we aimed for.’ So it really kind of shows how low the bar is and more work needs to be done in this industry.

Television is kind of the same way where things are starting to change and they’re being more active about bringing in a diverse crew and covering diverse subjects. I don’t know, I’m just sort of thinking this week with all these things going on in the news, how it’s been so noted on the series about how it’s so diverse when it could have been more so.

There’s a pretty distinct mix of visual effects in High Score. There’s archival footage, there’s some recreations of events and also some animation. Was that the product of necessity or were you able to decide what you wanted to do with each moment with a bit more purpose?

For sure we knew from the very beginning the we wanted to combine a lot of different elements to make the series as visually interesting as possible. We didn’t want it to feel historical. We didn’t want to have talking heads, then archival, then talking heads. We thought that would feel very sort of static and boring and we wanted it to feel more immersive and active.

So it was the plan from the beginning that we were sort of going to combine a lot of different materials to tell the stories. And really, in the end, it came down to the stories themselves kind of determining who could be animated or what could be archive, what could be digital. Obviously, you know stories like Jerry Lawson, who is no longer alive, we wanted to bring his story to life through animation so we could sort of connect with him as a person even though he’s no longer here. But other stories like Howard Scott Warshaw, who created E.T., he had these amazing, very visual stories he told about meeting (Stephen) Speilberg. Even though we were able to film a lot of other stuff with Howard Scott Warshaw — he was such a cool story participant, up for anything — we just thought it would be really fun to sort of bring those to life with animation and kind of have it play like a video game. So it was sort of a mix of necessity and creative vision.

It must have been really exciting when some of this was filmed. It seemed like some people were extremely game for whatever, and were really passionate about their stories. That must have really guided those decisions.

Oh yeah. It was so great because, these are creators themselves. Sometimes when you’re making a documentary you do a lot of explaining why you need to actually film material in order to show something. But everyone we worked with on this series, they knew. They were makers themselves, so they knew that they were going to have to participate to tell their stories. And we really tried to bring them in, as soon as we started talking to them on the phone and bringing them into the brainstorming because we really wanted to make whatever they did authentic to who they were.

And so obviously some people, Shaun Blum, for one, the Nintendo gameplay counselor, he was really ready to ham it up for the camera. And it works, because that’s who he is. And other participants wanted to just show their passion or be sort of poetic about what we filmed, so it really felt like a collaboration with them and it was also fun because it gave us the opportunity to sort of not repeat ourselves. We wanted every person to feel like their own story was unique and had its own stake in our series.

The series itself is firmly set in the past, at the impetus of gaming and where it starts and how it grows. It seems like it unfolds maybe not exactly sequentially, but things evolve with an exception for a brief moment in the last episode. If there are more episodes in High Score, does it continue where it left off or eventually get to the present? Or are there more stories to tell in the 70s and 80s?

Well, who knows. For now it’s a limited series. I would love nothing more than to work on iterations of High Score for the rest of my career. It’s so much fun and there are so many story opportunities still out there. So I can’t say if we were to do a second season what it would look like. But any of those things are possible. I think there are so many stories that we didn’t cover in this time frame that we would love to cover. But I think that so much has happened since then that would also be completely new territory and we certainly would have more people who were still around in the industry that would participate. So, I mean, who knows?

I do think that there’s something really appealing to the nostalgia factor and something about it being a new frontier, where there weren’t really rules yet like there is now. Where people could go and kind of test their ideas and they had more sort of freedom. So that is appealing just in the sort of stakes and creativity are all there. But I also think that the games have changed and the technology is its own sort of story these days.

I thought it was interesting that when there are new ideas and the rules of an industry aren’t there, there are inevitably lawsuits and copyright infringement and all these sort of legal situations. The show seems to not editorialize when it came to that, or maybe pick a good guy or bad guy in any of those fights. Was it difficult to tell those stories and not frame it in that way?

I mean, we didn’t really feel that was the role of this series. There’s certainly room for a series like that, there’s a way to tell that kind of story. But we just wanted to focus on the people and their contributions and let the audience decide for themselves whether… like, the violence episode, episode 5. We don’t need a really strong statement there. We just let the character speak for themselves but I think you can subtly guess where we stand there in the sort of light treatment of it.

We didn’t really feel like it was our vision or our goal to sort of tell the audience what to think of the industry. It was more about sort of sharing the experience of the people that created these games. At the same time, it was noticeable that you focused on ideas and not necessarily all the work it takes to get there. Other portrayals of the gaming industry sort of glamorize the crunch aspect of making games and the sacrifices people make. Was it because that sort of thing is less interesting or less compelling television or maybe because the ideas are simply more interesting for you as creators?

I think it’s probably a combination of both. I know that there is an art to coding, absolutely. But I don’t know much about it. I do absolutely see that there’s an elegance and an art to it. But I think in a visual medium like TV and for a broad audience it’s really hard to translate that. And I think for myself personally working in a visual medium, working in a storytelling medium, something that’s a little bit more accessible like music and painting and how those ideas made it into the game they’re just easier for me to understand and translate.

Last question: is there a game you’re playing right now that’s getting you through These Trying Times? I know you’re still doing a lot of press and enjoying the fact that the series is out, but is there anything you keep coming back to?

So during lockdown, I’m locked down with my seven year old, so I had to play Roblox a lot. But I will say I think that Sayonara Wild Hearts is the best game of the last year. I think that that’s a really great escapism game. It is slanted toward music and art, which I like a lot, which I think it’s just totally immersive and wonderful as a game that’s pretty simple.