If I were to ask you to name a rock and roll historical landmark, chances are that you would have absolutely no problem answering that question. After all, there are plenty to choose from. You could go with the street crossing in front of London’s Abbey Road studios, made famous by the cover of The Beatles’ 1969 record, Abbey Road. Or you could go stateside and roll with Graceland, the compound in Memphis, Tennessee that Elvis Presley built with the money made ripping off black artists; or the dairy farm in upstate New York that held the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in 1969, a music festival that defined a generation thanks to performances by the likes of Jimi Hendrix, The Grateful Dead, and The Band.

But if I were to ask you to do the same for hip hop, would you be able to?

That was a rhetorical question. For whatever reason — cough, racism — we don’t give the same geographical consideration to rap as we do to other genres (country has the Grand Ole Opry; Tejano has the Day’s Inn motel room in Corpus Christi, Texas, where Selena was fatally shot). It’s kind of bonkers if you think about it. Not only has hip hop dominated our culture for the last three decades, but its subgenres, which are very much shaped by their geography, lend themselves to this type of commemoration.

So, in an effort to right this wrong, I’d like to submit one specific hip hop landmark for your consideration: The Compton swap meet in Compton, California.

Officially known as the Compton Fashion Center, the swap meet was a former Sears store that was converted into an indoor flea market by a Korean immigrant in 1983. It was a public space where hundreds of vendors — mostly people of color — made a living selling an assortment of goods until its closure in 2015. But the swap meet was more than that. It was also a hotbed for west coast rap, one with ties to three artists that defined the genre for their respective eras: NWA, Tupac, and Kendrick Lamar. In the spirit of honoring this landmark as it properly deserves, here’s a breakdown of why exactly the Compton Fashion Center is so important, its connection to the aforementioned artists, and why its loss should be, and is, deeply felt.

“Straight Outta Compton”

According to the 2015 biopic Straight Outta Compton, NWA formed because Dr. Dre, then a broke AF DJ with World Class Wreckin’ Cru, approached Eazy-E, a local drug dealer looking to go clean so as to avoid being murdered or imprisoned, at a club and begged him to start a record label. That conversation really did happen, but it took place over the phone and it was orchestrated by Steve Yano, the proprietor of a record shop at the Roadium Swap Meet, in Torrance, California, that was converted into an open air flea market/bazaar. Yano, a former school teacher, specialized in selling the hottest hip-hop and underground records.

“He has stuff nobody else has, stuff nobody else has ever heard of,” music journalist Terry McDermott wrote of the record store owner in his 2002 Los Angeles Times Magazine cover story on the history of NWA’s early beginnings. “He has stuff so new it doesn’t even exist yet (not officially), stuff with no labels, no packaging, just the stamp of the new.”

Yano was a big deal in the pre-NWA era of west coast rap mostly because he was one of the only people actually selling rap records in southern California at the time. Before they were sold at your local record shop, the first gangsta rap albums — and its predecessors, like Dr. Dre’s hour long mixtapes (embedded below for your listening pleasure) — could only be found at swap meets in south central Los Angeles. McDermott credits this to mom and pop shops filling a void left by the vertical integration of the music industry, which only made and promoted well-tested music they knew would make them money.

“Low profit margins made store rack space too valuable to waste on unknown artists,” he explained of the big chains.

Enterprising vendors with money on their mind sold what more mainstream retailers wouldn’t touch. One such peddler was Wan Joo Kim, a North Korean immigrant who opened Cycadelic Records at the Compton Fashion Center in 1985. Kim didn’t know or care much about rap, but he ended up selling it anyway on the recommendation of a local wholesaler. It was a wise business decision that unwittingly made Kim one of the first distributors of a burgeoning musical subgenre that would quickly take over the world. You know that montage in Straight Outta Compton where they’re pressing copies of “Boyz In The Hood” en masse and Eazy-E is just moving boxes of the single to his car? He was taking them to places like Cycadelic Records. According to a 2012 Los Angeles Times profile of Kim, the rap merchant and his family developed such a rapport with Eazy-E, that his wife would lovingly yell at the rapper to pull up his pants whenever he would come by to drop off a shipment. You couldn’t get NWA’s first 12-inch singles anywhere else, so eager would-be listeners flocked to Kim with their cash in hand and regularly bought him out.

It didn’t matter that the music was deemed too explicit for radio play. People like Yano and Kim, driven by the the “cash rules everything around me ” mentality emblematic of the hip hop ethos, created spaces where rap could incubate. Places like Cycadelic Records sustained an underground movement long enough for it to break through into the mainstream. And break through it did. Pretty soon, the big labels went all in on gangsta rap — once they realized white kids in middle America were listening to it — and that they could make serious bank off of it. But none of this wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for the swap meets.

“[These stores] helped make hip-hop possible in the first place,” McDermott posited.

“You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge”

The birth of west coast rap coincided more or less with the rise of Yo! MTV Raps. The hour long show, which featured rap music videos and artist interviews, was a surprise hit for the youth-centric network when it premiered in August 1988 and would prove to be a major driver in the globalization of hip hop culture. (Side note: That MTV went all in on the show can and should be seen as an admission that they were on the wrong side of history by excluding black artists from their airwaves — David Bowie famously called them out on this in 1983.)

More importantly though, Yo! MTV Raps brought hip hop to anyone with a cable subscription nationwide. “That’s how we sold two million,” Bryan Turner, owner of NWA’s label, Priority Records, said of Straight Outta Compton in Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, arguably the best book about hip hop history ever written.

“The white kids in the [San Fernando] Valley picked it up and they decided they wanted to live vicariously through this music,” he added. “Kids were just waiting for it.”

All of sudden, Eazy E & Co. had a platform where they could tell everybody what the f*ck they had to say. In short, their message was that west coast was the best coast.

“NWA dropped hip-hop like a ’64 Chevy right down to street-corner level,” Chang wrote in his book, adding that the group “Lowered it from the mountaintop view of Public Enemy’s recombinant nationalism and Rakim’s streetwise spiritualism, and made hip-hop narrative specific, more coded in local symbol and slang than ever before.”

“After Straight Outta Compton, it really was all about where you from,” he surmised.

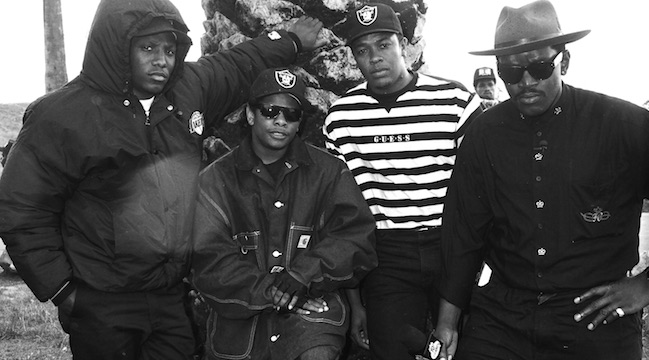

This “regional chauvinism” — a term coined by McDermott — was on full display when NWA finally appeared on Yo! MTV Raps on April 8, 1989. MTV had previously banned the group’s first music video, “Straight Outta Compton,” because it was deemed too offensive (yet another example of the network being on the wrong side of history), but eventually relented because you couldn’t legitimately have a show about rap and not feature its biggest group. In the episode, NWA take host Fab Five Freddy on a tour of their turf, and one of their stops was none other than the Compton Fashion Center.

“The Compton swap meet is something like a flea market, you know,” Eazy E explained to those watching who might not know, “We come here and get the Locs, and shirts, and Levis, the whole hookup, yeah, you know it.”

It was also, according to an awkward as hell Dr. Dre, the best place to pick up females.

At first glance, this clip might seem inconsequential outside of NWA’s first MTV appearance. After all, it’s just some kids talking about where they hang out. But that’s precisely why it’s so important. NWA presented the Compton Fashion Center as a stand-in for their version of youth culture. It’s no different than the opening montage of Amy Heckerling’s 1982 film, Fast Times At Ridgemont High.

To Live And Die In Tupac’s LA

You can’t legitimately make the case for something representing west coast hip hop without it having some kind of connection to Tupac Shakur. Pac is west coast hip hop. He took the idea of rap song as a documentary of hood life to the next level with tracks like “Changes” and “Keep Ya Head Up.” He was the most vocal trash talker in the west versus east coast feud that dominated hip hop for much of the ’90s (“Hit Em Up,” a takedown of his east coast counterpart, The Notorious B.I.G., remains the greatest diss song ever recorded). Pac was the biggest regional chauvinist that ever lived, as evidenced by the fact that he made the two greatest west coast anthems of all time. It is in these two songs where we find our Compton swap meet connection.

The first jam in question is “California Love.” The 1996 song is so iconic and bombastic that Death Row Records, Tupac’s label, made two music videos for it. You’re no doubt familiar with the Hype Williams version, which has Pac and Dr. Dre (he made the beat and rapped the first verse) walking around a dystopian world inspired by Mad Max: Beyond The Thunderdome. The second video (embedded below) is less famous but equally as important. (Side note: The second video is for the remix version of “California Love,” which is, musically speaking, better than the original because it’s funkier and features more of Roger Troutman’s voice box.)

At first glance, the Compton Fashion Center sequence seems pretty straight forward: Pac is going to Dre’s party and he needs new clothes, so he goes to the swap meet in search of an outfit. But why would Tupac, who at the time was living in a mansion in Woodland Hills, California, drive upwards of 60 miles to and from Compton? And why would he go to a swap meet, a place where name brand threads are guaranteed to be counterfeit? Also, Tupac was rubbing shoulders with some of the biggest names in fashion. Why not just hit them up at their storefronts in Beverly Hills, a much shorter drive than Compton?

Tupac was very much concerned with being authentic. He didn’t get “Thug Life” tattooed across his stomach because it looked cool (which it does, by the way). He did it because he was very much about that life. He talked about the Truth in just about every interview he gave.

My best guess for why part of the video is set at the Compton Fashion Center is that he wanted to show what a real gangsta, one without his riches, would actually do in that situation. The swap meet then becomes a physical representation for the hood life Tupac raps about. This theory still holds when you also factor in the music video for “To Live & Die In L.A.,” the second of the two west coast anthems he’s responsible for.

“To Live & Die In L.A.” is more reflective than “California Love.” Very few works of art, regardless of genre or medium, do a better job at capturing LA’s essence than this 1996 track. In four minutes and 32 seconds, Tupac describes the places (“It’s the city of angels and constant danger / South Central LA can’t get no stranger”) and people (“It wouldn’t be LA without Mexicans / Black Love, Brown Pride, and the sets again”) that define the city. The music video for the song accomplishes the same thing. It is a visual tour of black and brown staples across Los Angeles, taking the viewers to places like the Estrada Courts murals, the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza shopping mall, Lueders Park, and, of course, the Fashion Compton Center.

King Kendrick

The most recent and perhaps most compelling argument for why the Compton Fashion Center should be thought of as a holy place of hip hop was made by none other than Kendrick Lamar, the undisputed greatest rapper alive.

Compton has always played a crucial part in Lamar’s narrative. It informed and shaped the way he sees the world, and despite his massive success, he has never ventured far from it creatively (and literally, if you take the claim he made in “The Heart Part Four” — “I’ve got a condo in Compton, I’m still in reach” — at face value). In DAMN., the city is a character unto itself, one that exemplifies the precariousness of life. It’s Anton Chigurh flipping a coin, deciding whether you live (“Duckworth”) or die (“Blood.”) It is a lifelong tormentor that you have to watch your back from, one that never lets you feel comfortable regardless of how alright everything seems to be (“Fear.”) And at the heart of Kendrick’s Compton is the swap meet. He made this apparent on April 1, 2015, with the release of the “King Kunta” music video.

The Director X-helmed music video follows Kendrick Lamar around his hometown, spitting bars about how he is the greatest rapper alive and how his contemporaries are nowhere near his level — a recurring theme for him as evidenced by more recent tracks like “Humble,” and 2013’s “Control,” which started as a Big Sean song but became Kendrick’s after the latter’s savage declaration of war against pretty much everyone, including Big Sean himself. It’s an ode to the city that made him, and it re-establishes Compton as the epicenter of hip-hop. Because Kendrick Lamar is the king of hip-hop, he gets to pick from where he oversees his domain. He is explicit with his choice. A good part of the video shows King Kendrick squatting over a throne located in the middle of the driveway of a Compton home.

But “King Kunta” the music video is more than just another example of geographical chauvinism. It’s also Kendrick Lamar boldly claiming to be the rightful heir to Tupac. K-Dot has said on multiple occasions that he decided to become a rapper when he was eight-years-old, after his dad took him to see Tupac and Dr. Dre film part of the “California Love” video (again, not the Thunderdome version) at the swap meet. He recounted a version of this very formative event in a 2015 Rolling Stone cover story, later reiterating just how fateful this event was in a tribute published on Tupac’s website on the 19th anniversary of his death.

“The people that you touched on that small intersection changed lives forever,” Lamar wrote, very much counting himself among those blessed by Pac. “I told myself I wanted to be a voice for man one day. Whoever knew I was speaking out loud for [you] to listen.”

A young Kendrick would even rap about this blessed encounter in “Compton State Of Mind,” a song from a pre-fame mixtape that uses the music from Jay Z’s “Empire State Of Mind.”

You would think then that Kendrick Lamar’s decision to shoot at the Compton Fashion Center, the very same place where he found his calling as a child, was a conscious one, right? Nope.

“I’d heard [the story about a young Kendrick seeing ‘Pac at the swap meet], but I don’t know anything definitely,” Director X explained to Complex in breakdown of the music video days after its release. “We went there really just to keep with the West vibe. I mean we knew that Wal-Mart bought it, but once we got there and saw it’s actually closed it became this kind of big going away party.”

They shot at the Compton Fashion Center because it’s a local landmark. Not filming there would be like you going on vacation to Paris and not taking pictures at the Eiffel Tower. It wasn’t until Kendrick Lamar was actually on top of the roof performing for his home crowd that the Tupac connection became clear.

“[All] them kids was out looking and a good friend of mine said, ‘You was one of them kids looking at ‘Pac when he was up here doing that; now they’re looking at you’,” the rapper told MTV’s Rob Markman in 2015. “It blew me away, tripped me out that fifteen years later I’m doing that same thing ‘Pac was doing right in Compton.” (Side note: it was actually more than fifteen years later since the “California Love” video was shot in 1996 and “King Kunta” was filmed in 2015, but you get the point.)

It was at that point that it dawned on Kendrick Lamar that he was his generation’s Tupac. If hip-hop were The Lion King — bear with me here — this event would be the scene where Simba stands on Pride Rock, roaring triumphantly after defeating Scar and reclaiming his birthright. Tupac is obviously Mufasa in this analogy, given that they were both murdered and all.

The Hip-hop CBGB’s?

As the title to this chapter suggests, I couldn’t help but to draw parallels between the Compton Fashion Center and the historic New York City rock club. Both places served as petri dishes that spawned important musical movements (in the case of CBGB, the New York underground and punk scenes). Both also have strong associations to culturally significant acts (bands/artists with CBGB ties: Blondie, Patti Smith, Television, The Ramones, Talking Heads). And finally, both locales were shuttered down and converted into retail space. A John Varvatos store now operates where CBGB used to be; a Walmart supercenter recently opened at the former swap meet.

The only real difference is that you can still buy a shirt with the venue’s logo emblazoned on it online, or you could see one of its three awnings at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. The same thing can’t be said about the Compton Fashion Center. But maybe one day, the spot will get its rightful commemoration.