One of the underrated tragedies of a loved one dying is not knowing how best to honor them. How do you sum up a whole life in one eulogy or memorial service? And once that’s over, then what? What does the act of remembering require of us?

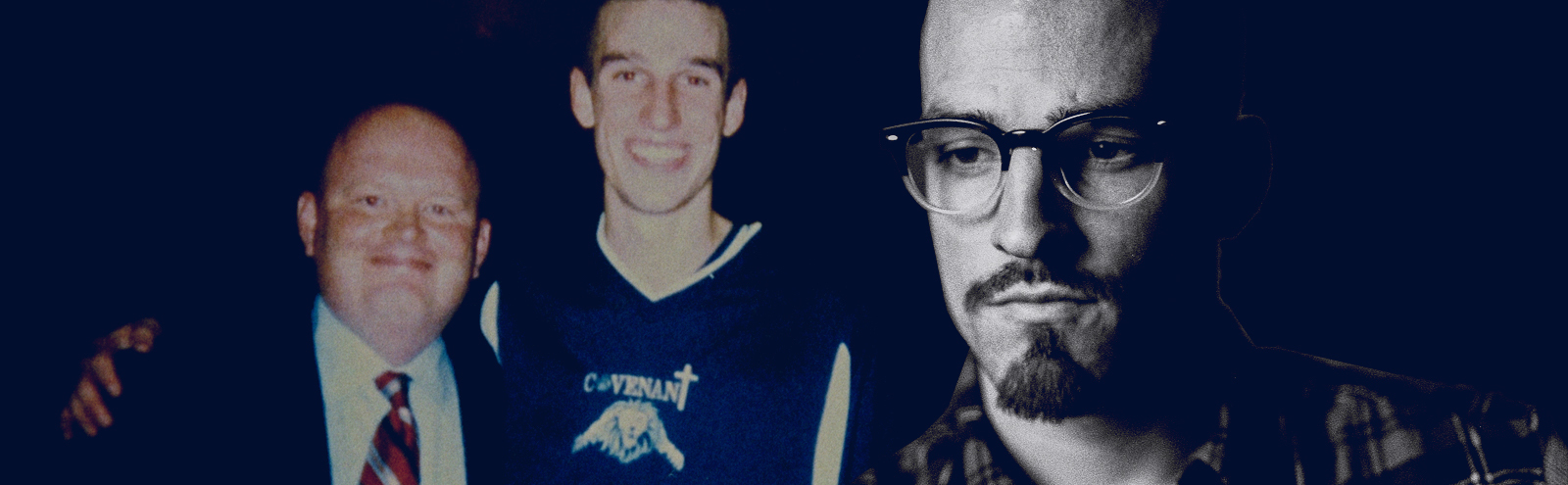

For Justin Robinson, whose older brother Jordan died young from an aggressive form of cancer, remembering his brother required devoting eight years of his life to an entire self-produced and self-financed documentary, My Brother Jordan. He released it himself, for free, on his unmonetized personal YouTube page at the end of August, because, he says, “It was free to be Jordan’s brother.” My Brother Jordan has since received more than 7 million views, without benefit of distributor or ad campaign.

My Brother Jordan is sort of the ultimate “labor of love.” After various distributors told Justin — for whom film is also a day job, working in the camera department on various productions — that his film was “too personal,” or too narrow in scope for a mass audience, he chose to just put it out into the world rather than change anything. It was more a necessary part of his own process in making sense of it all than something he hoped would make him a famous documentarian.

That My Brother Jordan has become something of a phenomenon all on its own seems to prove that the business world’s predictions of audience taste at best lag behind actual audience taste. Just this month Netflix released Dick Johnson is Dead, another extremely personal documentary directed by a professional camera person about a loved one’s mortality, to widespread acclaim (it’s currently 100% on RottenTomatoes, with some critics calling it their favorite film of the year). To be sure, My Brother Jordan is probably a few degrees more personal than that, but no less an achievement — a 63-minute distillation of eight years, 102 interviews, more than 300 videotapes, and 450+ hours of total footage.

Maybe, paradoxically, the way to achieve true universality is by not skimping on the details. Justin and Jordan, who also have two older brothers, come from a family of home-schooled pastor’s kids, the kind of family that banned the screening of PG-rated movies until the kids were in their teens. It’s a milieu that, as someone who grew up around a fair amount of devoutly religious people myself, frankly has always skeeved me out a bit. But Justin, whose two older brothers are now pastors themselves, spares neither the self-deprecation (at one point he freeze frames the old home movies to diagram “the official home-schooled kid’s haircut”) nor downplays the Jesus talk. It comes off as a person simply being honest about their upbringing, something more directors should strive for.

From a certain perspective, it could be the ideal soft sell, a movie with faith as a theme that doesn’t go in for the usual culture war stuff. Yet even with contacts in the faith-based film community, Justin says the word on the street was that My Brother Jordan didn’t sell hard enough, wasn’t traditionally “uplifting” enough for the “faith-based” film community to rally behind.

It’s good for the world that Justin Robinson didn’t compromise his vision. If My Brother Jordan is too personal, too narrow, shares too much… well that’s kind of the whole point, isn’t it? Without that, it wouldn’t make sense that Justin had done all this. He goes damn near to the ends of the Earth just to give his brother the posthumous gift of a fully-formed remembrance. You don’t have to know the Robinsons personally to be touched by the gesture.

—

Can you run through how long it took and everything you went through to put this whole project together?

My oldest two brothers, we’re not as tight as me and Jordan were, the age difference or whatever, but for whatever reason [Jordan and I] were like scientifically melded. Growing up, we did everything together. It was never the thing where the older brother hung out with the older friends and the younger brother was kicked out. We all shared the same friends. Then he moved away his freshman year of college to go play college basketball. When we came and visited him and he got cancer, 13 months later he died. And he had been dying for months and so it wasn’t necessarily a surprise, but… I mean, every death is original. No one dies in the same way and no one has the same family dynamics.

As a person who wanted to tell stories, this was the ultimate story because it was not just his story, it’s also my story. And when he died, I knew that I was going to tell his story in some way. I was pretty young and green in my filmmaking knowledge then, but I knew enough to shoot interviews and so it took me four years later after he died when I was a senior in college to start out on this journey.

I started in Florida, which was kind of the golden years of our relationship, but I started there and interviewed almost 35 or something people within a week. All my friends, coaches — just trying to gather as much information like a detective. And then a few years went by and then I started to feel like it was time to dig in and take it to the finish line, which I knew would be a year. So I started saying no to things. I’m freelance, I work in a camera department on movies here and there, and saying no to jobs as a freelancer, that’s not the greatest thing to do for money.

But I knew that it was the time so I started digitizing all these tapes and then really got invested. I ended up just driving to all these other states that we used to live, because we moved around a lot, and just started doing everything. I think someone asked me a question the other day, like, “What was the budget? What was the production company?” I’m like, I put gas in the car and drove to the story. There was no one behind me, I just kept doing it and kept at it.

The quantity was the biggest thing. There was so much footage and we had to go get the medical documents and get those released. There’s 1200 pages just of medical documents. I had to spend time going over those just to get it right chronologically to write the documentary’s voiceover. “Okay, this is July, in 2007. This is August and this surgery happened here…” It was massive. I lived in Dallas for almost two years of the main portion I was doing this and people would say, “How’s Dallas?” And I’m like, “I don’t know, I haven’t really left my apartment.”

And then how long between final edit and release?

I locked the edit in August 30th, 2018. So it took two years to get the color and the music. Everything was a journey, peaks and valleys of people coming in and working for free. And then my basketball coach who was close to me and Jordan, he randomly died of a heart attack, as you see in the documentary. That was a new challenge. He would have been the first person to see the full documentary. That kind of accelerated things, like “I got to finish this before someone else dies.” So much life had happened. I had out lived my brother. I’m older than he ever was by a long shot now, so I don’t know, it was just something that I was doing for myself. And then I wanted to screen it with friends, but the COVID hit, and that kind of became an ally in a sense. Because it’s a very personal watch. If you were seeing that publicly, maybe the world might not have been more open to the empathetic film that it is. So in a way with the year, I think everybody kind of needed a good cry in some way. I tried to kind of shop it to see if I could get it on streaming services anywhere and then people said, “It’s too personal, it’s not universal and you might have to cut some stuff. You might need to cut your coach out of it.” And I’m like, “No, I’m not going to do that.”

I assume you had basically finished it and then approached people to see about releasing it?

Yeah. I don’t have an agent or someone to sell it, but it was basically just colleagues in the industry that had connections or could’ve passed it along. And so January 8th, almost on the eight year mark of start to finish, I finished it. I started messaging around all year. And then COVID hit, which made it weirder for people to even take time to watch. And [they’d say things like] “I don’t know, it’s too personal. Maybe if you really knew him, it’ll be really great, but since you don’t know him, he’s not famous…” Like the classic things that you kind of assume going in.

There was one possible thing with maybe Vudu, they were like, “Maybe Vudu would buy it.” But I knew in the back of my mind that on August 19th it would mark 12 years of Jordan being dead, so I said internally, I’m just going to release it myself for free. Because, I mean, if you watch a movie and it’s $2, there’s going to be a pause of like, “Is it worth it?” Or is it worth the 20 seconds of typing in your debit card? I wanted to do it for free to eliminate everything so that all you have to do is click. And my YouTube channel is not monetized, so there are no ads. It won’t pause your viewing experience. It was free for me to be Jordan’s brother and it’s not free to make this, but I wanted it to be as free as possible in every sense of the word, financially and just available.

What’s the response been like now? I mean, you’ve had a lot of organic traffic to it now.

I mean, it was definitely surprising. It’s been [a big thing for] people that know me and people that knew Jordan for a long time because they had known [about this movie] for eight years. So I knew I had that momentum going for me. In the first two weeks, I felt like every person I’ve ever met shared it. And for the first time ever I had asked people like, “Hey, if you really dig this, it really does help to share it.” And it had like 20,000 views on YouTube and I thought, “Wow, this is kind of what I thought it would be like at the end of its life,” because I don’t have a big YouTube or Vimeo following.

And then it was about that 20,000 mark, it was like a Monday, then the next two days, it was just 40,000 more, 50,000 more, then a hundred thousand. People were leaving comments saying, “It’s on my algorithm. It just showed up on my page,” in New Zealand and Australia and the Philippines. And then people started sending me screenshots of TikTok videos, and it was like a bunch of 15-year-old girls crying watching the doc. It was like a reaction hashtag thing. That was new to me. Then it blew up on TikTok, so it was the wave of TikTok and the wave of the YouTube algorithm and then people were sharing it and it was on Reddit apparently. Then it just kept going. So at this point, it’s slowed down a little bit…and now it’s about to hit 7 million views. So it’s above and beyond my wildest dreams. But at the same time, it’s all cherries on top because I made it for me and the people that knew him. If you, a stranger, can see it and enjoy it, that’s awesome. It’s made for everybody, but I started making it for me.

Has anybody reached out that wants to distribute it now that they can see that there is a viewing market for it?

There was one group of people that talked about it and I haven’t heard. And they were just really interested when it hit a million views. I think that sets off big alarm bells for lots of people. So I don’t know if that’s going to lead to anything and then I’ve gotten a few emails from smaller things that sound shady, but nothing legitimate.

When you talk about doing it for yourself and when you finished it, it seems to me like that would be kind of like catharsis, like a chapter closed. Is it hard to have to talk about it all over again now that people want to interview you about it or you have to pitch it to someone who wants to distribute it or whatever, now that you’ve put like a decade into it already?

For me, not at all. A lot of the interview process was me kind of sharing my own heart. I drove a thousand miles to talk about him. I know there’s not a big vocabulary for death or grief. There’s like, “I’m sorry for your loss. I know how you feel. He lost the battle to cancer.” No one really expands on that. So for me, I was like, hey, I’m an open book. Jordan was the greatest person I’ve ever met. Not just because he was my brother, but I’m here to talk about him. I think he’s one of those people that falls into the genre of just the very simple, kind person that does something for no credit. And so in some ways, I wanted to give him the credit, but also tattoo this whole thing into my memory, [so that it will be there even] if I get old or forgetful one day. These were the glory days of my life thus far. So for me now, it’s not hard at all. It’s a joy to talk about him and to share.

So you guys were pastor’s kids. Are all your brothers pastors now?

My two oldest brothers are both pastors in Florida and then my dad is a retired Southern Baptist pastor.

And you’re still working in film production?

Not enough, but yeah. I’m not a pastor.

Do you think of this as a Christian movie?

No.

Do you think there’s…

No, just short answer, no. There was a pretty big acquaintance, colleague, friend who’s big in the Christian film world as a camera assistant or a camera operator. I’ve worked on a lot of the faith-based films, like some of the Christian movies and the ending [of My Brother Jordan] was not happy enough. There was a rebuttal that it was not ready to come out of the oven, so to speak. It was an interesting perspective from that genre and that audience because that’s the genre I grew up with and still see from time to time. I don’t picture it as a Christian movie. I have a handful of feature scripts I’ve written that fall within a backdrop of Southern religious culture that deal with that because a lot of those cultures are very cinematic. I don’t know if you grew up in church, but if you’ve ever heard of a country Baptist church potluck where they have a meal after the service, I mean, that’s some of the most cinematic things that you could ever photograph on film in a weird way. The things I grew up with are very interesting to me cinematically, but none of those I would consider Christian films. Even if I said it was a Christian film, someone would say, “No, it’s not,” or “It’s not Christian enough.” Even if God made a cameo, I think they’d probably say it’s not.

I was wondering that because I could see someone wanting to sell it as a Christian film. Do you think it’s because it doesn’t sell Christianity enough, is that why it wouldn’t work as that?

I think that was the gist of the email I got, was that it needs to sell it at the end, but I’m not a salesman — I’m a filmmaker. So yeah, I’m sure that that would be the goal for a lot of people, but the story is the story and the ending is never what people want — usually in life or in movies. I’m kind of okay with the endings that happen in life, as tragic as this one is.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.