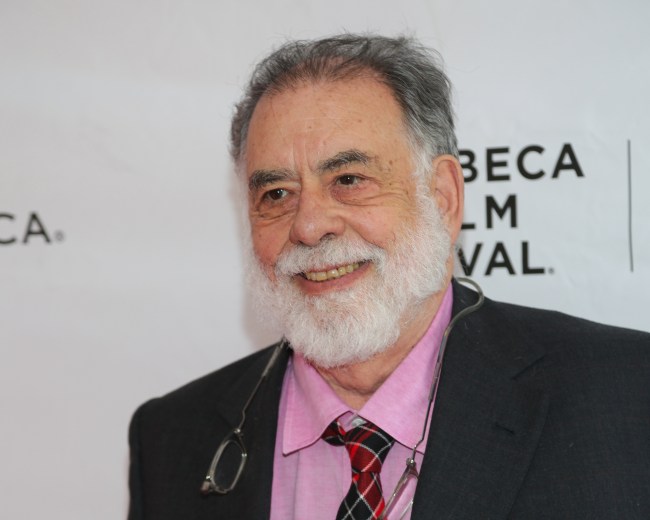

This afternoon, living legend Francis Ford Coppola sat down in Chelsea’s SVA Theatre for a rambling, illuminating conversation with professional sommelier and writer Jay McInerney. They hit the requisite topics, of course — Apocalypse Now, both Godfathers, and a few other entries from his varied filmography passed through the dialogue — but they also touched on the more atypical sort of material that ultimately draws crowds to public back-and-forths such as this. After all, the Tribeca Film Festival wouldn’t have paired the full-bodied Coppola with the dry, playful McInerney if they weren’t going to discuss wine, at least a little.

Below, Uproxx reviews some of the key lessons that Coppola imparted during this uncommon opportunity — savor this article’s notes of persimmon, inviting bouquet, and clean finish.

1. Coppola saw the digital writing on the computerized wall years before the rest of us.

Coppola described himself as a “former boy scientist,” and that interest in technology gave him some valuable perspective on the imminent digitization of film. Coppola recalled a time around 1979, when he speculated that if audio tracks could be isolated and artificially manipulated — “if you could take one saxophone and make it sound like 20 saxophones” — then the same could be done for the image, which was at the time a slave to the careful chemistry through which film strips are prepared for exhibition. He imagined a future where completely computerized programs could replace the exhaustive snipping and cutting of the editing process. “You no longer cut a film,” he said. “You compose a film.”

2. He has accepted that superheroes are king, but he’s not exactly pleased about it.

Coppola was one of the visionaries who rose to prominence during the ’70s and helped spawn a New Hollywood wave of artistically accomplished films that debuted to huge box-office returns. The studio heads were pleased as punch at the young upstarts’ output, and, as McInerney puts it, “gave [them] the keys to the kingdom.” (Coppola corrected him, “Well, we swiped the keys.”)

Times have changed, however. Coppola spoke about the ever-widening divide between massively budgeted studio pictures and small indie projects. He mentioned the superhero genre as the current hot trend in studio filmmaking, and looked back fondly on the days when studio were willing to gamble on original ideas from bold creators. The difficulty many creators have finding funding has seriously frustrated him as well; he confessed to having thrown his Oscars out the window in a rage when he felt like Apocalypse Now would never happen.

3. TV may be the future, but that doesn’t mean he can’t change the landscape.

Coppola has a strange, novel outlook on the future of TV. He seemed a bit resigned as he explained that the differences between TV and film have all but disappeared, but laid out plans for an entirely fresh approach to the medium. Rather than conducting a TV program like a cycle of plays, his chosen comparison, he wants to create what he refers to as “live cinema.” His method sounds insanely ambitious and solidly impractical, but hey, that’s never stopped the director of Apocalypse Now before: the film would be performed, cut and broadcast live, but not quite in real time. He likens it not to the recent live musicals mounted by the major TV networks (he doesn’t like the look of those, either, taking a moment to detail why the zoom-lens requires increased overhead light and results in a “soap opera” look), but of all things, to baseball-game broadcasts. Footage can be captured, delayed for a moment, and edited into the feed live without missing a beat. He mentioned the upcoming TV adaptation of A Few Good Men, noting that the courtroom setting and dialogue-driven nature of the film make it ripe for the format. But that’s not his style: “I want to do Lawrence Of Arabia live.” Famous last words!

4. He still believes in the movies as a holy, personal force.

With a laugh, Coppola copped to yelling at movie theater screens when they display commercials before the feature presentation. He appreciates the sacred nature of the space, and regards movies as a force for personal evolution. “When you’ve been working in a form for long enough,” he said, “you need to kill yourself. You need to be reborn and become a student again.” Seventy-seven years old, arguably the greatest living filmmaker, and he’s still learning.