Once upon a time, way back in the ’90s, some music critic — it’s not clear who exactly, but anecdotal evidence suggests that it was a snarky British scribe — invented the term “dad rock” to describe bands who 1) originated in the classic-rock era or 2) sound like they are influenced by bands from the classic-rock era. As reductive shorthand, dad rock was originally intended as an insult against supposedly backward-looking, musically conservative acts. But over time, dad rock was slowly embraced as a term of endearment, in the way that southerners now refer to themselves as rednecks. Why wouldn’t it be a term of endearment? Dads are nice. Guitars are nice. Therefore, dad rock is extremely nice.

Now, another issue has emerged. While there are plenty of great dad-rock bands currently waving the flag for the Springsteen-loving, salt-and-pepper beard set, rock music is no longer prominent enough in mainstream culture for dad rock to act as an easily recognizable emblem. The boomer dad who loves Steely Dan, or the Gen-X dad who loves Wilco, don’t necessarily share the same tastes as a millennial dad. “Dad rock is typically assumed to be music for straight, white, American dads, despite the observable truth that not all dads are straight, white, or American,” The Outline recently observed. “When we talk about dad rock, we talk about just one kind of dad.”

For instance, plenty of dads who came of age in the ’90s and ’00s love hip-hop, a genre whose history now stretches back about 45 years. While rock is still 20 years older, hip-hop is nevertheless firmly ensconced in middle age, making it ripe for dadness.

And yet “dad rap” doesn’t have quite the same connotation that “dad rock” has. Part of this is a function of how each genre has preserved its own history. For all the deference given to “old school” acts, hip-hop’s essential energy comes from constant reinvention — sounds and styles change quickly, which inevitably causes all but a small handful of artists to fall by the wayside. In rock, however, there’s a thriving legacy industry that keeps older acts on the radio and inside arenas and stadiums for decades after they stopped having hits. As a result, in the common narrative of pop music, rap is still seen as “kid” music whereas rock is “nostalgic,” even though plenty of young people are still forming bands and millions of graying music fans listen to hip-hop as a way to relieve their pasts.

Will a “dad rap” movement analogous to classic rock emerge to keep the hitmakers of yesteryear alive for future generations? This year might mark a turning point. In 2018, the divide between older rappers like Jay-Z, Kanye West, Pusha T, and Nas — all of whom are north of 40 — and the younger generation of Soundcloud rappers that have bum-rushed the pop charts with minimal mainstream exposure has never been starker. This dynamic, between a faded but still famous old guard and upstart youngsters pushing the genre forward, has existed in rock for decades, but it feels new in hip-hop.

To help make sense of these changes, I propose this dad rock-to-dad rap conversion chart. Because the stature now afforded to the Rolling Stones and David Bowie will soon be passed to the hip-hop generation, if it hasn’t been already.

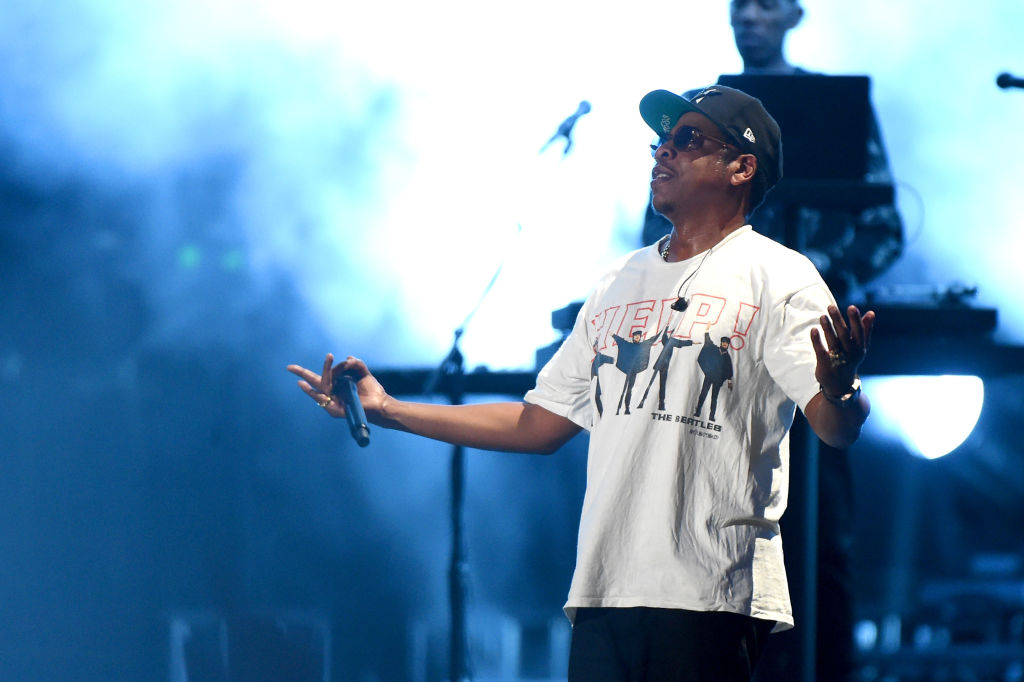

Jay-Z is The Rolling Stones

Both are legends. In their prime, they did it as well as anybody. But currently, they exist as generic symbols for their respective genres. People see the Stones now because they have an important client in town “who likes seeing rock shows” from a nice seat in a luxury box. Just don’t ask them to name a track on Sticky Fingers that isn’t “Brown Sugar” or “Wild Horses.” Jay-Z is like that for hip-hop. Yes, 4:44 was pretty good, but so is Voodoo Lounge. The part of his career in which he was merely okay is now much longer than the part in which he was undeniably great. His Some Girls is The Black Album.

Eminem is the Eagles

Marshall Mathers, like Glenn Frey, is a Detroit native who works out his petty issues with “witchy women” who have “lyin’ eyes” by making absurdly popular, stadium-filling jock jams. Later, when he sought a late-career boost on 2013’s The Marshall Mathers LP 2, he sampled Joe Walsh — a strategy that also worked for the Eagles when they hired Walsh right before making their most popular album, 1977’s Hotel California.

Kanye West is David Bowie

Everybody loves David Bowie now. But in his prime, he was a polarizing polymath and button-pushing contrarian who briefly flirted with fascist iconography in the mid-’70s. The classic album he released in the midst of this controversial era, 1976’s Station To Station, is disjointed and coke-fueled and contains only six tracks, which makes it comparable to this year’s Ye. (To be clear, Station To Station is much, much better than Ye.)

Drake is Tom Petty

Drake is the rare rapper who makes sense in the context of the older Gen-X stars and the Soundcloud kids. (He has beefed with both Pusha T and the late XXXtentacion.) Tom Petty had a similar dynamic as a cross-generational icon, in that he could hang out with musicians 10 years older (including every other dude in the Traveling Wilburys) or 10 years younger (such as famous fans like Dave Grohl and Eddie Vedder). Therefore, Drake is Tom Petty. (Also, in this analogy, Drake’s long-time producer Noah “40” Shebib is Mike Campbell.)

Kendrick Lamar is Bruce Springsteen

Kendrick, like Drake, seems too young to be considered dad rap. Then again, it’s hard to imagine 6ix9ine winning a Pulitzer. As the most revered rapper on the planet, Kendrick courts grown-up prestige, where everything he says and does is freighted with so much meaning. The way people talk about Kendrick Lamar is reminiscent of how Bruce Springsteen was regarded in the mid-’80s, when Born In The USA put him at his commercial and critical zenith. He’s a pop star who is treated like a politician.

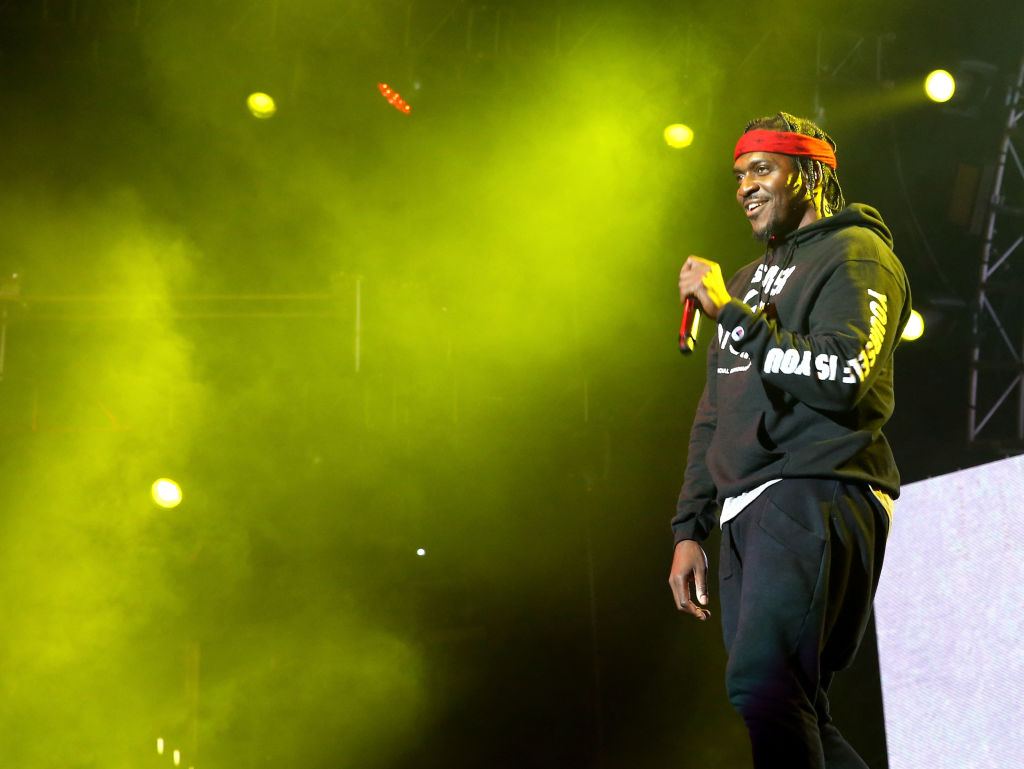

Pusha T is Lou Reed

A cult-level artist revered by his peers who is obsessed with writing about drugs — that bio applies to both of these guys. Lou sang about buying heroin and Pusha T’s specialty is songs about selling cocaine and/or crack. But no matter which side of the equation you’re on, it still requires a lot of waiting for your man.

Nas is Pearl Jam

Hear me out: A classic debut (Illmatic for Nas, Ten for Pearl Jam) that overshadows everything else in the catalogue, though hard-core fans will argue that the second (and possibly sixth) records are actually better. If you were alive in the mid-’90s, you probably overrate this album. If you were born after the mid-’90s, you probably enjoy annoying older people by insisting that this album is boring.

The Roots are Wilco

Both started out as traditionalists and evolved into sonic experimentalists. Both have excellent discographies that are adored by critics and appreciated by (part of) the general public, though they both are probably better live. And while Questlove and Jeff Tweedy like to appear as though they don’t care how their hair looks, I would bet that they actually care very much about looking precisely disheveled.

OutKast is The Beatles

It’s possible to reach a certain saturation level where it seems like so many people believe that you are the best at what you do that it actually becomes a little annoying. OutKast hit that mark around the time of “Hey Ya,” whereas The Beatles hit it around Revolver. Then John Lennon provoked a backlash by comparing his band to Jesus Christ. Later, he left the music business to bake bread and be a father, which is basically what Andre 3000 has done since OutKast broke up.

Beastie Boys are Led Zeppelin

Both were initially reviled critically for making horny, bombastic trash, and then celebrated for creating some of the most sonically pleasurable albums in the history of the genre. What ultimately unites these two is an undying love for John Bonham drum breaks.

A Tribe Called Quest is The Kinks

This is the “we were never the biggest band, but anyone who cares about our genre thinks we’re the best” lane.

Wu-Tang Clan is Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young

Self-explanatory.

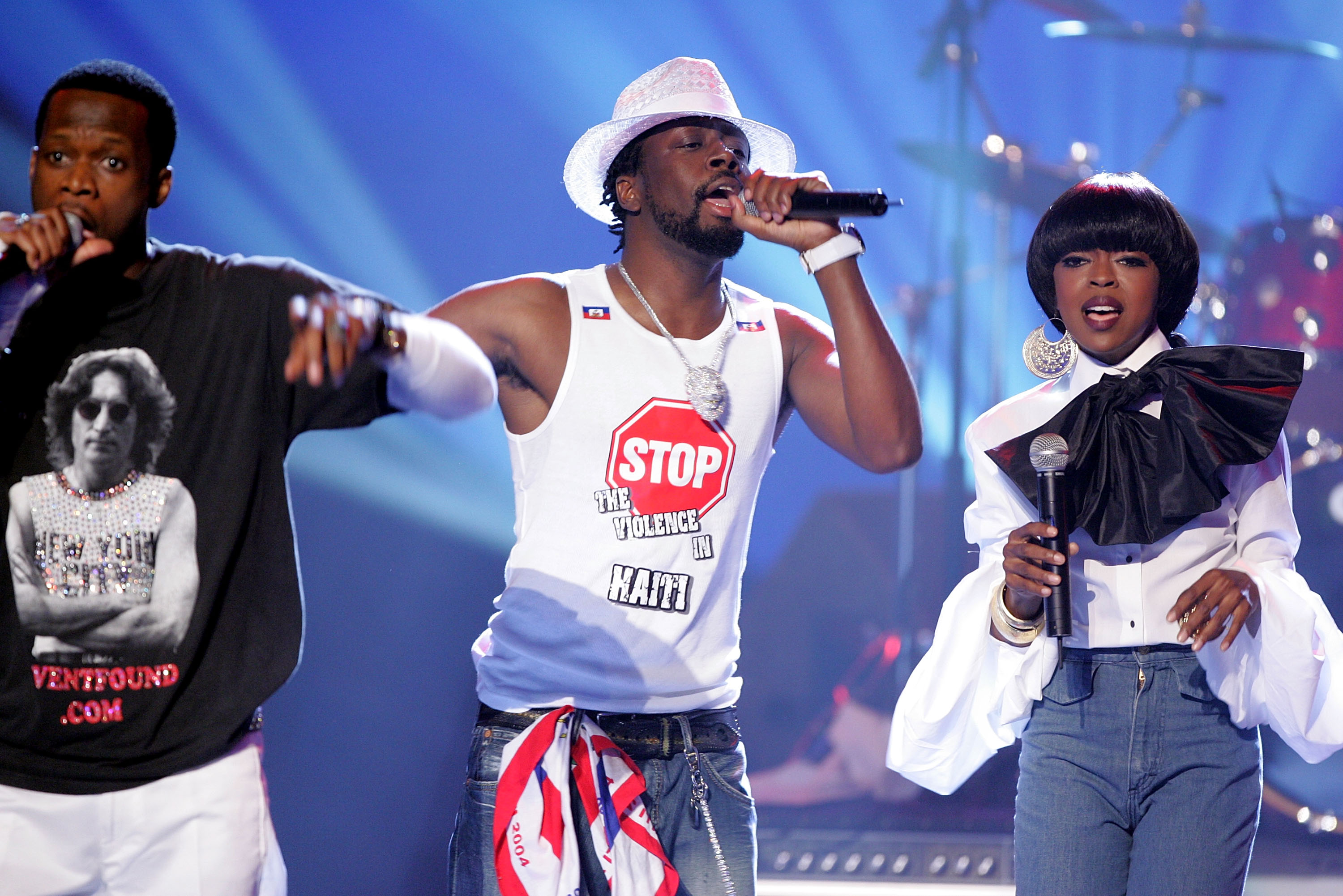

The Fugees are Fleetwood Mac

Self-explanatory.

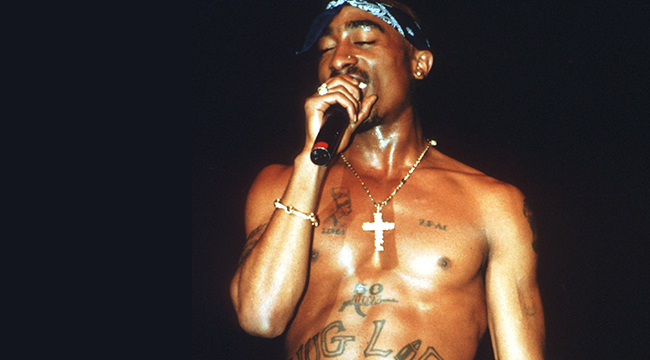

Tupac is Jim Morrison

Nobody wanted to believe that either of these guys were dead after they died, even if it made complete sense that they passed on at a tragically young age. In the afterlife, they inspired cults that romanticized their every thought, word, and deed, making their iconic status seem overbearing at best and slightly ridiculous at worst to subsequent generations. But you can’t take away their respective signature achievements — writing great driving songs about Los Angeles.