At one point during Morgan Neville‘s great documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood host Fred Rogers’s delightfully human and thoughtful confrontation with the Senate Subcommittee on Communication in 1969 is highlighted as one of the central moments in the beloved figure’s long career. Why? Because when he appeared before the subcommittee to defend public television against then-President Richard Nixon’s proposed budget cuts, he ultimately explained how important his role as a public educator of sorts was, thereby endearing himself to the Senate’s most ardent budget hounds.

It’s one of the many beautiful and raw moments in the documentary, and I bring it up today because I’ve been thinking about it a lot since news of Marvel Comics legend Stan Lee’s death broke yesterday. The 95-year-old writer, editor and publisher’s impact on comic book fans, hip-hop artists and the ever-growing Marvel Cinematic Universe is undeniable, of course, but what he did for comic books themselves deserves its own recognition. In 1971, Lee experienced his own Fred Rogers moment with the Comics Code Authority, a self-governing body tasked with policing its own industry to avoid government regulation and censorship.

Established by the Comics Magazine Association of America in 1954, the CCA was tasked with creating and enforcing the “Comics Code,” a collection of strict guidelines for comic book creators regarding what they were allowed to publish. Many of these guidelines, including the CCA’s rules regarding the depiction of criminal behavior, were questioned and later reviewed in the late 1960s and early 1970s following complaints from publishers, but drug use — despite its very real connections to the counterculture movement in the United States at the time — was out of the question.

So when the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now Health and Human Services) approached Lee and Marvel about doing a story that dealt with the horrors of drug abuse in 1971, they had to seek the CCA’s approval first. The Comics Code did not explicitly ban depictions of drugs or drug use outright, but one of its general clauses had been cited before in such instances. “All elements or techniques not specifically mentioned herein, but which are contrary to the spirit and intent of the code,” it stated, “are considered violations of good taste or decency.”

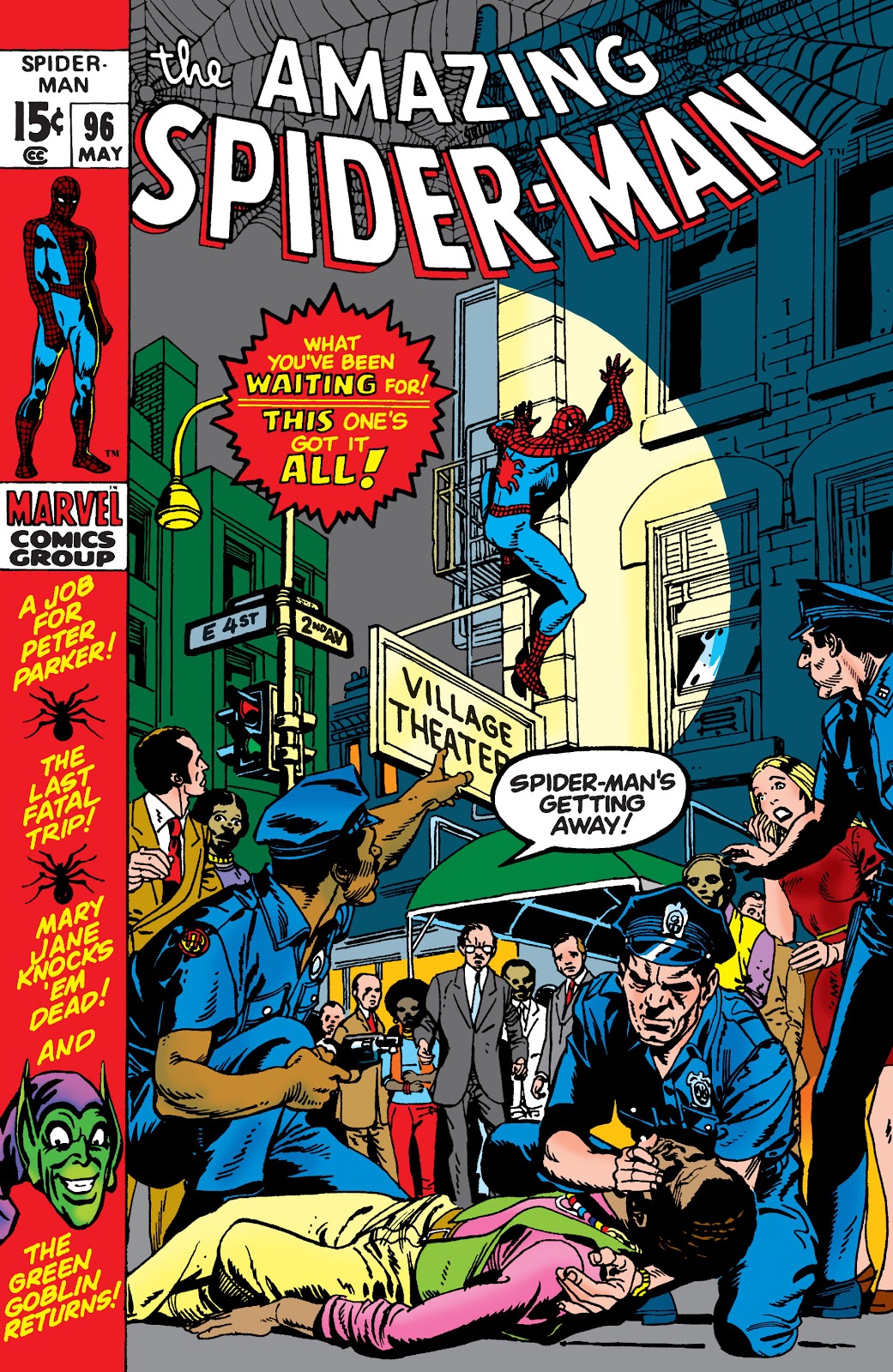

In other words, should the CCA feel that something was in violation of the Comics Code’s spirit, but not actually a part of the code itself, they could forgo granting the comic book in question their seal of approval. That’s exactly what happened, as the CCA’s acting administrator, Archie Comics publisher John L. Goldwater, decided not to grant Marvel’s three-issue drug abuse story in The Amazing Spider-Man the governing body’s seal.

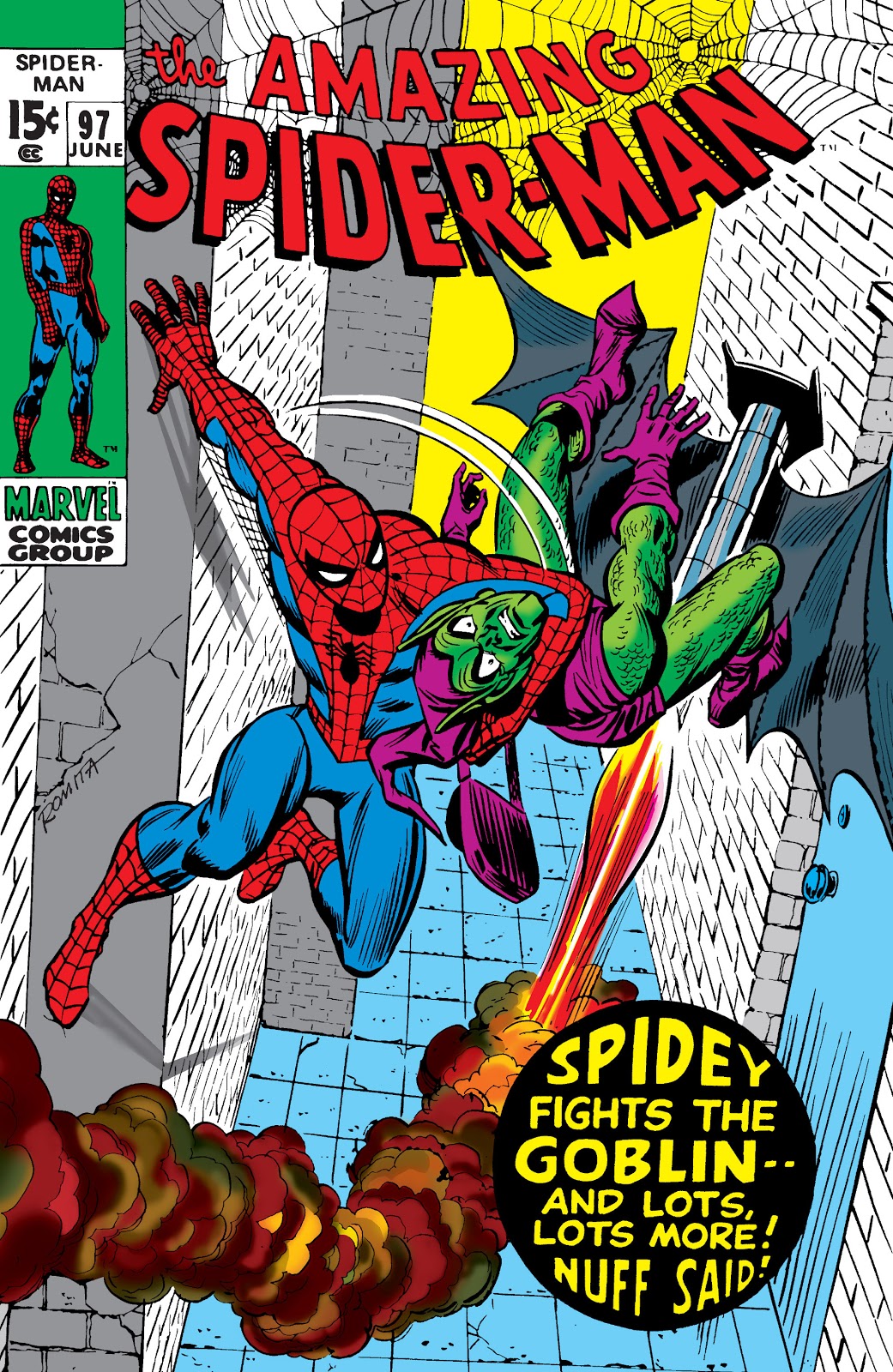

So if Lee, then Marvel’s editor-in-chief, wanted to go through with his short series about Harry Osborn’s abuse of LSD and Peter Parker’s efforts to help him, he would have to do it alone. So he did. Marvel published The Amazing Spider-Man issues #96 through #98 without the CCA’s seal, thereby ignoring the Comics Code altogether in order to tell what it thought was a good story that would click with modern readers.

In a 1998 interview with Comic Book Artist, Lee explained his reasoning for bucking the CCA and publishing the three issues without the coveted seal:

I never thought about the Code when I was writing a story, because basically I never wanted to do anything that was to my mind too violent or too sexy. I was aware that young people were reading these books, and had there not been a Code, I don’t think that I would have done the stories any differently.

He was right, too, because readers bought the issues in droves, making Spidey’s latest fight with the Green Goblin one of the character’s most popular stories ever. It proved so popular, in fact, that the CCA ultimately (and quickly) sided with Lee and Marvel’s particular approach to edgier storytelling — that is, the incorporation of darker subject matter like drug use and abuse, albeit with a moralizing tone — and incorporated its acceptance into the Comics Code.

Others quickly followed suit with similar stories, including DC Comics’ Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85 in September of that same year, which saw the latter hero’s sidekick Speedy dealing with a heroin addiction. Unlike The Amazing Spider-Man‘s treatment of the subject, DC waited until only after the CCA had finally decided to change the Comics Code so it could seek the governing body’s approval in the matter. The thing is, they never would have been able to do this had Lee, Marvel and Spider-Man himself not gently nudged the matter directly into the CCA’s purview that summer.

“I think the CCA were trying to do a good thing,” Lee said when reflecting on the episode in a 2012 Reddit AMA after being asked about his decision to publish The Amazing Spider-Man despite the group’s protestations. “They thought that only children were reading comics and they genuinely cared about what they were doing. They were mostly a pain in the neck, but we worked with them because they had good intentions.”

To be fair, the CCA wasn’t out to get comic book creators like Lee. They weren’t censoring potential stories just because they didn’t like them. Instead, they were simply trying to police themselves and avoid larger altercations with an increasingly comics-savvy public that, should the occasion call for it, might go to the authorities should their children read something out of turn. Yet this very idea of self-censorship was what Lee spoke about nixing altogether, and without his Fred Rogers-like efforts to prevent such practices from taking hold for much longer, many of the medium’s most celebrated narratives never would have happened.

Tony Stark and Carol Danvers never would have battled alcoholism as Iron Man and Captain Marvel. These heroes and others like them, faults and all, might not have ever entered the current zeitgeist they now inhabit thanks to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. And sure, the Marvel Studios versions of these characters haven’t explicitly dealt with adult-oriented topics like drug use and abuse, but who’s to say some writer or director won’t impress their importance on studio president Kevin Feige? Who’s to say he won’t follow his predecessor’s lead?