Next week, as another installment of South By Southwest kicks off in Austin (assuming it doesn’t get canceled due to global pandemic), I am going to engage in my usual celebrations over not having to attend this year. In my office, I will sit in a comfortable chair while sipping on cold water that doesn’t cost $5 per bottle. I will then walk to the bathroom conveniently situated across the hall and use it without having to wait in line for a half-hour. I will then return to my office and appreciate the lack of omnipresent branding on the walls.

It will be glorious.

There was a time in my career when I looked forward to SXSW. It was a rite of passage for any music journalist, a not-quite-legitimate excuse to spend a week in early spring scamming free drinks and mainlining barbecue and tacos with the ostensible purpose of “discovering” up-and-coming acts. Though the actual journalistic purpose of SXSW already seemed suspect by the time I worked at a publication willing to pay my way to Texas. For one thing, readers didn’t seem terribly interested in reading reviews of shows that no “real” people — i.e. normals not affiliated with the music industry, aka those very same readers — had no chance of ever attending. And then there was the fact that no artist or band actually seemed to get a tangible boost from SXSW anymore. In a world of social media and streaming music and video, where “real” people and journalists have equal access to the buzziest acts from the moment they achieve any semblance of notoriety, going all the way down to Texas to supposedly “cover” this “news event” went from having dubious value to virtually zero worth at all. (Shrinking-to-nonexistent travel budgets for music writers didn’t help matters.)

The last major story related to a largely unknown indie band coming out of SXSW that I remember occurred back in 2010, the first year I attended. Though it was hardly “a star is born”-style coronation. It was, in fact, quite the opposite.

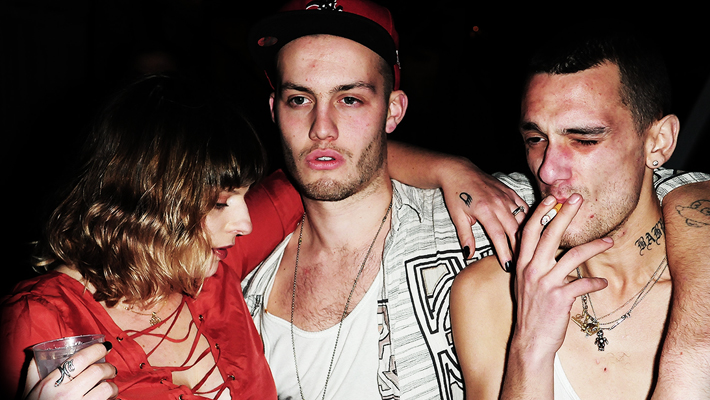

The sullen group of individuals featured in the video above made up a trio from Michigan called Salem. Don’t feel bad if you don’t remember them, or have never heard of them in the first place. In 2010, they released their debut album, King Night, which was followed by an EP in 2011 called I’m Still In The Night. There have been no new Salem releases since then.

But believe me, a decade ago, Salem was kind of a big deal. They were widely considered as the figurehead act of a new microgenre called Witch house, which incorporated elements of goth and shoegaze with electronic music and southern hip-hop. And then there was Salem’s sordid back story, loaded with lurid tales of the members’ dalliances with heroin and cocaine abuse and as well as male prostitution in seedy midwestern gas stations. In this context, there was no doubt that the title of the band’s 2008 EP, Yes, I Smoke Crack, was intended to be taken literally, and the music press fell in line accordingly.

But all of this is just a preamble to that video and this video, which capture Salem’s infamous performance at the Fader Fort and changed the band’s career forever. I understand that I’m using “infamous” a little loosely here — most people don’t remember this or care that it ever happened. It is only infamous for me and people like me who followed SXSW in 2010. I’m talking, at most, about 150 or so people. Nevertheless, this video deserves to be famous, because it is one of the worst and least competent musical performances by a supposedly professional act to happen in the early 21st century.

Let’s briefly break down the performance of “Tent”: The song’s minimalist musical bed is created by a burnout-looking dude playing a Korg, and a burnout-looking woman playing a different keyboard but mostly just evocatively smoking a cigarette. Together they create a weak, unconvincing soundscape for another burnout-looking dude who is rapping very poorly with a highly affected and exaggerated patois that, at best, could be described as awkward. (At worst, it’s a racist caricature.) “Now my dick hard so go down on it, haha!” he says, with a smug smirk that practically screams “Hit me in the face with an anvil!”

You don’t have to be a music critic to immediately recognize what’s annoying, off-putting, or even offensive about this performance. It sounds like garbage. It looks like self-parody. And it feels like wanton half-assery that amounts to unforgivable contempt for the audience. You won’t be surprised to learn that Salem was eventually booed off the stage.

It’s hard to quantify now just how much of a sensation these videos caused in 2010, if you happened to follow indie music. (Especially now that many of the blogs written in the immediate aftermath were posted on websites that no longer exist or have incomplete archives.) But my memory is that Salem’s epic fail at SXSW was a big deal at the time. While Salem was only a cult act associated with a gimmicky musical movement that seemed to lose steam almost immediately after music critics started writing about it, the videos galvanized critics of the era’s larger indie culture. In a small way, the Salem incident helped to shape how music was written about as the decade unfolded, as the media steered away from goth-y, glowering indie groups of Michigan and toward more solidly professional pop stars.

More than anything, it was the lack of any discernible effort on the part of Salem that rankled people the most. Writers who were already skeptical of the aloof, arrogant insouciance that had come to define the much-derided “hipster” stereotype of the era — as well as the insider-ish, fawning media coverage it frequently inspired — now had an extremely obvious Exhibit A for their case against indie exceptionalism. Anyone who felt that obscure, underground acts were garnering too much mainstream coverage — supposedly at the expense of enormously successful pop singers, who actually deserved the attention — could point to Salem as the perfect example of typical trucker-hat trash elevated to the highest echelons of fame and prestige against all reason or logic.

“Salem are living proof that hipsters will buy into anything if you tell them it’s cool enough: They’re like The Brown Bunny of bands,” critic Allison Stewart scoffed in The Washington Post. The newspaper had assembled a panel of writers to weigh in on Salem under the headline, “Are Salem Really The Stupidest Band on Earth?” (For the record, I think the Vincent Gallo movie that Stewart referenced is pretty good!) Unsurprisingly, the writers seemed to agree that, yes, Salem really were the stupidest. “We are supposed to be impressed by them slowing down a stupid Britney Spears song and making a video with night-vision strippers and soldiers?” another writer asked. “I am not.”

The Village Voice was even more brutal. “The infamous videos of them performing at the Fader Fort include the band doing what they do best,” reads a scathing end-of-the-year blurb published nine months after SXSW, which proceeds to slam Salem for their listless stage presence as well as allegedly engaging in “an atonal, arrhythmic Southern-rap minstrel show,” before concluding that “they are the living, breathing American Apparel-clad definition of white privilege.”

These sorts of write-ups were directed at Salem in relation to King Night‘s release that September, though they seemed to be just as much about the SXSW appearance as the album. Salem was the rare group that created an indelible media narrative in the wake of the Austin festival; unfortunately, it was precisely the kind of narrative that all artists dread. I reviewed King Night for the A.V. Club, and I was as unsparing as anyone: “An aggressively regressive stew of cheap horror-movie atmospherics, booger-flinging beats, rudimentary rapping, and occasional (perhaps accidental) moments of genuine profundity, Salem’s King Night is an Insane Clown Posse record that thinks it’s too clever to be an Insane Clown Posse record.”

You can imagine my surprise when I revisited King Night this week and found that I liked the album way more than I expected. Not only did it not seem like transgressive trash, it sounded … normal. Lately, I’ve been entranced by Miss Anthropocene, the dance-goth semi-classic made by 2020’s resident anti-hero and music-critic disruptor, Grimes, and found that King Night slotted more than comfortably next to it. After Yeezus, Spring Breakers, Lil Peep, and 100 gecs, the album’s palette of sinister, vibe-y, internet-native, and genre-bending music is practically pop.

While it wasn’t necessarily wrong to accuse these people of being stupid, it does seem like a separate question from whether the music was actually good. The biggest strike against King Night remains its muddled relationship with hip-hop, which is irreverent to the point of occasionally feeling like (perhaps) an unintended insult. Ultimately, however, I tend to agree with the nut graph of Larry Fitzmaurice’s Pitchfork review, which has aged the best of all King Night takes I’ve seen: “When you actually listen to King Night, it’s easy to be amazed that these dickheads made a record so interesting and sonically detailed.”

However, in the wake of the SXSW controversy, there was less focus on what “these d*ckheads” were capable of producing than on their utter failure to look competent on stage. Though in that respect, Salem might have just been ahead of their time. “If we do anything, we wanna do it exactly to our aesthetic and make it a really comprehensive experience,” said one of the group’s members, Heather Marlatt, at the time, “and not just getting up on a stage and playing an instrument and going away.”

That doesn’t seem all that far removed from how a lot of young musicians who break big online now approach their careers. The idea that a new act must “prove” themselves in live performance for industry professionals at a festival that has at times exploited their labor seems a little antiquated at the dawn of this decade. So what if Salem sucked live? Do you know how many popular acts suck live these days? There are other ways to make it. In the end, Salem died on stage so others could live.