Aside from family, and maybe in some cases more than family, my uncle Bobby loves two things above all others in this world: Washington-Baltimore-area sports, and Bruce Springsteen. I don’t mean love in the way some people love Girl Scout cookies or old boots. I mean love like this: He’s in his 60s now, still wears an earring like Springsteen, and spends summer nights as an usher helping people find their seats at Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

My mother and Bobby were two of five children, but when their older brother Lonnie died unexpectedly in his 30s long ago, they became two of four. That’s how I knew them when I was growing up in the 1980s: Janet, who lived in Ohio and sent us Buckeyes gear every Christmas; Mary Anne, who loved the beach and built a tiki bar in her backyard; and Bobby. He’d shoot hoops with me and my brother for hours, play records loud, and always had the best stories about meeting our sports heroes.

We rarely had everyone together, but when we did, we were in my grandfather’s house in Silver Spring, Maryland. Granddad loved his golf, his Redskins, his Italian opera, and his marching bands (they were all his), so we’d go back and forth between listening to Pavarotti and “Hail to the Redskins” while the adults drank and told stories until someone cried.

Occasionally Bobby would plop a Springsteen album on the record player when the old man wasn’t looking, but my point is sports and music often existed in the same room in our family. They made sense as a couple, each floating into our heads as a series of high notes and low notes, stories and characters.

That’s carried through to today. Every year on the first Sunday of NFL season, a friend sends me a text message before 7 a.m. with an audio file of “Hail to the Redskins.” Every year on baseball opening day, I’ll blast, “Orioles Magic.”

And every year at the start of the NBA season, I’ll pull up the YouTube of “Bullets Fever.”

The last one starts like this: “Bullets Fever! Happens to me every year.”

***

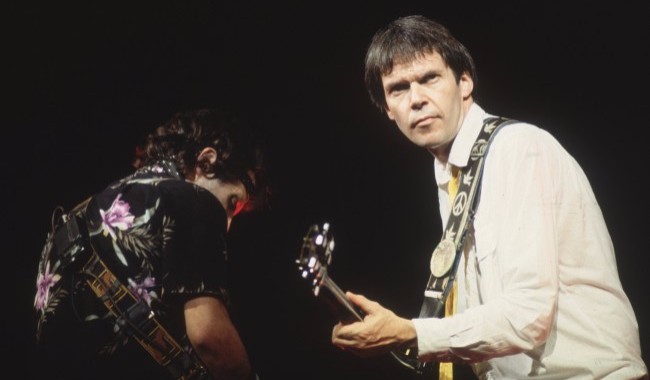

Forty years ago this spring, on the final night of the NBA season, a young rock-and-roll musician was living alone in a one-story rental home in the leafy neighborhood of Garrett Park, Maryland, just outside of Washington. Nils Lofgren had toured with Neil Young and recorded several records of his own by then, but he had no idea he’d one day join Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band and put together a career that would span a lifetime.

The Washington Bullets spent much of that season trying to figure things out, too. They had several injuries and fluttered a couple of games above .500, sometimes a few more, always in danger of missing the playoffs. But in the final game of the regular season, on April 9, 1978, they took down Julius Erving and the 76ers, the top team in the East, to hop from fifth seed to third seed, securing home-court advantage in the first round of the playoffs.

Lofgren had been a fan of Washington sports since his family moved from Chicago to the D.C. suburbs when he was eight. His father, a mild-mannered Swedish man, devoted his career to improving the safety of automobiles and took a job with the nonprofit Insurance Institute for Highway Safety in Arlington, Va. Some of Lofgren’s earliest memories are of watching ads that promoted seatbelts, with racecar drivers like A.J. Foyt pointing their fingers at cameras to tell the world that they wear their belts, too.

Sports and work and music always mixed in the Lofgren home. Nils first picked up the accordion when he was five and trained on it for nearly a decade. He learned guitar in his teens, and in 1968, as a high school senior, he formed the band Grin. One night, Lofgren snuck backstage after a Neil Young show to meet the star. Somehow he convinced Young to let him play a few notes on guitar. Young saw promise in the kid and later invited Lofgren to California to live in his rental home. In 1970, Young asked Lofgren to play piano on the band’s new record, After the Gold Rush. One of Lofgren’s most noticeable influences is in the song “Southern Man,” where he plays the piano with a bit of an accordion artist’s touch, giving the keys portion a polka hop.

After touring with Young, Lofgren went back to Grin. In 1974, the band lost its record deal, split up, and Lofgren went solo. Critics loved him and the small crowds embraced his passion on stage (Lofgren, a 5-foot-3 guy who was a gymnast as a kid, is famous for doing backflips during shows), but commercial success eluded him.

That’s where he was in his career that night in the spring of 1978, a talented musician about to turn 27 years old, wondering if he was washed up, feeding off of every basket the Bullets made.

***

He wrote “Bullets Fever” that night. The next day he called a friend, Bob Dawson, who had a studio. Lofgren laid down an initial track, then played all the instruments and sang (guitars and piano and harmonies). Dawson made the mix and ran off 25 cassettes. The next day, Lofgren opened the phone book and wrote down the addresses of radio studios around Washington. He drove each cassette to a different studio and asked that it land on the desk of the program manager.

“And sure enough, they kept winning, and somebody started playing it, and next thing you know, it was like the most requested song on local radio,” Lofgren told me recently. “God bless ’em. They kept winning.”

For weeks, Lofgren’s high-pitched voice piped into cars around the beltway:

You gotta be a fan from old D.C.

To know what the Bullets mean to me.

To see them get up and go all the way

For me, Bullets Fever is here to stay!

Not exactly “Like a Rolling Stone,” but still catchy. Bullets owner Abe Pollin took a liking to it and invited Lofgren to meet with him. A few days later, Lofgren was walking around the Capital Centre, the old swoop-roofed arena out in Landover, Maryland, where the Bullets and Capitals played for decades. The meeting was at 10:30 a.m.

“I looked like a homeless person,” Lofgren remembers. “Disheveled and just very casual, kind of in my own world.”

Pollin told Lofgren he loved the song, but he had some questions about how it came together. Who wrote it? “I wrote it,” Lofgren said. And who sang it? “I sang it.” And who are the musicians in the background? “Just me.” Wait, what do you mean? “I played everything.” Well, who are the girl singers? “That’s not girl singers. I’m singing falsetto. That’s me.”

By the end of the meeting, Pollin and Lofgren agreed to press 1,000 45s and donate the proceeds to Pollin’s leukemia foundation. They sold out almost immediately. An original copy of “Bullets Fever” remains a rare find because, of course, Lofgren had to update it.

After the Bullets knocked off the Spurs in the second round and surprised the Sixers in the Eastern finals, Lofgren added lines such as, “Got the Doctor and the Iceman,” references to the Sixers’ Julius Erving and Spurs’ George “The Iceman” Gervin.

Then, after the Bullets beat the Sonics in the finals to give Washington what remains its only NBA championship, Lofgren added the kicker, “Seattle was stuuuunnnnnned.”

On June 8, two days after the final game, Jimmy Carter invited the Bullets to the White House. In the official archived notes from that day, Carter’s talking points remind him to say that the last time a Washington team won a world championship was in 1942, when the Redskins won a title during the Roosevelt administration.

“This town has Bullets fever,” said the president.

***

It’s November, and they say the Washington basketball team has a chance to play in June this year. They know, these people who know these things, what will happen in the West, that the Warriors simply have too much for anyone else, and yes, that means even you, Houston. But what of the East, the land where LeBron does it all and the Celtics may finally answer the call and the 76ers have the best rookie in the league without the baggage of Ball?

(Sorry. Felt like this essay needed a rhyme.)

The Wizards have all five starters back, these experts will tell you, from the team that took the Celtics to Game 7 in the Eastern Conference semis last year. They could do it, says FiveThirtyEight, which gives them an 11 percent chance of winning the East. They could win 50 for the first time since 1978-79, the other sites say.

I can’t claim to know as much as the experts do on the matter, but I’m far less optimistic. Same as I’m less optimistic that Kirk Cousins can lead the Skins deep into the NFL playoffs. Same as I’m less optimistic that the Capitals will ever beat the Penguins in the NHL playoffs again.

It’s easier this way.

I learned from an early age to brace for the worst from Washington sports. And while we don’t have it as bad as others, times are tough, man. No team from Washington has advanced to the conference finals of its sport since 1998. I’m still a die-hard Orioles fan (Washington didn’t have a baseball team when I grew up), but the O’s aren’t riding in many parades these days, either. They rolled into the ALCS three years ago, only to get swept by the Royals. I drove up from my home in Charlotte for Game 1 of that series.

The O’s lost in extra innings, and when we couldn’t find a cab afterward to take us back to my brother’s home in Baltimore’s Canton neighborhood, Kenny screamed right there in the October night, “Why doesn’t anything just GO RIGHT?!?!?” And as crazy as that might seem to some of you, I know someone from Maryland just read that line and nodded and said, “Yep, been there.”

I’ve lived in North Carolina for almost 20 years now, and although my sports teams keep me connected to home, I’ve grown to appreciate other things. My house is less than two miles from the homes of the Hornets and the Panthers, and they are a couple of mostly inoffensive lots, so I hope they win. When they do, great! When they don’t, I still eat breakfast the next day.

Mostly, though, I’ve tried to spend more time and money on music, for the obvious reason that concerts are less likely to disappoint.

I’ve seen Springsteen nine times, far less than most of his fanatics, and far-far less than Uncle Bobby. But I’ve seen him enough to get it. I own just about every record and stay up deep into the nights re-reading the lyrics to try to find out what he’s really saying. That’s the connection Springsteen makes with his fans; in just a few words, he makes you want to know what he knows.

Seven years after “Bullets Fever,” in 1984, Springsteen asked Lofgren if he wanted to join the E Street Band on a tour for a little record called Born in the U.S.A. It seemed like a good idea at the time, so Lofgren did, and suddenly he was part of one of the biggest rock and roll tours ever. And in the 33 years since, Lofgren has stayed by Springsteen’s side whenever the Boss has asked him to be there.

Fans of Bruce have favorite members of the E Street Band. Many claim Little Steven on guitar or Max Weinberg on drums, and millions claimed Clarence “Big Man” Clemons, rest his soul. But to folks like me — and by that, I mean short people who have a thing for losing sports teams from the Washington area — Nils is our guy.

So after listening to “Bullets Fever” this October and reading the predictions, I reached out to see if he’d talk to me about the song and old times. He called the Monday after the Redskins lost to the Cowboys in Week 8. Go figure.

***

One of my favorite stories from the conversation wasn’t about the Bullets, but the Celtics.

The first three shows of the Born in the U.S.A. tour were in St. Paul, Minn., in June 1984. One night, an extremely tall man from Minnesota came backstage and introduced himself to Lofgren as Kevin McHale. The two started a friendship that continues today.

In 1986, McHale invited Lofgren to hang out with the Celtics during their NBA Finals run against the Rockets. The Celtics won the first two games in Boston. The second of those games was on a Thursday, and Games 3 and 4 were scheduled for Sunday and Tuesday.

On Saturday night, a few players and Lofgren gathered in the lobby of the Westin in Houston. Rick Carlisle, then a guard for Boston and now the head coach of the Mavericks, could play a little piano. Lofgren and Carlisle scratched together a song called “Rocket Blues” on hotel stationery and played it to a few laughs. They never released it and nobody had cell phone cameras back then, so Lofgren went on with his life, believing there was no record of the song.

A few years ago, he got something in the mail from Carlisle: It was the piece of stationery, with loopy handwriting and the lyrics they’d written that night. Lofgren has it framed in his house, and he sent a picture of it to me and helped me translate the handwriting.

The lyrics throw some 1980s-style bombs the Rockets way:

Goin’ down to Houston,

And play some basketball.

The Rockets may be standing,

but their backs are against the wall.

You can jump, you can run;

Anyway, you’re goin’ down.

Hey by midnight Tuesday,

We could be paintin’ this town.

It’s going to be a fight;

They have to get mean

Hey by midnight Tuesday,

We might just paint the town green.

The Rockets wound up winning Games 3 and 5, but the Celtics won the series in Game 6 back in Boston, and they grabbed their green paint there instead.

***

Music and sports both have a way of serving as markers in a lifetime. We don’t forget where we were for our first concert, and we don’t forget where we were when our guys finally beat the other guys. My uncle Bobby remembers that he and his sister, my aunt Mary Anne, were at the Stained Glass Pub in Silver Spring the night the Bullets beat the Sonics in Game 7 in 1978.

Players from that team still shout Lofgren’s name when they see him somewhere, like when Mitch Kupchak hollered it from the aisles during the Final Four last year in Phoenix.

“The Bullets run, people that were right in the thick of it, that kind of stamps you like a great song,” Lofgren says. “And it never quite goes away, what you felt and what you went through watching your team.”

Lofgren and his wife, Amy, live in Scottsdale with their four dogs. His father died several years ago, but his mother just celebrated her 90th birthday last March. She still lives in the Washington area, and so do his brothers. He hopes to get back there next year on tour for a new solo album he’s been working on this fall.

Lofgren notices time passing in other ways. He had both hips replaced in 2008, a surgery that brought an end to his pickup basketball days. (He was famous for finding 3-on-3 games in just about every city, and despite the fact that he’s 5-foot-3, he often was tasked with guarding the other team’s best player.) And lately, he’s seen too many rock and roll friends pass away too early.

“Me and Amy, we’re getting more depressed every day about losing Tom Petty,” he says.

He sees good things coming, though. He and Amy are fans of Bruno Mars and other young musicians, and the NBA always gives him hope, especially now, with stars and coaches speaking out more often on issues that face the country. Lofgren, like Springsteen, has never been a “stick to sports” or “stick to music” guy. People, even famous people, are more complex than that.

“When you’re looking at more famous sports and music figures,” Lofgren tells me, “we could take as many as possible to keep lighting the way.”

Springsteen’s on Broadway this fall, so Lofgren’s spends his time at home working on the album and another fun project called “Blind Date Jam.” The general idea is this: Lofgren gets a few of his musician buddies together, someone throws out an opening riff, and they go from there. No practice, no notes, just jamming and playing off each other. The show is recorded and released as a digital video, available for download. The new show is scheduled for a Nov. 17 release.

“It’s a bit raw and reckless,” Lofgren says. “The theme is to not think, just react.”

Lofgren says lots of sentences like that, sentences that could be used either for sports or music. And he makes sure to add “the great” in front of special people — it’s “the great Kevin McHale” or “the great E Street Band” or now, one of his favorite athletes to watch in Arizona, “the great Larry Fitzgerald.”

He splits his attention between the Redskins and the Cardinals. He performed at halftime of the 2009 Super Bowl, just seconds after watching the Steelers’ James Harrison intercept a pass and take it back 100 yards against Arizona.

“I was looking at the TV like, ‘No! No!’” Lofgren says. “And someone banged me, one of the road men, and said, ‘Nils! … You gotta go now!’ I’d forgotten I was playing the halftime show of the Super Bowl.”

He tries, like we all do, to avoid letting little things like sports get to us, but sometimes they do. After watching the Cowboys beat the Redskins the day before our conversation, he thought back to his dad, the mild-mannered Swedish man whose life goal was to get a seat belt law passed to save lives.

“By the third quarter, the Redskins would be underachieving. I still remember my father standing up off the couch,” Lofgren says. “And he’d just wave his arms at the TV and go, ‘Ahhhh,’ just in disgust and he’d walk out of the room.”

I don’t know a Skins fan alive who hasn’t done the same thing.

***

The story my family tells every year is the one from Thanksgiving 1974, when Clint Longley replaced an injured Roger Staubach and led the Cowboys back from 13 points down against Washington. My grandfather stood up off the couch and walked over to the food my mom had prepared and shouted, “Thanksgiving’s off.”

I wrote about that story for another publication a couple of years ago around Thanksgiving. My aunt Mary Anne, especially, laughed when she read the piece. She had a great sense of humor about things like that.

Mary Anne died late last April after playing a few years of good defense against cancer. We all traveled back to Maryland for the services. The wake was on a Thursday night in a small church, and the whole place was decorated with pictures of her. In most of them, she was wearing some kind of outfit supporting a Washington-area team. Mom and Janet and Bobby, now the three of them, greeted friends and family and sniffled into tissues. Then we went back to a Hilton Garden Inn just south of Frederick.

We all changed and met in the hotel bar.

“Hey, can you turn on the basketball game?” Bobby asked the bartender.

The Wizards were down two games to none to the Celtics in the Eastern Conference semifinals. But that night, for some reason, they went on a 22-0 run in the first quarter and never stopped kicking their ass. We smiled and cheered and, when it was over, the adults drank and told stories until someone cried.

The Wizards won the next game, too, then split the next two, to force a Game 7. The day before the game, Lofgren released a short, new version of “Bullets Fever,” updating the name of the team and a few lines: “Wizards fever! We’re off to Game 7 now,” he sings. “For the Eastern Title, come on and get the job done.”

And then … of course … they lost … again … adding to the long streak of Washington playoff disappointments. That streak will surely come to an end this year, right?

Michael Graff is a writer in Charlotte. He can be reached at michaelngraff@gmail.com.