Ah, beer. Homer Simpson once toasted with a mug of the sudsy elixir and proclaimed that alcohol was the “cause of and solution to all of life’s problems.” Wise words, Homer. Wise words indeed. Alcohol is a such a varied and vast set of liquids on a macro level. There’s a lot of real estate between the world of Italian wines and bourbon, for example. And that’s before even talking about the separate ecosystem of beer. Which is simply to say, there’s a lot to know about what you drink. Plenty of sticking points and opportunities for confusion.

Today, we’re looking at the often-obscured differences between stouts and porters. The dark ales are strikingly similar in taste, texture, aroma, and endgame (they get ya’ drunk). So we asked our beer sherpa Joe Stange — co-author of the Good Beer Guide Belgium — to break down the difference between the styles. “If you look at a Venn diagram of stouts and porters,” Stange says, “you’d be looking at a single circle.” Basically, the two are almost identical as far as beer and drinking beer is concerned.

Some beer drinkers, brewer’s associations, and clubs do judge the styles as separate entities, which only compounds the confusion. So let’s dive in and take a look at two shockingly similar beers styles with two different names. But before we dive in, let’s get this out of the way: We’re talking about standard porters and stouts here. Both styles come in “Imperial” variations that equate to aging and higher ABVs. This piece is focused on the basic styles, not the variations on a theme via smoke, oats, milk, and geographic designations like the Baltic.

Cool? Okay, let’s dive into the black stuff.

A LITTLE HISTORY

The style of beer that would today be called a porter or a stout goes back to England in the 1700s. The myth goes that during those days, porters would head down to the pub after a day of porting heavy shit around the London docks and get tipsy. They’d often order a mix of light and dark beers from the various casks on tap that day. It was called ‘threading’ and allowed them to cut heavier, higher ABV beers with lighter, more palatable beers. Think of it like all those times you took a little soda from every tap at the self-serve soda fountain.

The barmen of the day realized that the porters were doing this to amp up the taste and ABVs of the lighter ales. So sometime around 1720, they started brewing a stronger dark ale with malted barley and a little hop. It was the compromise between the multiple styles that meant porters could order from a single cask and be happy. The Porter ale was born.

As the 1800s rolled around, things got interesting for porters and confusing for us. The ale was hugely popular. People’s taste was changing and they wanted stronger porters to take the edge off of the drudgery of life in 1800. Stronger and stronger porters were being brewed and to differentiate, the English publicans started calling the strong stuff “Stout Porter” because stout means big and strong. If you look back at Guinness’ history, you’ll find that everyone’s favorite stout was actually labeled as an ‘extra stout porter’ back in the day.

You must be thinking, “stout is just a strong porter then, right?” Ugh, we wish it were that easy.

SO WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE AGAIN?

Fast forward to 2018. Porters and Stouts are two different beer styles that can taste almost identical. A major difference today between the two is that stouts are often nitro’d (N2 is added during the pour) to smooth them out and really amp up the creaminess. For reasons best left to the murky annals of history, we don’t traditionally do this with porters. This makes the two beer styles feel different. But, if you pour a standard stout sans nitrogen next to a standard porter, you’ll be hard-pressed to notice a difference.

Nitro aside, between 1800 and today stouts became a more “sessionable” ale — that is, lower in ABVs — while porters stabilized around the five to seven percent ABV. These days you might find stronger porters than stouts at one brewery and it might be flip-flopped at the next. It’s really a matter for each brewer and the previous designations are out the window. This obviously adds significantly to the confusion.

The most notable difference between the two, at this point, is the recipe. Porters are generally made with roasted malted barley, yeast, hops, and local water. Stouts are generally made with roasted barley and roasted malts, yeast, hops, and local water. What’s the difference between “malted” and “roasted” barley you ask? Malting barley means that the grains are soaked in water until germination starts, making the starches accessible. Then those grains are dried to halt the seed from turning into a plant. Roasting barley skips this step and heats the grains directly, making the starch accessible without malting.

Those starches are then turned into sugars via the mash process and yeasts are added to eat the sugars and create alcohol. Here’s the kicker though, the starch extraction from the roasting and malting process is the same.

So, yes, there’s a difference in the recipe of a porter and stout, but only barely (it’s in the barley!). The end result is still often close to identical (chocolately, smooth) and comes down to the brewers tinkering in their brewhouses. Bill Manley over at Sierra Nevada Brewing told Draft Magazine recently that “many brewers market beers as either ‘stout’ or ‘porter’ based on their personal preferences and perspectives rather than a notable stylistic difference.” Translation, the brewers decide on the spot whether to call it a porter or stout and can call the brew either.

Luke Purcell over at Great Lakes Brewing mirrored Joe Stange’s synopsis when he told Craft Brewing Business magazine about the difference between the styles. “You can ask any number of brewers this question and get just as many different answers,” Purcell said. “The simple answer is that there really is no difference between the two.”

All of this aside, we live in a world where the two beer styles exist side-by-side and are judged separately at beer competitions. And because of this, collectives like the Brewer’s Association had to come up with guidelines for judges to differentiate between the two. So let’s look at what they were able to isolate.

STOUTS

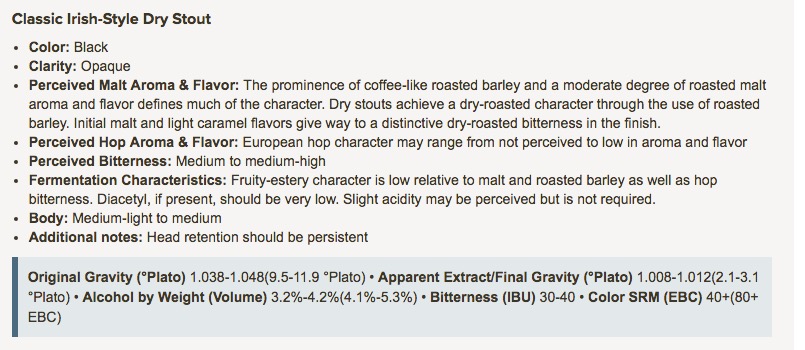

According to the Brewer’s Association, an American Stout is, of course, supposed to be black in color. The malt aroma and flavors are supposed to be of roasted coffee, caramel, chocolate with a “dry-roasted bitterness.” A little acidity is allowed.

The hop aroma and flavor is generally medium to high with a low fruitiness. IBUs (bitterness units) should hover between 35-60 and ABV tends to be around 4.5 to 6.4 percent.

PORTERS

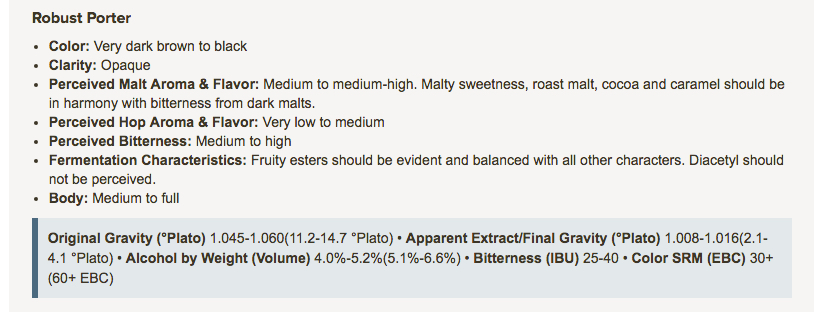

Porters can be “very dark brown to black.” This means that you could, conceivably, shine your phone’s flashlight through the glass and some light might make it through. The malt flavors and aroma are, wait for it, coffee, caramel, and cocoa. If you want to have the worst beer conversation of your life, have a beer geek try and justify the difference between “cocoa” and “chocolate” as a taste in beer.

The hop aroma and flavors should be low to medium with a little fruiti… You know what? They’re the same damn thing! It would take a damn beer savant to pick them apart!

Can we leave it at that and just enjoy a nice glass of beer?