“Between the fear that something would happen and the hope that still it wouldn’t, there is much more space than one thinks. On that narrow, hard, bare and dark space a lot of us spend their lives.” — Ivo Andric, Serbian novelist and 1961 Nobel Prize Winner.

“In your pomp and all your glory you’re a poorer man than me/As you lick the boots of death born out of fear.” – Jethro Tull, Gregg Popovich’s favorite rock band circa 1973

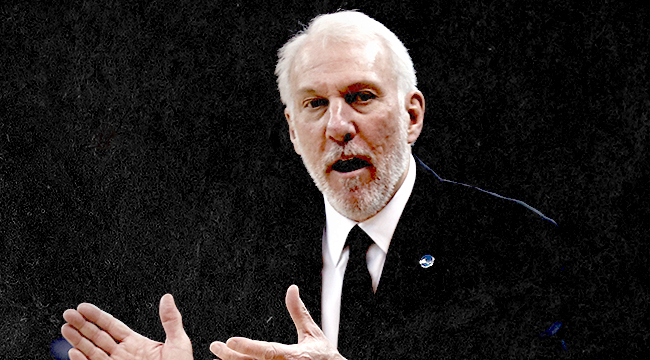

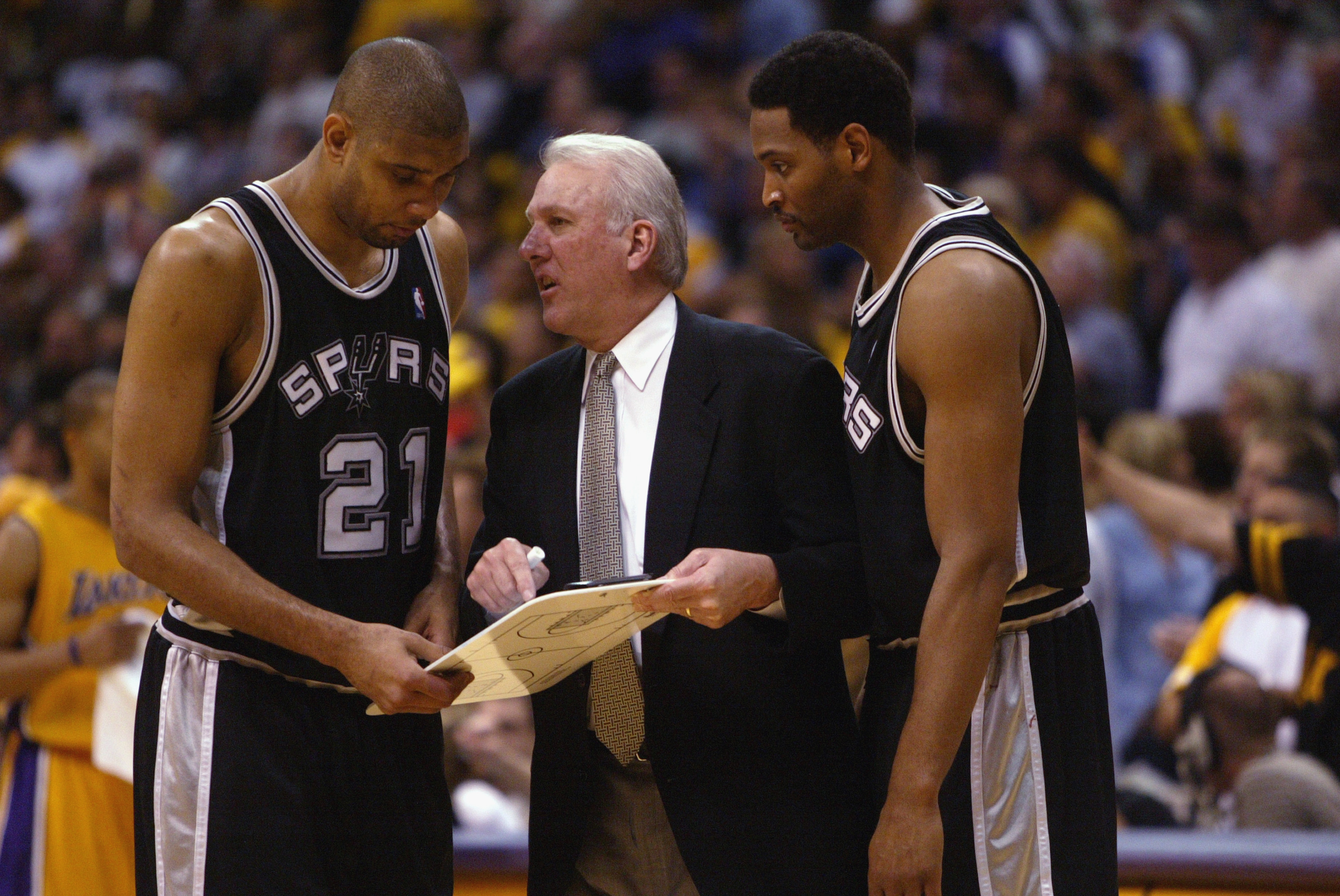

Before Gregg Popovich became the beatified basketball Gandalf, a five-time NBA champion, the most lacerating and eloquent anti-Trump critic in professional sports, and a viable candidate for the greatest coach of all-time, he had to survive the devil in Dennis Rodman.

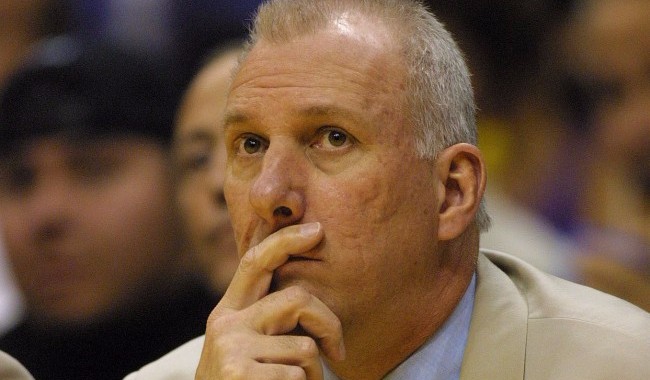

In hindsight, Popovich’s brief rivalry with America’s highest-ranking diplomat and chief hair bleach exporter to North Korea exists as a historical footnote. But in the spring of 1995, it threatened to sabotage the 46-year-old rookie GM’s professional career before he could gift Tim Duncan his first pair of Dockers.

We often overlook those Rodman years in San Antonio as a bizarre interregnum between when he first saw Demolition Man and those final three championships in Chicago. But during Popovich’s inaugural season, Rodman remained squarely in his platinum blonde prime, averaging nearly 17 rebounds a game, shooting 57 percent, consistently locking up the opposing team’s premier scorer, and being so integral that Jack Haley earned a roster spot just to be Rodman’s translator and chill surfer bro best friend.

During the regular season, the 94-95 Spurs had posterity securely in their scope, racking up a franchise record 62 wins, and finishing first in the West. But it all unraveled in the playoffs when Rodman’s chronic insubordination became a permanent distraction. He showed up late to practices and games, decamped for gambling and Goldschlager odysseys in Las Vegas, and maddeningly continued to insist that Pearl Jam was the greatest grunge band.

Willing to risk it all like Melo with a Hennessey-filled top hat, Popovich suspended Rodman for his antics. The Spurs somehow beat the Lakers, but Hakeem Olajuwon dreamshaked to victory in the Conference Finals, and the pride of Pace Picante Sauce ostensibly botched their best chance to win an NBA title.

In the offseason, the untested GM found himself at a crossroads.

On one hand, Pop still retained the finest pure rebounder in NBA history under a guaranteed contract. David Robinson was the reigning MVP and Sean Elliott was a young assassin good for 20 a night. Only one theoretical acquisition kept them from mounting a serious championship run the following season. On the other hand, Dennis Rodman had publically revealed that his nickname for Coach Bob Hill was “boner.”

“The city kind of embraced me, but what’s his name, Popovich, he hated me,” Rodman reflected on his time in the Alamo Dome. “He hated my guts because I wasn’t a bible guy. They looked at me like I was the devil.”

Obviously, Rodman’s inability to recite lengthy benedictions from the Book of Psalms was not the primary gripe. But it’s difficult to imagine two more antithetically opposed personalities than the ex-Air Force Cadet and the erratic power forward about to be cast in a Jean-Claude Van Damme vehicle as the flamboyant weapons dealer, Yaz. (Quoth Roger Ebert: “He does a splendid job of playing a character who seems in every respect to be Dennis Rodman.”)

Pop’s managerial philosophy was predicated on treating all 12 players by the same set of rules. Dennis Rodman blew off team huddles in the middle of the playoffs. So at the risk of everything that he’d ceaselessly labored towards in his previous four decades of existence, Popovich traded Rodman to the Chicago Bulls for Will Perdue.

You probably don’t remember Will Perdue. The best thing I can say about his hoops ability is that he really understood that he had six fouls to give. He was a lumbering goofus with a hamster haircut and the soft touch of a stonecutter. In an attempt to mitigate the loss of Rodman, Pop signed a washed Cadillac Anderson and Brad Lohaus, whose only notable career achievement was rivaling Mike Iuzzolino for worst player in NBA Jam.

Somehow, the 95-96 Spurs lost only one less game than the year prior. What should have guillotined Pop’s fledgling career wound up consolidating his power within the organization. He exhibited the fearlessness, savvy, and expansive vision that would become hallmarks of his success.

Every legend needs an origin story, and this is the moment when a pockmarked, Fantastic Sam’s-coiffed, neophyte who never met a suit he couldn’t mismatch first became Pop.

* * *

Gregg Popovich is a classic known unknown.

The Wikipedia contours of his life are easily researchable but the exact specifics are purposely vague. It’s presumably a vestige of the military secrecy that shrouded his early life. No attempts at mythmaking. No “Spurs Way” bestsellers expounding a bogus philosophy. No $100K speeches to sub-Mnuchin’s, searching for the leadership skills to artfully foreclose on your grandmother.

Consider that only four years separate Popovich from Pat Riley and Phil Jackson, but they essentially emerged from different centuries. During the ‘80s, the former served as the model for the “Greed is Good” anti-hero of Wall Street, and reportedly turned down the starring role. With Armani Suits and slip-n-slide hair, Riley famously embodied the Hollywood slickness of the Showtime Lakers. His subsequent facelifts of New York and Miami were similarly big budget bottle service operations. He even had his own Sega Genesis game.

Can you imagine a Greg Popovich video game? You’d never actually pick up the basketball but instead alternate among sketching weak side pick n’ rolls for Manu Ginobili in an animated wine cellar, vying to shut down press conferences by uttering the fewest syllables possible, and explicating Traffaut to Kawhi Leonard.

As for Phil Jackson, he bopped from transcendent generational talent to transcendent generational talent, and authored seven books that did everything but divulge his homemade recipe for sautéing peyote. When the Chicago Bulls hired the Zen Master as head coach, Popovich was just a year removed from the Division III ranks. If both Riley and Jackson were key role players on NBA championship teams, Popovich’s ascent was arduous, unglamorous and anything but preordained.

The offspring of a Serbian father and Croatian mother, Popovich was inherently fated to understand conflict. Popovich described the East Chicago neighborhood of his childhood to Sports Illustrated as working class and diverse with a “white family here, a Puerto Rican family there, a Polish, or Czech family over there.” His early heroes included the basketball players and coach at the powerhouse local high school, East Chicago Washington.

After his parents’ divorce, Popovich’s mother uprooted the family to Merrillville, then a mostly white semi-rural community of 15,000 people on the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Before the collapse of domestic manufacturing, U.S. and Inland Steel employed nearly the entire town, including Popovich’s mom, a secretary, and his stepfather, a plant administrator.

It’s strange to consider Pop as a young man.

You instinctively picture him popping out the womb white-bearded and tersely uttering epithets in four languages. But sepia photos exist of him in a stern crew cut and a narrow Isoceles triangle of a face. He loved Motown and was apparently a deceptively good dancer. An eternal underdog, he was cut from the Merrillville varsity as a sophomore but spent the entire summer playing pick-up in neighboring South Gary, the lone white boy hooping on 39th and Broadway.

He made the varsity the following season and walked around the hallways wearing ankle weights to fortify his leg strength. Maybe you knew someone like Pop growing up: the kid who dribbled a basketball to school and ran wind sprints at lunch. The guy whose house you’d visit and he’d be scrutinizing ESPN Classic in the off-season rather than play video games.

During his summer vacation from the Air Force Academy, Pop knocked on his high school basketball coach’s door every night, asking for the key to the gym. That’s a pretty rote tale in every would-be basketball hero’s rise — except that Pop used the gym to practice defensive slides for hours on end. Only two options exist at that point: a future in basketball or the insane asylum.

In a classic compromise between discipline and lunacy, the lightly recruited teenager chose the military. Coached by his mentor, future Spurs assistant coach Hank Egan, Pop failed to make the varsity until his junior year. Continuing the pattern, he wound up the team captain and leading scorer (14.3 ppg) as a senior. A Soviet Studies major fluent in Russian, his course load included advanced calculus and astronomical, electrical, and mechanical engineering.

Pop later told a reporter that he got Ds. I’m pretty sure that he was being sarcastic, but who knows. He’s made a career out of keeping people guessing.

The immediate post-graduation years are murky. He received an active commission on June 3, 1970 at the height of Vietnam and the Cold War. Assigned to the 659th Support Group in Sunnyvale, California, Pop’s initial assignment was within the highly classified Air Force Satellite Control Facility, which received oversight from the Space and Missile Systems Organization—an organization that controlled the military’s expeditions into outer space.

Proximity to Napa Valley incubated a lifetime love of wine that eventually culminated in a 3,000 bottle collection and a prominent investment in Oregon winery A to Z Wineworks. On the basketball side, he captained the U.S Armed Forces team that won the 1972 AAU Championship, which earned him the opportunity to try out for the 1972 Olympic Team and the Denver Nuggets.

He was cut both times by Larry Brown, for whom Popovich would later become so close that he’d serve at the best man at his wedding.

During his half-decade in the armed forces, there was intelligence training and a failed application for a highly classified government job in Moscow. His final foreign stint was at Diyarkbakir Air Station, a forsaken citadel in southeastern Turkey on the Iranian and Syrian border, where massive radar antennae monitored Russian ballistic missile launches. In recent years, the region withstood an invasion from Islamic militants.

According to a 2001 feature in the Turkish newspaper, Radikal, when Popovich first descended the stairs of the military transport, a stranger bum-rushed him, yelping euphorically and maniacally hugging him.

“I didn’t understand what was happening,” Popovich said. “I then learned it was the lieutenant I was replacing.”

By contrast, a quarter century in San Antonio sounds glorious. These experiences supply the intangibles that can’t be quantified. If worldliness was the principal criteria for basketball success, than David Blatt surely wouldn’t have flamed out so quickly in Cleveland. But you can’t discount that impact on Popovich, who found himself haggling in the town souq and invited to devour roasted lamb and hummus at private homes.

This experience prepared him to coach a Spurs roster that has historically doubled as a de facto United Nations, but also opened him to the possibility of how many great players existed outside of the continental 48. It offered a deeper education and appreciation of cultural differences and inured him against the hysterical xenophobia sweeping the present moment. The concept of Pop as internationalist leader starts here.

Still, the details of that assignment remain opaque. A longtime Popovich comrade named Arlie Pierce was once quoted about receiving but one phone call from Turkey. In typical Pop fashion, he offered no revelations about military life or political intrigue. The chief thrust of the call was to insist that he purchase the new Jethro Tull record.

* * *

In contrast to the human bone spur leading the country, Popovich left the military with a small arms marksmanship ribbon (given to experts with military issue-handguns and/or M-16s), a National Defense Service Medal (awarded to all military brass serving during the Vietnam War), the Longevity Service Award Ribbon (in recognition of eight years of honorable service) and finally, the Air Force Commendation Medal (bestowed upon personnel who “distinguished themselves by meritorious achievement and service”).

For his final deployment in the Air Force, Popovich returned to Colorado Springs, where he assisted Egan, received a Masters in physical education and sports sciences, and coached at the Academy’s preparatory high school. No one remembers those mid-70s Air Force teams for good reason; the squad’s record generally hovered a few games or below .500 and it’s very possible that Popovich could’ve remained there until Egan left for a head coaching gig at the University of a San Diego in 1984.

Except for that in the waning years of the Carter era, an Air Force assistant received an offer to coach at Pomona-Pitzer, an also-ran Division III liberal arts college about 30 miles east of Los Angeles. He turned it down, referred Popovich, and within due time, Popovich was living with his family in a dorm, working out of a converted storage closet, teaching physical education, driving the school van, directing intramural water polo, serving on a women’s committee and chairing an investigative committee into fraternity abuse.

He regularly invited his players to dinner for something inauspiciously called “Serbian Tacos.” In his first year, they went 2-22 and lost to Cal-Tech, arguably the worst sports program in America.

“He became a great X and O guy because he’s studied the game at every level,” Golden State Warriors assistant coach and former Cavs and Lakers head coach Mike Brown, who served as Popovich’s assistant for many years in San Antonio, says. “You can’t underestimate the fact that he started his career at the Division III level, where you don’t have the necessary athletes or players to toss the ball to one guy who can win the game. Guys play zone, almost everyone is equally talented, and you really need to learn to execute if you want to win games.”

I played baseball at Occidental College, a conference rival of Pomona-Pitzer, and attended nearly every single basketball home game. As chimerical as it may sound to you that a guy pushing 40 and still coaching DIII would eventually win five NBA championship rings, it’s even more astounding in context. It’s not that the caliber of play was so bad. (It was high level for low-level basketball.) But it’s just the sort of sports Pleasantville where people never leave. They run programs for 20 years, settle into a quiet liberal arts college life, and accrue impressive retirement benefits. Popovich did not blend, although his years at the school certainly contributed to the breadth of his knowledge and intellectual rigor.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kt7MJQlY6lc

“I was in awe of the brilliance of that campus,” Popovich was once quoted as saying.

Stories have circulated over the years, particularly from Jordan Conn’s excellent 2015 Grantland article about “Poppo’s” stint with the Sagehens. He once forced the players to shoot free throws in their underwear. He punched a chalkboard and hurled chalk at one of the stars. Even a Mervyn’s employee would’ve scoffed at his garish sport coat and tie collection.

Yet Pop turned a perennial doormat into a league champion, a Bad News Bears type-arc that usually only exists in the movies. Even then, Buttermaker doesn’t go on to become Tommy Lasorda. But in this instance Pop did, but with a more profound appreciation of Sangiovese red wine.

“There are at least four qualities necessary to be a great coach,” Basketball Hall of Famer Larry Brown, who remains the only one in history to win championships at the college and professional level, says. “No. 1 is that you can’t be afraid to be yourself or afraid to coach guys. When you walk into an NBA locker room in about half an hour, they know if you can coach a little bit—and that’s obviously important. The third thing you have to get it through to players that you can make them better because if you make them better, it helps them win and gives them the chance to make more money.”

“The fourth and the most important thing in my mind,” Brown continues, “that separates good coaches from great ones like Pop is making it so the players know you care. He’s brutally honest, but he’s brutally fair.”

It was Brown who in 1988 plucked Popovich out of relative obscurity and offered him a spot as Spurs assistant coach. Their bond had been solidified during the previous year when Pop took an unpaid sabbatical from Pomona-Pitzer to learn from Dean Smith at North Carolina and Brown at Kansas.

In between his stints with the Spurs, Pop assisted Don Nelson in Golden State — whose early reliance on small ball, three point shooting, and floor spacing seems visionary today. For someone of modest origins, Popovich’s desire to learn from the best and willingness to sacrifice everything in the process ultimately helped him achieve one of the finest coaching pedigrees in all of basketball.

If those words on Popovich seem unusually sentimental coming from the infamously savage Brown, it speaks volumes about the underlying psychological tango of basketball’s player-coach relationship. If you read quotes from his Pomona-Pitzer mathletes and his San Antonio Spurs, the lone parallel is Popovich’s ability to relate and empathize with them on a human level.

In the prevailing basketball cliché, Pop has the gift of getting players to “buy in.”

This is why he and Tim Duncan would go swimming with the dolphins in the Virgin Islands and call each other veritable soulmates. It’s why he could woo LaMarcus Aldridge over a host of more glamorous suitors and harness a flashy teenage French point guard/aspiring rapper to play within the confines of the-then staid San Antonio system. He could integrate the notoriously volatile Stephen Jackson into a crucial component of a NBA championship team even if he couldn’t stop him from going full Pimp C Port Arthur-style on Serge Ibaka.

In recent years, he’s taken the team to see Hamilton, helped set up the first San Antonio screening for Birth of a Nation (which Parker executive-produced), brought in Tommie Smith as a guest speaker, and gifted the team copies of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me.

As the Rodman fiasco proved, a single malcontent can almost torpedo a franchise. Yet Popovich is amidst what will inevitably become a record-setting 21st straight winning season. There has been no drama, no scandal, no acrimony spilling into the press, and no tell-all exposés. All family business is kept within the family. Some of the evidence to his genius stems from what hasn’t happened.

It’s not just that he and R.C Buford are immensely gifted at scouting and excavating talent from the corners of the earth, most famously scooping Manu Ginobili with the 57th overall pick. It’s also that they can read things in players that no other coach or G.M. can see. Sometimes, not even the player can see it. In the 2011 draft, Kawhi Leonard was selected No. 15 behind Jimmer Fredette, Jan Vesely, and Bismack Biyombo. They acquired Danny Green from the D-League and turned him into one of the league’s most formidable defenders and three-point shooters.

At this point, the Spurs are like Menudo in 1988. You can put anyone in there and you’ll win a Latin Grammy or 60 games, whichever comes first.

“He’s very good at talking someone into being great,” Shea Serrano, the world’s greatest Spurs fan, one-time Dime Podcast guest, and author of the best-selling book Basketball (and Other Things), says. “Between 2012 and 2014 you watched him do it to Kawhi Leonard. Before that, he took Tony Parker from a guy who could get to the rim but couldn’t shoot into a Finals MVP and Hall of Famer. He turned Danny Green into an assassin. No one has developed more good players than Pop.”

* * *

If you ask Pop about his innovations to the game of basketball, he’ll inevitably respond with some variation of “I drafted Tim Duncan. That’s about it.” It’s a sly evasion and intentional deconstruction of the mythology that inevitably occurs when you have a ring for each finger on your right hand. And realistically, he could have eight championships if not for a Derek Fisher miracle three-pointer, a missed Tim Duncan layup against the Heat, and an inane Manu foul on a driving Dirk Nowitzki in 2006.

This insistence on deflecting credit towards his players is partially what endears him to them. In a culture and sport overrun with egomaniacs eager to burnish their cult of genius, Pop wants none of it. He rarely grants one-on-one interviews, almost never talks about himself, and refuses to cash in on his celebrity. His strongest gift and biggest weakness seems to be an allergy to telling anything but the unvarnished truth.

It’s been 21 years since he first became head coach of the Spurs. Most of this season’s rookie class hadn’t left the crib when Pop won his first title. And aside from that first fluke season where injuries limited David Robinson to six games, no Spurs teams has won fewer than 50 games.

It’s death, taxes, and the Spurs.

Of course, it helps when you have Tim Duncan, but last year’s squad won 61 games and reached the conference finals. Plenty of analysts forecast that this year would commence the Spurs gradual decline, and they’re currently 4-4 with wins over the Timberwolves and Raptors. All this without Kawhi Leonard and Tony Parker. They’ve only spent 48 total days with a losing record in the past 20 years. Pop’s only real rival for system efficacy in the professional sports world is Bill Belichick and the Patriots, except that he’s managed to do it without committing light treason.

As late as 2001, articles were still being written claiming that the “conventional sportswriter knock on Popovich remains that he’s at best a mediocre coach who has the good basketball sense to stay out of the way of his star players.” By 2017, it’s time to seriously debate whether Popovich is the greatest of all-time.

Consider the recent failure of his long-time rival, Phil Jackson, in New York. Despite his inarguable dominance with the Lakers and Bulls, Jackson tried to shoehorn the Triangle Offense into a team that lacked the proper personnel and a league that had passed it by. In contrast to the more dynamic space and pace modern offense, it felt antiquated. That intransigence revealed Jackson’s inability to adapt to the contemporary game. By contrast, Popovich has won championships in distinctly different eras, seamlessly tailoring his schemes to the skillset of the talent.

Not to mention that even a respected NBA champion like Doc Rivers failed to successfully pull off the task of being a GM/Coach; Popovich remains the last to artfully pull off that hybrid.

Those Duncan and Robinson Twin Towers teams resembled the NBA equivalent of Pop’s old favorites, Jethro Tull: plodding, virtuosic, and blandly effective. In this latest iteration, they’re closer to Kraftwerk: wide-open and unemotional, swift, robotically funky, and monochrome. Masters of restrained improvisation.

If the changes in the game have weeded out more refractory minds, Popovich has eagerly welcomed new innovations in analytics, player training, and style of play. He’s become a master of both traditional inside-out basketball and corner three heavy, high efficiency play that slants closer to Europe — no doubt aided by the addition of legendary Italian coach Ettore Messina to his coaching staff. But it’s not just his ability to adjust from season-to-season; it’s game-by-game and play-by-play. It’s the same fearlessness and experimental streak that allowed him to win by 39 in a deciding Game 6 in last year’s playoffs.

Faced with the loss of Leonard and Parker, he reverted to his vintage style of dual big man basketball and slaughtered the stunned Rockets on the road.

“Here’s a man who has had multiple success at the highest level, but has adjusted and adapted to today’s athletes,” Mike Brown, who returned to help out the Spurs two years ago before joining Steve Kerr’s coaching staff, says. “It’s phenomenal how he’s still the same person but changed the way that he gives messages to the team based on the feel of the group and the way that today’s young athletes are.”

“Of course,” Brown adds, “the game is different today from the playbook standpoint, but due to social media, your communication skills have to be totally different. And Pop has done a fantastic job of adapting and adjusting the way that he communicates.”

You can point to any number of other contributions that burnish Pop’s legacy. He hired former WNBA star Becky Hammon as the first full-time salaried female coach in NBA history. Eliciting David Stern’s ire, he pioneered the art of resting players during the regular season, undoubtedly allowing them an increased longevity. To scan the modern NBA is to see a legion of Popovich disciples: Mike Budenholzer in Atlanta, Steve Kerr in the Bay, and Brett Brown in Philadelphia. Sam Presti advanced from being a one-time Spurs intern to the General Manager of Oklahoma City. Dell Demps left a post as vice president of basketball operations in San Antonio to run New Orleans. That’s merely the shortlist.

But if Popovich has long ranked among the best ever, it’s only in the last few years when his all-time greatness has become readily apparent. This is a matter of semantics, sure, but greatness goes beyond a wins and loss record and championships. It’s about capturing the popular imagination and serving as an inspiration.

And unless you were a diehard Spurs fan, it was difficult to love the franchise. They were certainly to be feared and respected, but they were the 60 Minutes of the NBA: long-running, dependable, fundamentally sound, and dull as that ticking clock.

It started to change when the point of attack shifted from Duncan to Manu and Parker, and then to Kawhi. The pace accelerated; the Spurs became fun to watch, a startling transformation akin to Dorothy stepping into Oz and everything going into Technicolor. Meanwhile, the Heat emerged as a super-team counterweight that conformed to reductive binaries of small market vs. big, old school versus millennial, yachts and banana boats versus the 20-year-old jalopy that Kawhi still drives. But most of all, the transformation became complete when Popovich began to attack Donald Trump and the terrifying chaos wrought by that toxic cheddar charlatan.

In a paradoxical way, the abject racism and grotesque mean-spiritedness of Trump has brought out the best in Pop. For the first time, the world has witnessed the full panorama of intelligence, depth, and eloquence that has been largely limited to the Spurs locker room and practice facilities for the past two decades. You no longer have to love the Spurs or even basketball to love Pop. In his slashing diatribes against Trump, he’s emerged as America’s conscience—the wise elder we need, not the senile Lear in office — a military veteran with the wisdom, insight, passion, and credibility to indict the maddening lies and stupidity that have become endemic.

After all, his nickname is another word for dad.

Just re-read the blistering statement he recently gave to The Nation:

“This man in the Oval Office is a soulless coward who thinks that he can only become large by belittling others. This has of course been a common practice of his, but to do it in this manner—and to lie about how previous presidents responded to the deaths of soldiers—is as low as it gets. We have a pathological liar in the White House, unfit intellectually, emotionally, and psychologically to hold this office, and the whole world knows it, especially those around him every day. The people who work with this president should be ashamed, because they know better than anyone just how unfit he is, and yet they choose to do nothing about it. This is their shame most of all.”

Or maybe you prefer his trenchant comments on the nature of whiteness, racial inequality, the righteousness of Colin Kaepernick’s protest, the horrors of Charlottesville, the enduring national stain of slavery, or his recurring nightmare that America is slipping into a state of Roman decay.

“What he’s been saying is extremely important,” Mike Brown says. “There’s only a couple guys willing to risk serious backlash by speaking out on these topics loudly and say what 95 percent of the NBA and many other Americans are thinking. It gives guys like myself and other ‘young coaches’ with less experience or success, the opportunity to sit back and say ‘way to go Pop.’ We feel like you’re our voice too. And that’s something that over time will lead to change.”

In an era where it feels like nothing matters and everyone has gone insane, Popovich has stepped into the spotlight that he’s long shunned to become a rare beacon of sanity, humanity, and insight. Forever fearless. After 20 dominant seasons in which he ensured that his players had their moment, the time has finally come for his.