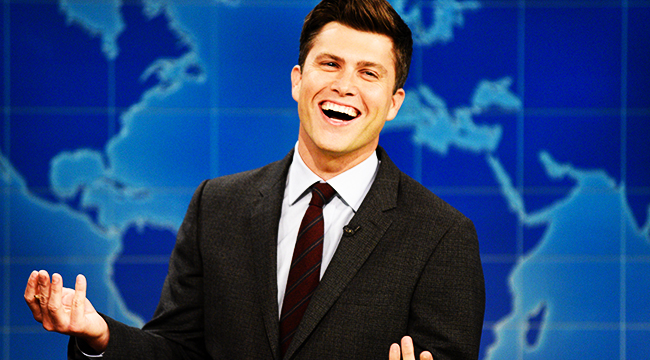

In 2015, Rolling Stone ranked every cast member of Saturday Night Live from worst (Robert Downey Jr.?) to best (John Belushi!). As is the case with all articles of this sort, the SNL list was designed to generate debate. (As a viewer who came to the show in the late ’80s, Phil Hartman was and always will be the GOAT in my eyes.) However, if a similar list were made today, I suspect there would be more consensus about who belongs near the bottom of the list. I refer to the most despised cast member that I can recall from more than 30 years of following SNL, Mr. Colin Jost.

There have been other SNL cast members that have antagonized a large segment of viewers — your Jim Breuers, your Jay Mohrs, your Victoria Jacksons. But nobody has been quite as disliked, while also being as central to the show, as Jost. Among the people I know who like SNL, Jost (at best) is a benign presence whose essential blandness precludes feeling one way or the other about his tenure on “Weekend Update,” or (at worst) a smug hack who relies far too often on easy, frat-dude punchlines about porno movies and penis sizes.

As for the people who already despise the show — seemingly everyone in my Twitter feed — Jost is nothing less than the epitome of white-male mediocrity, an empty vessel who is handsome (but not that handsome), smart enough (but not all that smart), and, well, passably funny (though only if you grade on a generous curve). He seems less like a comedian than a cardboard ’80s movie villain — like James Spader if he looked like a beefier Andrew McCarthy — with zero self-consciousness when it comes to bragging about how he gets his boat shoes wet at the finest beaches in the Hamptons.

Personally, I’m somewhere in the middle. I don’t hate Jost, though he does reflexively bug me for reasons I hadn’t bothered to contemplate (until now). But I don’t know a single person who is a self-described Colin Jost fan. This might say more about the class of people I associate with than it says about Jost. Because Jost apparently is adored by some extremely powerful people, including Tina Fey (one of the people who hired Jost at age 22 right after he graduated from Harvard), Lorne Michaels (his greatest patron), and Scarlett Johansson (his movie-star girlfriend). Then there are the people who run the Emmys, the editors at the New Yorker, the studio that bankrolled his 2015 semi-autobiographical Adventureland rip-off Staten Island Summer, and the gatekeepers at Netflix who ensure that you can watch this, yes, thoroughly mediocre movie right now.

I think this is what ultimately is so maddening about Jost — that this guy somehow became the prince of America’s reigning comedy institution while also sleeping with one of the Avengers. For those of us who don’t get Colin Jost, however, it’s worth figuring out what they’re seeing that we’re not.

Saturday Night Live to me has always been more like a baseball team than a normal TV show. When I started watching SNL, I became a fan of the franchise as much as any individual cast member. Over the years, I’ve stuck with SNL through good seasons and bad seasons and absolutely atrocious seasons, in the same way that, say, Cubs fans have stuck with their team for decades. If you’re committed to the idea of a team, it will transcend specific lineups and the day-in, day-out vagaries that any club encounters. You keep on caring because keeping on caring is simply what you do.

To carry over this analogy, Jost is a homegrown prospect, joining SNL in 2005 after serving as president of the Harvard Lampoon in college. His entire professional life has been spent at the show — first as a staff writer, then as head writer, and then as a co-anchor of “Weekend Update.” When Jost was promoted to “Update” in 2014, he was viewed as a younger, less-seasoned version of his predecessor, Seth Meyers, who resembles Jost on paper (good-looking, smart, level-headed), though Meyers has an essential empathy for the underdog that Jost rarely seems to display.

From the beginning, a vocal segment of SNL viewers didn’t like Jost, whose lack of on-camera experience resulted in some understandably bumpy moments. Jost’s partner at that time was Cecily Strong, for years one of SNL‘s most reliable cast members. She was also a little awkward on “Weekend Update,” but nonetheless was far more assured than Jost. However, by the following season, Strong was out and Jost was allowed another full season to acclimate to the “Update” desk, this time with fellow SNL writer Michael Che.

And the rest, I suppose, is history. After a period of post-Meyers instability, “Weekend Update” once again is entrenched as SNL’s anchor. And by anchor, I mean that you can sometimes feel SNL being pulled down the bloat of its weekly recurring sketch. (A recent episode hosted by Halsey featured an “Update” that ran about 18 minutes, close to a quarter of the entire show’s running time.)

Viewed from the perspective of a sports franchise, SNL’s 2018-19 season is neither a playoff campaign nor a cellar-dwelling disaster. The episodes have been competent but almost never memorable, the very essence of a ho-hum .500 season. And, as the piece at the center, “Weekend Update” has been responsible for setting that utterly average tone.

The irony of Jost’s polarizing reputation is that he isn’t really a provocateur. (This is also true of the slightly edgier Che, though he’s generally funnier.) Jost never gets in trouble for taking a dangerous position on an important issue — his comedy comes from a place of centrist, dispassionate pragmatism. In that respect, the Trump era has been both a boon (in that it’s focused the public on politics) and a curse (because centrists are now magnets for criticism) for Jost.

In November, Jost garnered criticism on social media for a bit about Amazon’s proposed New York City headquarters that made light of concerns about gentrification. Since many of those worries were expressed on social media, it’s not a surprise that Jost was compelled to throw water on the conversation. Jost’s signature comic posture is to address a furious political or cultural debate as a “reasonable” outsider who is above getting riled up about anything. That was also Jost’s tack in 2016, when he joked that Tinder offering multiple gender identity options was to blame for Democrats losing the presidential election. In both instances, Jost could afford to be aloof because neither Amazon driving middle-class New Yorkers out of their homes nor the recognition of non-binary people affected him personally.

For the most part, however, the extremely “mid” nature of Jost’s comedy has steered “Weekend Update” into safe, predictable waters, which is in line with his “company man” pedigree. While this comparison isn’t entirely fair, I sometimes think back to the mid-’90s, when another white dude that many people despised, Norm Macdonald, hosted “Update.” (Rolling Stone put Macdonald at no. 139 out of 145 on its SNL list.) Macdonald was a provocateur, openly antagonizing the head of NBC by making one O.J. Simpson joke after another. (Then-NBC head Don Ohlmeyer was a friend of Simpson.) When you revisit “Update” installments from that era, it’s clear that the audience also felt confronted … and not very entertained. The silence in Studio 8H is almost terrifying, and yet Macdonald also seemed to lean into that distaste. I imagine it was like watching the Sex Pistols play clubs in the deep south during their only American tour in the late ’70s. If Macdonald was going to be hated, at least he had the guts to make it count.

I don’t know how much Colin Jost pays attention to what people say about him. (Again, he’s wealthy and he’s Black Widow’s boyfriend — Jost is doing great.) But I think the qualities that make him appealing for his SNL co-workers — that homegrown, aggressively norm-core sturdiness — also undermine him with the general public. I’d like to see him embrace being the heel, as he did recently at WrestleMania 35. Being more hateable would actually make him more likable. For now, he’s kind of dull without the conviction of owning his jerkiness.