This is the storm we’re in. Liberals at war with conservatives. Left versus Right. Republicans versus Democrats. Donald Trump supporters pitted against everyone else. These conversations touch every corner of our lives. They require reason and discussion and, as hard as it is for either side to admit, some degree of nuance. They beg us to step out of our echo chambers and to understand the better arguments of those we oppose. They’re also essential to any sense of progress, at least until slicing up the United States into more manageable parts makes it onto the ballot (many empires break into segments in their dying days).

But the MAGA hat is different. The hat’s its own thing. It is imbued with a symbolism that’s divorced from complicated ideologies. The volumes it speaks aren’t about the thorny issues of immigration policy; they’re about Trump’s coarse blanket statement about “criminals and rapists.” It doesn’t represent a side of the continual battle waged over the bodily autonomy of women; it’s “grab ’em by the pussy.” It’s not connected to any piece of the important conversation about how to heal America’s racial divide, make peace with our shared past, and fight racism in the present while moving forward as a nation; it’s simply the voice saying “both sides” after Charlottesville.

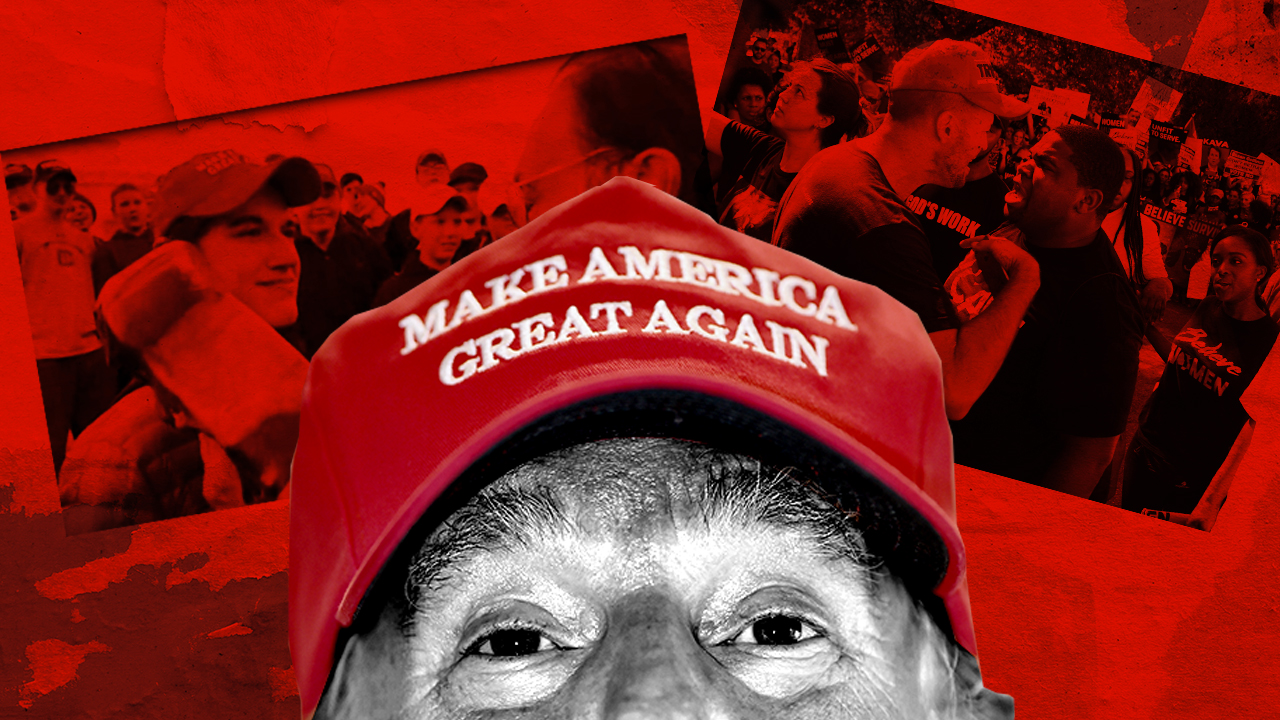

That red hat, emblazoned with the phrase “Make America Great Again” in white letters, isn’t a political statement anymore. It’s a declaration of intolerance that has taken on a life of its own. So when a few dozen smirking white kids wearing the hat have a confrontation with an Omaha elder at the Lincoln Memorial, the context added by viewing a preceding confrontation with a sect of the Hebrew Israelites becomes largely unimportant. The kids are wearing a symbol of hate. Not just a symbol of hate to adults involved in the political conversation, either. A symbol that has been linked to bullying in schools across the country.

***

Calling a cheap tourist souvenir hateful is a cloudy, dangerous accusation to level. Especially when made by a writer who aims to be progressive on political issues and, for that, is often accused of being bitterly partisan. Most of the matters dividing the country require a more thoughtful approach, not drawing lines in the sand. And painting one another as fascists or racists or bigots hardly ever serves our broader national discourse.

But it’s also true that sometimes a symbol becomes, well, more than a symbol. It gets detached from whatever intent it originally had and lends its iconography to extremism. The swastika was a Sanskrit sign that represented good fortune across Europe and Asia. But to expect the Western world to see it as anything more than hate speech is, obviously, absurd. Once a symbol is imbued with hateful meaning, it’s rarely salvageable. The Iron Cross was a German war medal far longer than it was associated with Nazism and brands have long tried to reclaim it without the racist connotations. But there it was at Charlottesville, its intended meaning undeniable. Similar attempts to reposition the Battle Flag of Northern Virginia (popularly known as the Confederate Flag) as representing some nebulous set of Southern values rather than the desire of the Confederate states to own and profit from slaves will always fail.

At some point, trying to extract the hate from a symbol best known for hate just leads to flailing mental gymnastics. Whereas for the non-racist, rejecting a symbol that connotes racism to those facing the actual discrimination takes no effort at all. It’s racist? I won’t wear it! Done!

The MAGA hat has entered mental gymnastics territory. You can suggest that it refers to the broader ideology of all of Trump’s constituents, but to do that discounts complex, often warring, desires of the various groups who voted for Trump (many against their own best interests). The hat isn’t Libertarians taking a flyer on him because they believe America intervenes too often in the affairs of other nations. It’s not poor whites tricked into thinking they’re fighting on behalf of our country’s 50,000 coal workers (0.0153% of our populace). It’s not conservative Christians who have stayed loyal to the Trump White House on the basis of abortion alone, even when his personal choices seems to directly mock their ideology. And it’s not the rich looking for a president who will help them capture and protect immense amounts of wealth.

You can call all of those voters racist, for how they ignored the rhetoric of Trump the candidate. And if you’re talking about the covert, cloistered racism that has poisoned our nation for so long, you could make a hell of a case. But you’d have to make a case. You’d have to explain to someone who voted for Trump why that, in itself, is an act of bigotry.

The same doesn’t go for the hat. The hat is ready to be generalized about. The hat is PrejudiceWear™. It’s not connected to any sort of conservative value. It doesn’t speak to your feelings on social programs or tax code. It’s moved on past any degree of uncertainty. It’s a marker of Trump’s vision of white supremacy. No matter who wears it.

If anyone knows how difficult it is to reposition a symbol as something else entirely, it’s Kanye West. The hat that made him feel like Superman has made scores of less powerful people feel threatened. His attempts to overwhelm those feelings of dread among the marginalized with his own force of personality (which is undeniably immense) have largely failed. He’s fumbled, been called out, and had to restate his feelings on the matter, only to fumble again. You can see that when his closest ally in hip-hop, Pusha T, calls the hat this generation’s Klan hood at the same time his boss is defending its virtues.

You may not go so far as Push. But in the end, the hat is defined by the very words it uses, harkening back to some mysterious time when America was great. Which, by its nature, implies great for whites. Because minorities, women, and the LGBTQI faced measurably more inequality back in the “good old days.” They were just left voiceless back then.

People wearing the hat seem to proclaim, “That era was great for me! Let’s return to it!” Which is to say, “I liked not knowing about how shitty things were for some people!” And that implication, which really doesn’t take much reading into or stretch the layperson’s understanding of symbols very far, is hateful to the core. It’s a gross denial of the experience of others.

In his statement to the press, the student at the heart of the confrontation at the Lincoln Memorial professed deep reverence for his elders and veterans (of which Omaha tribal elder Nathan Phillips, who he confronted, is both). But if that was his intent, then he should have taken his hat off. Even if he bought it on a lark. Even if he feels like adults are taking this whole hat thing too seriously.

Because the motto he wore that day spoke volumes. It was an implied insult. It cosigned hate.