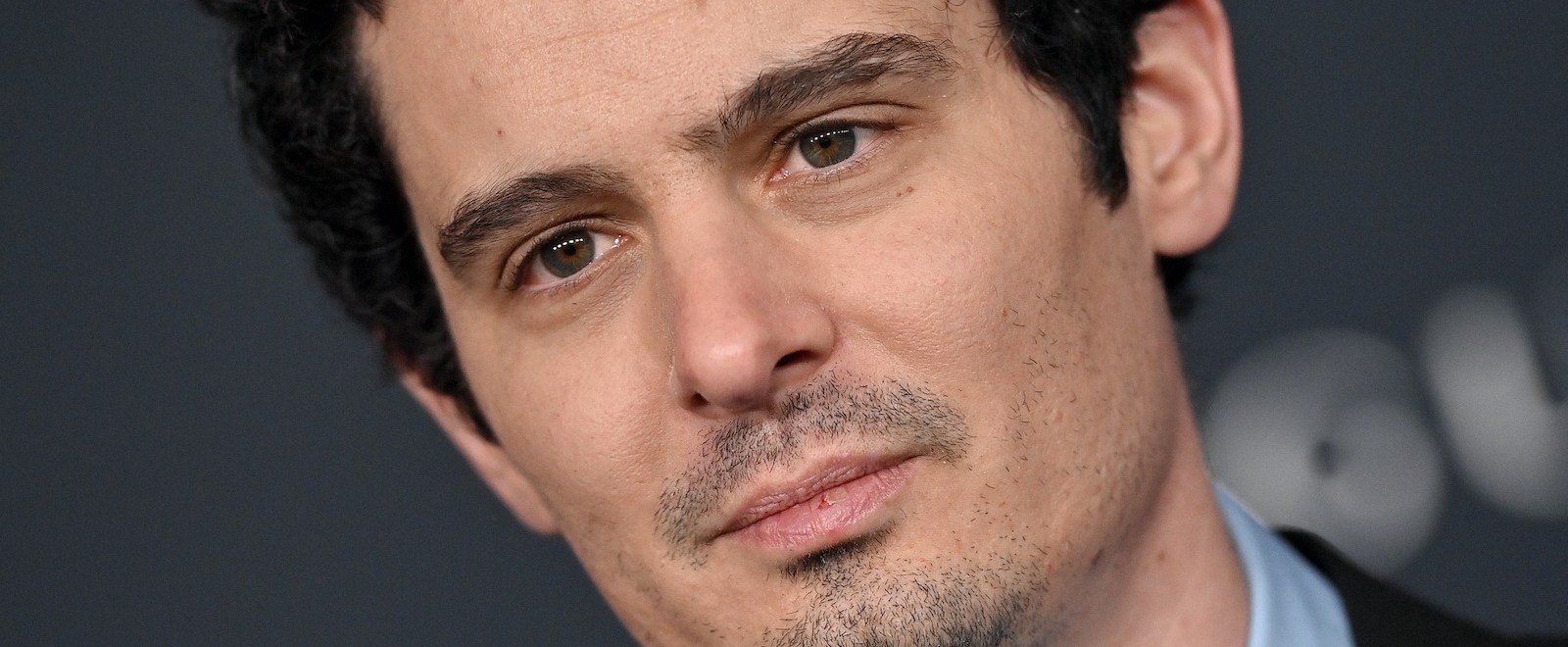

When I mentioned to Damiem Chazelle that he has referred to his new film, Babylon, as a hate letter to Hollywood, he was quick to correct that he said it is a hate letter and love letter, but then did concede there is a lot of anger in this movie. And that’s what’s fascinating about it, because for anyone who thinks they know what kind of movie Damien Chazelle makes, they will most likely be pretty surprised by Babylon. To put it bluntly, Babylon is very much not La La Land.

Set in the 1920s silent film era, Babylon whisks us around an assortment of characters – played by Margot Robbie, Brad Pitt, Jovan Adepo, Jean Smart, and Diego Calva to name a few – as they try to navigate what seems like at times, a lavishly excessive place, and at other times, a mostly terrible place.

But I’m mostly interested in why Chazelle – who I met professionally eight years ago and I’ve come to know as a very thoughtful filmmaker who doesn’t really put stuff out there without something to say – made this now. To his point, he has been writing Babylon since 2008, but I couldn’t help but think about his last two movies. In 2016, La La Land, a true love letter to Hollywood, was the darling of the film festival circuit, that is until a good number of film reporters turned on it. (Chazelle did become the youngest director to win the Oscar for Best Director that year.) Then in 2018 First Man, a true love letter to space exploration and human drive in the face of adversity, didn’t even get a Best Picture nomination in a year that Green Book won Best Picture. Now here comes Babylon, a movie about how (1920s) Hollywood isn’t so great. Was Chazelle feeling a need to say, if you think you have me figured out, think again? I posed this exact question to Chazelle.

But, first, when I spoke to Chazelle, I had to race home during a rainstorm from a screening of Avatar: The Way of Water and you can judge for yourself if this first exchange is a joke or not…

This is the second movie I’ve seen this year with the Na’vi in it.

Yeah. You didn’t expect that, did you?

Your movie is spoiler-proof. People who say, “No, don’t tell me how it ends.” I say the Na’vi show up and they’re like, “Okay, sure, asshole.”

That’s great. Yeah, you can just have fun with that. “All right. Whatever, Mike.”

So, I feel like there’s something on your mind with this movie. It seems very pointed. You’ve called it a “hate letter to Hollywood.”

A hate letter? No. I think I called it a “hate letter and a love letter.” Or “a love/hate letter.” I think, well, yeah, on the dark side of the ledger, I sort of did feel, especially after something like La La Land, it felt like I had this sort of desire to try to really get at the darker underbelly of Hollywood. Which I think is just as much a part of the whole equation, to borrow that phrase, and to try to paint a portrait a little bit of the machine of Hollywood as an overall entity. So it’s bigger than any one person. It’s this sort of machine that was built by humans but kind of wound up very quickly dwarfing them, and it swallows humans up and chews them up and extracts their souls and spits them out and then moves on to the next generation. And that’s kind of horrific.

And yet, somehow, out of that kind of merciless, voracious sort of cycle of destruction, these kinds of beautiful pieces of art sometimes emerge as though from the sky as though dropped by angels. And I think there’s no better manifestation of that really than the silent era. When, to me, the highs of the art form were higher than they’ve ever been probably. And the lows of what people had to do, or chose to do, behind the scenes, in some cases, were maybe never as low or as extreme or as horrific as they were.

As you said, these beautiful things were made, and you’re very clear about that at the end. But it also does feel like an eff you. It feels like you’re mad about something. Your past movies have a level of aspiration in all of them. And this one, there’s some of that, too, but not on a positive side. Babylon, it’s angry. It just feels so different than your other movies. And I feel like that’s on purpose.

Yeah, I think it’s certainly more brutal than the other movies. I don’t know. I felt Whiplash was pretty angry, too. I wouldn’t say that it’s any angrier than Whiplash, but certainly angrier than La La Land or First Man.

But Whiplash still has that notion of, “We have to be the best.” Even though those are very flawed characters, they kind of find that at the end, and these two people can have each other for that moment.

I would just debate with Whiplash whether that’s a good thing, that they wind up kind of simpatico at the end, given what we know about the characters.

Oh, I’m not even saying that’s a good thing, but there is that level of aspiring throughout that movie.

I guess I would say I find a lot more hope in the ending, or where this movie winds up, than in where Whiplash winds up.

I do agree the ending of Babylon ends on a positive note. But it’s very different than your other movies, and I feel like that was by design. In a, “You think you have me figured out? No, you don’t. Here’s this,” way.

Yeah. I think again, there probably was a little bit of… It’s something about how old Hollywood is treated so often that I do think I’ve sort of even just subconsciously maybe reacted against. Which is that there is this sort of tendency to romanticize and, to some extent, whitewash. But you could say, even just more broadly, just sort of sanitize and clean up. It’s sort of doing Hollywood’s job for it. You know what I mean?

How so?

Where Hollywood, of course, is very, very skilled at refining and telling its own story. And obfuscating reality and hiding things under the rug. But it just feels a lot of times the sort of depictions of old Hollywood sort of play that same game. Even if they’re showing stuff they would consider naughty behavior, it’s always with quotation marks. There still is a quaintness. And there was just nothing quaint about this time.

And I think you could argue it is sort of hard to say that there’s ever been anything really quaint about Hollywood. It doesn’t feel quaint to the people whose lives truly do get ruined by the machine of it. And that’s whether it’s in the ’20s or the ’30s or today. So I think if there was any anger, it was more just maybe a subconscious reaction to certain kinds of depictions or myth-making that I’d seen before that just it felt like it was time to take a wrecking ball to them a little bit. And so I think, in some ways, maybe it was in anger. Also as sort of how limited our perception of old Hollywood has become. This sort of image of elegance and glamour and our image of the 1920s has become nothing but bobbed haircuts and flapper dresses and Charlestons, and it’s just any era is more complicated than that.

But the ’20s sort of, more so than any other era, it’s like I think we’ve maybe lost some ability to see how tumultuous, how radical, how anarchic, how dangerous, how transgressive, how fraught that era was. People coming out of World War I, coming out of the Spanish flu, coming out of decades of Victorianism. And then you find yourself in a sort of city that’s not even quite a city yet in Los Angeles. And this industry that’s not quite an industry yet. And this art form, movies, that half the world considers high in art form and half the world considers pornography and vulgar and trash. And so you have that kind of atmosphere and people are creating within it.

But again, I would sort of argue that there’s just as much love in that depiction as there is hate. And so I kind of don’t agree with the idea of it being in solely either one or the other.

And with the caveat, it’s not always the smartest thing to try to get in someone’s head like I’m trying. But if I’m you, I’m thinking you make La La Land, and as that award season went on, journalists kind of turned on it. And I know you were aware of that. And then you make First Man, which should have gotten way more attention than it did. In a year Green Book wins Best Picture, First Man doesn’t even get nominated. So if I’m you, I’m like, “You know what? Everyone thinks they have me pegged. Well, they don’t. Here comes Babylon.” That’s what I’m thinking.

I think there’s absolutely … something to that. Yeah. Yeah. For sure. I mean, look, I don’t think it’s so much its specifically in reaction to things you’re talking about. Because just for the simple fact that the movie predates La La Land and First Man. I started working on it back in 2008 or 2009. So it was pretty much fleshed out by the time. Well, by time of La La Land and certainly by the time First Man came around. But the basic idea of, “you think you have me figured out, no, you don’t,” I think that’s actually always like, yeah, that definitely resonates with me, the idea of that.

Because I know you read stuff. You’ve told me in the past you read stuff. The first time I met you was at a Toronto Film Festival event the year Whiplash was out, which was not a Whiplash event. And you came up to me and my coworker when were both at Huffington Post and told us, “I read you guys all the time.” And I was like, “Who is this kid?” And someone told me, “Oh yeah, he directed Whiplash.”

That’s funny. I remember. Since then I tried to limit that, so I read less and less and less for my own sanity. But yeah, I think I’ll always have that sort of case of whether it’s good or bad of being a filmmaker who’s a cinephile. Being a filmmaker who grew up not just watching movies, but learning about movies by reading Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, so on and so forth. And also a filmmaker who learned about films through film history. So always, just kind of thinking of these things as parts of history and cogs in the wheel of history and filmmakers careers and all this sort of stuff.

So it’s tough because when I’m making a movie, on the one level, I want to try to forget all of that and just sort of be in a vacuum and just sort of make the movie and nothing else matters. And its existence in the outer world doesn’t matter, or it’s part of some larger career or whatever doesn’t matter. But I think of who I am, how my mind works, I’m not ever fully able to do that. So that’s why everything I make, it’s informed by movies I’ve seen. The movies that maybe I’ve dreamed of making that never did make. The things I’ve read, things I haven’t read. It all kind of goes into the stew…

Well, that’s why I kept saying that. I know you’re a very thoughtful person. There are some directors I’d be like, well, maybe that’s just an accident. But with you, I don’t think anything is an accident. I think if you’re going to put something out there, it’s going to have a point.

I think, yeah, that’s absolutely for sure. And definitely trying to not just demolish expectations of this time period, but demolish expectations of… Certainly I was very aware, let’s say, of what people were going to expect from the director of La La Land doing a movie about the transition from silent to sound.

Right, exactly…

So yeah, I would totally be lying if I didn’t say that loomed in my mind. Not to distill it to a point or thing to say, but ultimately, that’s for the audience to decide. But for me it was to try to take a bigger bite out of the equation of how I do like that idea of Hollywood as being this sort of equation. And you try to take both sides of it in a way that I didn’t try to do and wasn’t really interested in doing in La La Land, and in a way that a lot of movies about Old Hollywood haven’t really tried to do. And that’s completely fine.

It’s not to slight those movies, but just in this case to try to go, Okay. Can we find a way to pack into one movie and to serve even one frame, and every frame of this movie somehow show the worst thing about Hollywood and the best thing about Hollywood? The best that humanity can achieve in terms of art, in terms of the sublime, in terms of expression, and the worst that we ever see from humans. Can we somehow find a way to not just unite those figuratively, but even physically within the frame? That became kind of this guiding principle for Babylon, which means that in some ways, every frame was equal parts celebration and equal parts condemnation. Equal parts love, equal parts hate.

I’d go 70/30.

All right. Well…

I’ll meet you halfway. 60/40.

Oh, no. As I say, once the movie’s done, it’s the audiences, it’s the interpreters, so whatever you say is right. You know what I mean?

That’s not true. I’m wrong a lot.

But I do believe, that’s one of the beautiful things. It’s part of why also I’m so against the idea of directors going back into their movies 20 years later and whatever. Actually, it’s fine if they do them, but just I’m not interested in doing them. I think it’s like, once you finish the movie, you pass it to the audience, it becomes the audience’s. It truly does. And so at that point, I’m happy to talk about it. But at a certain point, nothing I say should ever supplant what an audience might bring to it because it’s just as legitimate as whatever the intention of the artist might have done.

Well, I hope it came across, I am fascinated by this movie and not just what you’re saying about Hollywood, but I hope you can tell I am really fascinated about what you’re trying to say about yourself. And I think you did a really good job of putting something out there that you’re feeling right now.

But by the way, I’m excited also just to hear that, because in some weird way, that is always the goal, right? It’s just no matter what kind of canvas or time period you’re attacking to try to make it personal, or feel personal, ultimately.

‘Babylon’ opens in theaters on December 23rd. You can contact Mike Ryan directly on Twitter.