Unlike when I first backpacked across Asia for two years on a shoestring budget a quarter of a century ago, 2022 sees a historically unprecedented wealth of useful travel information online (hey, like the Uproxx Fall Travel Hot List!). Too often, however, these travel resources focus on where to go and what to see, but not how to best attune yourself to the life-altering experiences that flow out of engaged journeys.

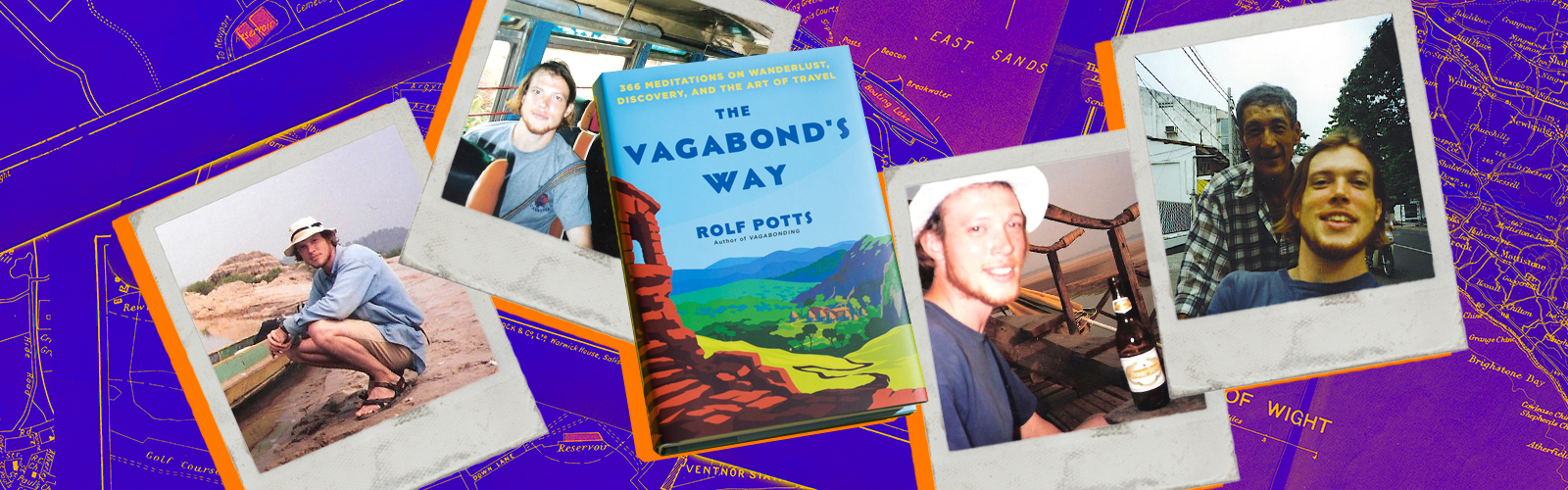

My new book, The Vagabond’s Way, was designed to inspire the reader into embracing the richer textures of travel from the initial process of dreaming and planning the journey; to the act of adjusting to life (and expanding your comfort zone) on the road; to coming full circle, and seeing your home as an intriguing new destination.

Here are three key bits of travel advice, taken from the book’s pages, that can help enrich your next journey.

1. Saving Money On The Road Is A Matter Of Attitude

In his book Libyan Sands, English explorer Ralph Bagnold posited that being able to travel long-term was less a matter of wealth than of attitude. “There are two kinds of travelers,” he wrote, “the Comfortable Voyager, round whom a cloud of voracious expenses hums all the time, and the man who shifts for himself and enjoys little discomforts as a change from life’s routine. Both may enjoy themselves, but the latter sees more of the country and its people, and has the added pleasure of going where lack of comfort excludes the former.”

Nearly a century later, Bagnold’s observation still holds true, particularly since so much of what tourists pay for on the road (particularly what they pay for in advance) involves amenities and efficiencies that can insulate them from the very cultures they’re trying to experience. Indeed, for all the perks offered by luxury hotels and tourist-district restaurants, sleeping in locally-owned guesthouses and dining on street food is not just cheaper, it’s far more likely to embed travelers in the daily life of their destination.

On the road, rich journeys don’t flow from extravagant budgets. They are found in forgoing the comforts and conveniences we’ve been told we want, and using what money we have to embrace what a place offers us.

2. Looking For Local Crowds Beats “Crowdsourcing”

Some years ago while visiting the Indonesian city of Bukittinggi, I decided to seek out rendang, a local dish consisting of slow-cooked meat caramelized in coconut milk and spices. Using the Wi-Fi connection in my guesthouse, I found a TripAdvisor review with a header along the lines of, “Best rendang in Bukittinggi!!!” The place was just a five-minute walk from where I was staying, so I decided to go.

As it happened, the TripAdvisor-approved rendang restaurant was empty when I arrived. The owner opened the kitchen for me, apologetically explaining that she usually catered to the tourist bus trade and that she hadn’t expected the buses to arrive until later that evening.

Her rendang tasted okay if a bit dry. When I left, I was still her only customer. On the walk home, I noticed something I’d overlooked on the way to the TripAdvisor-sanctioned restaurant, the street that led back to my guesthouse was lined with food tents packed with local diners. Somehow, I had completely overlooked a local street-food scene that had attracted throngs of Bukittinggi locals at the very hour my internet-approved restaurant sat empty. Had I simply used my eyes and my nose (rather than an online review), I no doubt would have had a more enjoyable meal.

This experience thus taught me a simple but elegant travel lesson. If you’re going to crowdsource an eating recommendation, the virtual advice of bygone travelers counts far less than the presence of a real-life crowd.

3. Sitting Still In A Place Can Be A Great Travel Strategy

I’ve been teaching a creative writing workshop in Paris each summer since the mid-2000s, and over the years I’ve hosted dozens of American friends in the city. Though my guests always enjoy themselves, I’ve found that first-time visitors in particular suffer anxiety when they dine at the storied brasseries and cafés in the French capital. Eager to get out and see the sights of the city, they become exasperated at how unhurried the waitstaff is in taking their order, bringing out their food, and in presenting them with their bill. This lunchtime procedure, which can be accomplished in well under thirty minutes in American establishments, can stretch across hours in a place like Paris.

I’ll admit I also felt irritation at the unconcerned tempo of French dining my first few summers in Paris. What I eventually came to learn was that the leisurely pace of brasseries and cafés was a far more genuine evocation of Paris. In France, a lunch that stretched out across three hours didn’t compromise one’s ability to experience the city, it was the experience of the city.

Often in our travels, the best way to appreciate a place isn’t to hurry off on an itemized sightseeing agenda but to first slow down. It’s to sit still for a few hours and let the place reveal itself through its own rhythms and rituals.