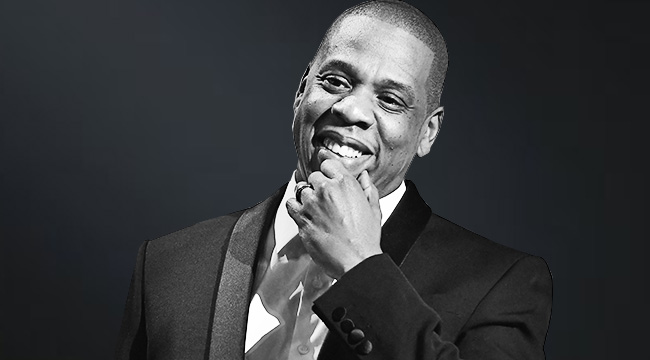

There was a time when, if you asked me who my favorite rapper was, I’d say unequivocally that it was Shawn “Jay Z” Carter — the mid-nineties to be exact (bring on the old man jokes). He was the first rapper whose bars I memorized line-for-line, that would’ve been his verses on Changing Faces’ “All Of My Days” from the Space Jam soundtrack. How could you not love: “Keep the ice out the club lights — change face / Get ‘I love wifey’ on the license plates / Wait — make me think about you even when you’re not around / Use the bathroom, put the toilet seat back down?”

He seemed out of reach, yet down to earth; he wasn’t super rugged and thuggish, like Tupac and his eventual spin-offs Ja Rule and DMX, but he also wasn’t a heartthrob, lip-licking muscleman like LL Cool J. Even at his flashiest, he wasn’t a shiny-suit wearing, Gucci-down-to-the-socks, elaborately-styled like those in Bad Boy’s stable. (Even when he tried to be, he could never really pull it off — see: the infamous “Sunshine” music video.) And he definitely wasn’t a costumed hippie like Native Tongues, who I best related to in content, if not in character. Jay was just a regular guy with money and a little charisma. He looked like someone I’d see walking down the street on my block, in his baggy jeans, fresh sneakers and throwback jersey. Everything was understated, but that flow. My goodness, that flow. Jigga would twist and contort and juggle vowels like the ridiculous nunchuck-spinning scene in the first Ninja Turtles movie, and as a word nerd, I loved every multi-syllabic second.

Then I got older, and Jay got older, and he apparently got bored with rapping, and as he got more bored with rap, I got more bored with hearing him rap. Nowadays, a Jay Z feature on a popular rapper’s newest single — once a cause for immediate headphone-hunting and rewind-button-finger spraining — barely elicits a grunt and a shrug from even the most avid rap fan. And while he’s delivered more than few decent quotables on recent appearances, on the whole, a Jay verse in 2017 is about as humdrum an occurrence as one can imagine in the increasingly colorful world of hip-hop.

What the hell happened?

Well, for one thing, Jay Z got married. That’s a thing that will shift a man’s priorities in a hurry. However, if that wasn’t enough to settle him down — if you believe Lemonade is based on a true story anyway — now he’s a father, and as pretty much anyone with kids will tell you, having kids will upend everything you think is important. For Jay, being the best rapper alive just isn’t all that important anymore. And as a listener, I wonder if I’d be disappointed if it were — after all, I’ve got my own responsibilities, bills, and relationship drama to sort through. Jay, for all his art talk, and fashion-forward name-dropping, still strikes me as just a regular guy.

Which is why it makes perfect sense that he’d pull all his albums from Spotify in favor of Tidal (and Apple Music, for what it’s worth). Spotify pays less per stream than any streaming service other than Youtube, and as the saying goes, “if it doesn’t make dollars, it doesn’t make sense.” Jay owns part of Tidal, an album that seeks to free artists from the constrains of labels and other music industry machination, so why leave his albums available on a rival service that pulls potential subscribers away from his own, only for him to receive a pittance on the royalties in comparison to the splits being paid by — again — his very own service?

After all, this is tantamount to taking food out of his own kid’s mouth, and while no one would argue that Blue and the as-yet unborn twins are in any danger of starving just yet, why would an MC who famously declared, “I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man,” leave money on the table when it’s there for the taking? I know I wouldn’t work for free, and the stakes are a lot lower where I am than in the boardrooms where multi-million dollar deals are made and broken. While this is a move sure to frustrate many listeners, it’s a wiser decision from a business standpoint, like most of Jay Z’s moves since he stopped caring about rap. It behooves Hov to bring more subscribers to Tidal, making more money on the investment side, while getting a bigger piece of the pie per play. That’s how you become a legend in two games, word to Pee Wee Kirkland.

Jay announced a long time ago what his own end goals were with this music thing. “I can’t help the poor if I’m one of them / So I got rich and gave back, to me that’s the win-win.” It’s fitting that one of the mogul’s most endlessly quotable bars describes almost to a T what he’s been working on for the past ten years outside of music. While Jay would be the first to warn listeners to “believe none of what you hear — even if it’s spat by me,” the rapper/businessman/former-criminal born Shawn Corey Carter possesses a list of charitable donations longer than his actual rap sheet — no pun intended. Jay Z has supported charities like: Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, Global Poverty Project, Red Cross, and Robin Hood since the mid-2000s.

In doing so, Jay has become a bridge between the disenfranchised Black folks who come from similar origins as himself and the ivory towers of what we’d consider “success” in America. Once a drug dealer in Brooklyn’s Marcy Projects, then a moderately successful rapper with hits like “Big Pimpin’,” (released 17 years ago today, and where we wasn’t even the star attraction, that distinction belong to the magnificent, late Pimp C), and “Hard Knock Life,” Jay has committed himself to not just rapping about the ‘hood, but actively stepping in and taking action to improve the conditions there. He even penned an op-ed for the prestigious The New York Times last year, using the Gray Lady’s platform to announce that “The War On Drugs Is An Epic Fail.” (Shouts to the incredible Molly Crabapple for illustrating and Dream Hampton for facilitating.)

His latest works focus on shining a light on the criminal justice system — namely, how it discriminates against and regularly fails young men of color in America, especially young Black men. In 2017, Jay partnered with producer Harvey Weinstein to bankroll production of an 8-episode docuseries for Spike TV called Time: The Kalief Browder Story with director Jenner Furst, chronicling the three-year incarceration, civil suit against the city of New York, and eventual suicide of Bronx teen Kalief Browder after a wrongful arrest at the age of 16 years old. The first run broadcast became a number one trending topic on Twitter, eventually reaching over 40 million viewers including streaming and live cable views.

Following up on the success of The Kalief Browder Story, Jay and Weinstein are once again teaming up to produce another eight-part television event for Spike — renaming in 2018 to Paramount Network — entitled Rest In Power: The Trayvon Martin Story, based on the life and legacy of Trayvon Martin. Martin was a 17-year old high school student shot and killed by a neighborhood watch member George Zimmerman, in the Florida community where they both lived. Zimmerman was acquitted on a second-degree murder charge after claiming he shot Martin in self-defense, sparking protests and outrage worldwide.

Only a rapper with the business acumen of Jay Z could become a businessman with the cultural cachet of Shawn Carter; both of these halves are needed to complete the bridge between two worlds that never coincide in the real world. The disconnect between the boardroom and the block shows up in everything from how products are marketed to people of color, to just what products get made in the first place. Someone has to be the bridge, so who better than a regular guy from Brooklyn who just happens to have some money and charm?

Jay doesn’t have to worry about being “bigger” anymore; he’s already the biggest name in hip-hop. Nor does he really have to prove himself the “best” rapper; that legacy is sealed, it’s time for him to move on to something greater. Greater doesn’t necessarily mean leaving behind the environment that he comes from, it means exerting his influence to change that environment so more Jay Zs can flourish, so fewer Shawn Carters get caught up in a cycle of violence and crime, so more Black teens from the block can find their way to the boardroom, instead of ending up like Kalief and Trayvon. Jay may not be the best MC anymore, but he doesn’t need to be to wear the title Greatest Of All Time. His rhymes may have changed the game, but his real goal is to change the world.

Aaron Williams is an average guy from Compton. He’s a writer and editor for The Drew League and co-host of the Compton Beach podcast. Follow him here.