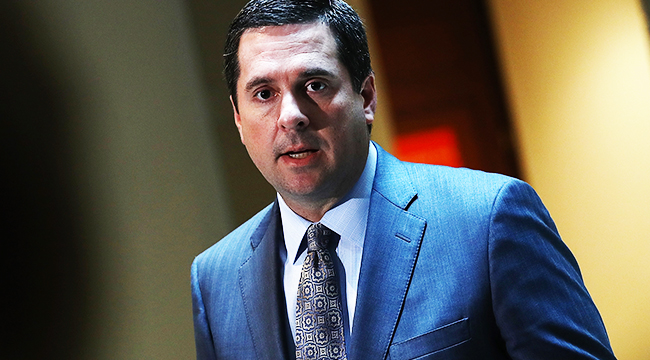

All of Washington has been consumed by Devin Nunes’ ever-changing memo alleging “bias” at the FBI and information it gathered that later may have become part of the probe into possible Russian interference with American elections. The memo claims that information in the Steele dossier was the tipping point, so to speak, in FISA warrants being issued and renewed for shifty Trump saga bit player Carter Page. Nunes’ argument is that because some of the data Steele gathered was paid for by the Democratic Party, and due to Steele’s alleged bias against Trump, that means Steele is not credible and the process was unduly influenced.

But the “proper justification” for a FISA warrant doesn’t have to be nearly as dramatic, and Nunes stops short of accusing any government agency of violating the law. That’s because even if Nunes’ memo is completely accurate, and that’s already highly disputed, it’s unlikely any of it would be illegal. FISA has been controversial for years because, thanks in part to laws passed by Republicans, nearly anybody can be the subject of a FISA warrant, for almost any reason:

- As the name implies, FISA is about monitoring foreign citizens and agents of foreign powers: Passed in 1978 in response to the abuses of power by Richard Nixon, FISA was designed to clearly separate surveillance of American citizens for surveillance of foreign nationals. It created the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, or FISC, and that court was tasked with the job of approving surveillance warrants. This is to prevent Nixonian tactics like ordering FBI agents to monitor political opponents. For security reasons, FISA warrants and the cases around them are highly classified and not available to the public.

- FISA was obscure outside the intelligence community until 2006: Starting in the Bush administration, Republicans in particular have greatly expanded the powers under FISA. In 2007, George W. Bush signed the Protect America Act into law, which allowed the U.S. to monitor foreign citizens without a warrant. In other words, if you sent an email to your buddy in Japan, and the government thought your buddy might be a terrorist, they could read that email. The law was made so broad that in 2013, Edward Snowden revealed that a FISA warrant had allowed the NSA to collect call data on Americans for years.

- FISA warrants operate on reasonable suspicion, not concrete proof: The FBI doesn’t have to prove somebody is a spy or a criminal to get a FISA warrant. Instead, they have to prove they have a reasonable suspicion somebody is an agent of a foreign power, which is not just spies and terrorists, but also anybody who aids and abets them, even unknowingly.

- Furthermore, personal motivation on anybody’s part doesn’t matter much in these scenarios: Unsurprisingly, people report criminals to the police for all sorts of reasons, from the noble to the petty, but the courts have ruled repeatedly that omissions only matter if they would have materially affected the judge’s decision. Personal motivation rarely rises to that level, even in some of the most extreme cases exploring this territory. Not helping matters is that it’s easy to confirm details of the dossier independently. In fact, Carter Page himself did so under oath, to the House Intelligence Committee, which is chaired by Devin Nunes.

Is it possible that Page is just in the wrong place at the wrong time? It’s certainly within the realm of possibility. Whether U.S. interests are best served by erring on the side of surveilling everyone is certainly a discussion Americans should be having. But the argument of the memo itself seems to misunderstand how these cases are handled. Like or dislike of Trump is irrelevant to the courts. What matters are the facts.