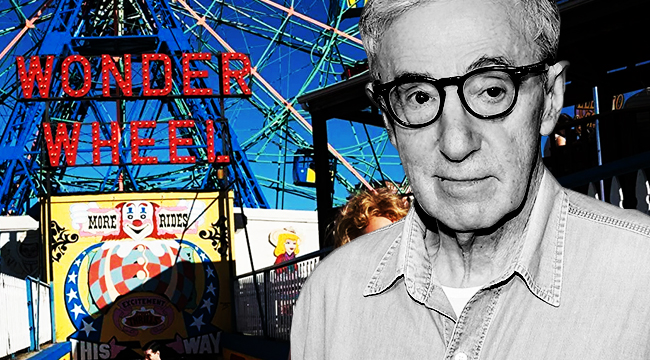

On Dec. 1, his 82nd birthday, Woody Allen’s 47th feature film, Wonder Wheel, will be released. His 48th feature, A Rainy Day In New York, just wrapped a two-month shoot in New York City last month. Superficially, at least, it appears as though Allen’s career is proceeding as it has for almost 50 years. And yet, outside of the unchanging bubble that Allen has built around himself, filled with Dixieland jazz music and insufferably bourgeois white people, there are signs that his troubling past might finally pose a problem for his film career.

While Allen worked on A Rainy Day In New York, his former collaborator Harvey Weinstein was swiftly swept out of Hollywood after dozens of women accused him of sexual harassment and assault. Weinstein’s demise was hastened in part by the reporting of Ronan Farrow, Allen’s estranged son, who even as a young boy seemed to loathe his father. (Allen reportedly reciprocated those feelings, referring to Ronan — then known as Satchel, his given first name — as “the little bastard” when he was just a baby, according to Vanity Fair. Later, when young Ronan kicked Allen, his father twisted the child’s leg until Ronan screamed, and threatened, “Do that again and I’ll break your legs.”) A month later, one of Allen’s highest-profile admirers, Louis C.K., suffered his own professional implosion in the wake of sexual misconduct allegations from five women. Now, C.K.’s new movie, I Love You, Daddy, an obvious homage to Allen’s Manhattan, is in jeopardy.

If this were a Woody Allen film — a philosophical, morally ambiguous thriller descended from Crimes And Misdemeanors and Match Point — this would be the part of the story when the protagonist would start to worry about whether his own life was about to turned upside-down by a transgression that he has, for now, successfully covered up. Except with the real-life Woody Allen, you suspect that this sort of rueful, middle-of-the-night introspection might be considered unnecessary.

The fact is, Woody Allen has been hiding in plain sight as a credibly accused molester of his own adopted daughter, Dylan Farrow, for 25 years. And yet, in that time, Allen has made 26 films and one (terrible) Amazon TV series. He’s also been nominated for nine Oscars, winning one, for writing 2011’s (kinda bad) Midnight In Paris. And he’s collected numerous lifetime achievement awards, from the Directors Guild of America, the Cannes Film Festival, and the Golden Globes. Woody Allen, clearly, has had little to worry about for decades.

Could that change in 2017? If ever there was a time for Allen to face the music — if not legally, then at least via an eviction from the mainstream film industry — you would think it would be now, as the dominos around him continue to fall. But then again, maybe not. The problem with the Woody Allen story is that it remains essentially unchanged: he was accused in 1992 of digitally penetrating Dylan in the attic of Mia Farrow’s summer home, when the girl was just 7. This allegedly occurred after years of inappropriate behavior by Allen toward his daughter. According to a 1992 Vanity Fair article, Allen had already been seeing a therapist before the incident in the attic for his obsessive fixation on Dylan. After interviewing more than a dozen people, most of whom were closely associated with the Allen-Farrow family, journalist Maureen Orth reported scores of disturbing incidents in her story — Woody would have Dylan suck his thumb; Woody would climb into bed with Dylan and wrap his mostly naked body (save for underwear) around hers; Woody was once discovered by a babysitter in the TV room with his face in Dylan’s lap; Woody once applied suntan lotion to Dylan’s naked body and lingered on the crack between her buttocks, until he was admonished by Mia’s mother, the actress Maureen O’Sullivan.

You could argue that the crime that Allen is accused of — violating his own child — is even worse than the numerous improprieties committed by Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Kevin Spacey, and Louis C.K. But in Allen’s case, there’s only one accuser — which should be enough, but it’s the sheer of volume of accusations against other famous Hollywood abusers that has kept these stories in the news for the past few months. Sadly, that Allen is “only” accused by one person of the worst crime there is apparently has not been good enough before now.

When I started researching the history of Dylan Farrow’s accusations against Woody Allen, it was my intention to write about how my own love of Woody Allen’s films suffered as it became impossible to compartmentalize Dylan’s story. Like countless other men born in the ’70s and ’80s, the period when Allen was at his artistic and cultural peak, I willed myself into becoming a Woody Allen fan. For years I closely studying masterworks like Love & Death, Annie Hall, and Hannah And Her Sisters because I knew that being conversant with Woody Allen’s oeuvre was an essential part of being viewed as a “serious” cinephile, which I’m embarrassed to say was extremely important to me as a young man.

Looking back, it bothers me tremendously that my Woody Allen education occurred almost entirely in the shadow of the Dylan Farrow accusations. As I was accumulating an impressive collection of Woody Allen DVDs during my teens and 20s, I was also dimly aware that this man had been accused by a second-grader of sexual assault. For years, I didn’t know the full extent of Dylan’s story, but that’s hardly an excuse. The information was there, and it wasn’t even hard to find — the only inconvenience was to my own fandom. Why ruin Sleeper with some ugly realities?

“Can the art be separated from the artist?” is a difficult, thorny question that critics have been asking for decades, if not centuries. It’s a worthwhile conversation that at some point must continue. But, for now, let’s just push pause. Frankly, the impact Woody Allen’s (alleged) disgusting behavior might have on my and your enjoyment of The Purple Rose Of Cairo seems pretty trivial. Meanwhile, the more I read about Dylan Farrow, the more I notice how differently the media has treated Woody Allen, a man accused of assault, and Mia Farrow, the parent who raised and has steadfastly stood by Dylan, since the early ’90s. And it’s pretty infuriating.

If you want to know how in the world Woody Allen was allowed to have a thriving film career after he was accused of molesting his daughter, a good place to start is the 60 Minutes story from 1992, in which Steve Kroft interviews Allen shortly after Orth’s Vanity Fair story was published. The premise of the piece, I guess, is that Vanity Fair gave Dylan and Mia Farrow a platform, so it’s only fair that Woody Allen also has a platform. Which is fine, except the 60 Minutes pieces subs out journalism for unfiltered P.R. on Allen’s behalf.

Allen’s overriding point, which is not-so-subtly supported by the tenor of Kroft’s questions, is that Mia Farrow is a total nut job who has brainwashed Dylan and cruelly turned her against poor Woody because she was upset about his creepy romance with Mia’s adopted 21-year-old daughter, Soon-Yi Previn. Allen vents about Mia’s “crazy behavior, terrible rage, [and] death threats,” and shares a Valentine’s Day card given to Woody by Mia after she discovered his dalliance with Soon-Yi, in which needles have been carefully placed by the hearts of all the family members that Allen has disappointed.

Allen is never pressed about the most disquieting details of the Vanity Fair story — that there was an unwritten rule in the house that he never be left alone with Dylan, that he made her suck his thumb and sit by idly watching television as he put his head between her thighs, and that he touched Dylan inappropriately while applying suntan lotion in full view of other family members. The focus of Kroft’s inquiry instead is on Allen’s relationship with Soon-Yi, which was scandalous and weird but not illegal and not nearly as stomach-turning as his alleged violations of Dylan.

The slant of the 60 Minutes piece — Dylan’s accusations are an unfortunate byproduct of Woody and Mia’s bitter breakup — has more or less informed the coverage of Dylan Farrow’s story ever since. The actual substance of the allegations have been mostly buried. A 1992 interview with Time is similarly preoccupied with Soon-Yi at the expense of Dylan; it’s odd that a 56-year-old man having sex with his long-time partner’s daughter was somehow considered relatively acceptable, but the Soon-Yi story gave Allen a measure of cover for Dylan Farrow, with scores of journalists and reporters all too willing to accept the misogynistic “scorned woman” narrative explaining away the child-molestation charges.

Allen does not come off well in the Time interview, to put it lightly. He justifies his relationship with Soon-Yi, in part, by saying he never cared for the sizable clan of disadvantaged children that Farrow had adopted. His cold indifference is astonishing. “The last thing I was interested in was the whole parcel of Mia’s children,” he says. “I was only interested in my own kids.” (This has been contested by Farrow’s children, who talk about Allen being a father figure in this 2013 story.)

Later, when asked about the dubious contention that he “didn’t find any moral dilemmas whatsoever” in dating Soon-Yi, Allen simply shrugged. “The heart wants what it wants. There’s no logic to those things.”

In 1993, a Connecticut state prosecutor declined to pursue a case against Allen, in spite of his belief that there was probable cause, based on the belief that Dylan Farrow wouldn’t be able to testify against him in court. For 21 years, Dylan Farrow was relegated to an ugly footnote in Woody Allen’s triumphant movie career, until Dylan Farrow herself publicly accused Woody Allen of molestation in the New York Times in 2014. But Farrow didn’t stop there — she also implicated the media and Allen’s own fans for enabling him.

What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie? Before you answer, you should know: when I was seven years old, Woody Allen took me by the hand and led me into a dim, closet-like attic on the second floor of our house. He told me to lay on my stomach and play with my brother’s electric train set. Then he sexually assaulted me. He talked to me while he did it, whispering that I was a good girl, that this was our secret, promising that we’d go to Paris and I’d be a star in his movies. I remember staring at that toy train, focusing on it as it traveled in its circle around the attic. To this day, I find it difficult to look at toy trains.

A few days before Farrow’s editorial appeared, The Daily Beast posted a truly despicable fanboy apologia by Robert B. Weide, an Allen acquaintance who directed the fawning Woody Allen: A Documentary, which aired on PBS in 2012 as part of the network’s American Masters series. Not only does Weide reiterate the “Mia is crazy” narrative, he even impugns her sexual history, reminding readers of the times she hooked up with much older men when she was in her teens and 20s. What exactly any of this has to do with Dylan Farrow is unclear.

When Weide read Dylan’s piece in the New York Times, he stood by his hero, writing that there was “nothing that contradicts what I wrote.” He then added, seemingly unaware of his own smugness, “I hope she finds closure, and I sincerely wish her all the happiness and peace she’s been looking for.” For years, people like Weide have treated Dylan Farrow like a silly little girl who should stop imagining things and “find closure” by accepting that nothing happened to her after all.

Believing Woody Allen is innocent also requires believing his daughter is either a con woman, in cahoots with her evil mother, playing an incredibly long game, or deluded to the point of being utterly disconnected from reality. I’m sorry, but Annie Hall is not worth the price of buying that line of bull.