GRAND EXUMA, BAHAMAS — Great white sharks don’t stop growing. They never stop moving forward. Now well into his 60s and playing less golf than ever, PGA Tour veteran Greg Norman still proves worthy of his “Great White Shark” nickname. His evolution from can’t miss golf prospect to business mogul has made his second act as impressive as the first. And as his Shark brand grows from a simple logo to an empire that caters to wide corners of his sport’s lucrative markets, his success begs an important question: Can his blueprint translate from golf’s deep pocketed spenders to America’s other sports?

Norman, once an inseparable part of golf’s major tournaments, is the face of a conglomerate that handles everything from designing courses to selling high-end beef. His Greg Norman Company, the business behind the Shark brand, is a masterclass in reinvention. The aggressive style that earned him his apex predator nickname — and led to tremendous swings on the course and on the leaderboard — became his economic strategy. His brand once sequestered in hats and collared shirts now extends to the corners a niche catering to big spenders.

It’s a strategy built as a hungry 20 year old and held aloft as a banner for sexagenarian who neither looks nor acts his age. Norman’s public profile is that of a fun-loving retiree, but the image of a successful man whose private jet-riding, open-sea diving, wheeling-dealing attitude blends the non-destructive parts of Ric Flair and his own 1980s persona is no coincidence. Greg Norman isn’t selling clothes, or 18 holes of championship golf course design, or trendy Australian wines.

He’s selling shares in Greg Norman: the Shark, and it’s working. So how did Greg Norman transition from top-ranked golfer to lifestyle brand?

Norman was always a larger-than-life presence on the course, the aggressive young prospect who took the baton from superstars like Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer and ran with the weight of a nation on his back. The 6-foot-1 Australian would launch booming drives before riding his in-control short game to 88 PGA Tour victories, two British Open Claret Jugs, and one Masters’ collapse that earned him just as much notoriety as anything.

As thrilling as he was to watch, his full-throttle demeanor was what made him a star. Behind the drives were stories of outdoorsman adventure, like how his “Great White Shark” nickname, later shortened to the less clunky “Shark,” wasn’t just because of his never-stop attitude. Norman famously used to shoot great whites from the deck of his fishing boat back on the Aussie coast.

It also presented a unique opportunity, especially for a golfer. Norman’s professional career as a tournament player began in 1976, but it took 16 years — two of those as a PGA Tour money leader and more than three as the world’s No. 1 ranked golfer — before he’d built the cache to be more than an athlete. He was in his mid-30s when he bet on himself as the game’s next icon.

“It was probably ‘92, ‘93, when I knew my management contract with IMG was coming to an end,” Norman tells me over bottled water, sitting adjacent to a stack of Sandals Resort swag he’ll spend the next hour signing during a rainy day in the Bahamas. “I knew at that time, because of my status in world golf and observations I’d made with my management, I knew they were never going to build equity in my brand. You have a finite period when you’re going to be the No. 1 player in the world or a certain type of celebrity.

“They’re gonna maximize that, because they’re playing on commission. I started asking questions like ‘Where are my residuals,’ ‘Do I get a share of the TV take, of the gate money?’”

Those appearance fees were the first step on his quest toward building the Shark brand. Norman’s career success established him as the kind of player who could make or break a tournament. He used that leverage and a badass nickname to launch himself as a businessman. His break allowed him to partner with Reebok to create the Shark clothing line. That logo — a multi-colored Great White — and its presence in department stores across the globe was enough to push the PGA star beyond the golf-centric circles from which prior stars like Nicklaus and Palmer were aging out.

“My brand, my logo was recognized as a lifestyle logo,” Norman says. “That’s due to Reebok taking it in a different direction. It started to branch out quickly and at an early age. And then my lifestyle, people kind of live vicariously through me because I do so many interesting things. I recognized everything about my brand was pretty much golf related. But that pyramid can only grow so high. I realized then, as I was branching out, golf course design became a very valuable economic indicator.”

The Greg Norman Company’s portfolio looks like a shotgun blast from 10,000 feet, but a step closer to the canvas shows the established bridges between every unique element of his company. It starts with course design, but the resorts that brought him in need more than that. His interior design wing puts together the clubhouse. His apparel fills it. Norman’s wine and beef concerns supply the on-site steakhouse. It’s a wide net, but it’s fishing a very specific part of the ocean. So far, it’s been fertile ground for the organization.

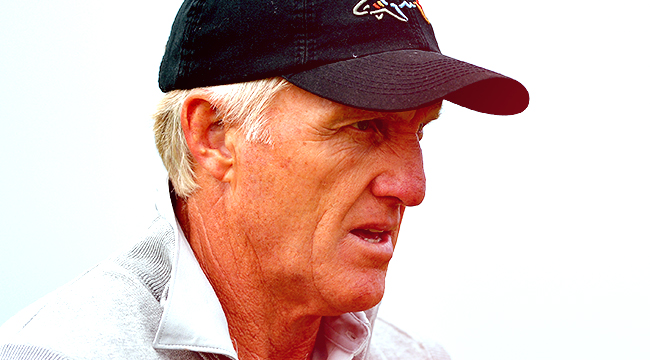

One day after our sit-down chat, we’re teeing off at a prime example of the Norman Co.’s vertical integration. Norman cuts an unmistakable figure at the course he designed at the Sandals Emerald Bay Resort. His innate likability, coupled with his stature as a titan of his sport, makes him a quiet giant during a 15-hole appearance at a Web.com Tour stop’s pro-am event.

Quietly confident and armed with a permanent sly grin, Norman stands tanned with perfect posture. Only his sun-worn skin betrays even two-thirds of his 63 years on the planet. At a pre-tournament reception, he comments on how technology has allowed him to hit the ball 20 yards further than he could in his 30s, but the fact he looks like he spends his afternoons deadlifting manatees at his Jupiter Island home may also play a role.

Today, he’s playing with a pair of journalists — myself included — and two weekend golfers from Texas who lucked their way into the draw. He never offers unsolicited advice for flawed swings or poke holes in approaches, but offers plenty of encouragement. He takes selfies and signs autographs for a small, but dedicated crowd that’s formed to watch the two-time British Open champion as he crushes his drives through the air.

He passes up a cooler of beer — ever on brand (and seemingly devoid of carbs) he sticks with wine these days — and offers it to the rest of the foursome. He offers a candid opinion on Tiger Woods’ comeback. He jokes with me about the sartorial decision to wear shorts branded with tiny moose emblems zig-zagging the legs. He is, after all, the Shark.

That’s when his success at a personal level becomes clear. You don’t just like Greg Norman, you want him to like you back.

It’s a track he applies his social media presence. Between Twitter and Instagram, he’s got more than 310,000 followers. He posts images from his day-to-day life throughout each week, showcasing the rich experiences of a life well lived. One day he’ll snap a picture from a boat, where he’s celebrating his latest birthday with the most fun inflatable slide you’ve ever seen. In another, he’s hanging out with Matthew McConaughey. There are pictures from his private plane, with his Shark logo perfectly featured on the winglet. It’s all part of the game, and even on vacation there are no days off.

“You’re always on the clock,” Norman opines with a chuckle. “When you’re the living brand, I think that’s the hardest thing for me to adjust and adapt to. No matter when you step out of your room or your house or your office or your plane, someone’s going to say or do something. If I’m not receptive, he might go ‘well screw this guy.’

“I’m that person anyways, but you always have to put yourself out there and be aware of what you’re saying, your reactions, how you carry yourself, even how you look when you get on an elevator. People stare at you, and if you stare back, well how will they interpret that?”

It’s a different attitude than the tenacious tack he’d developed on the PGA Tour. Instead, personality spills onto the layout he’s engineered at the Sandals Emerald Bay course, The resort, built on the tenets of sprawling beachfronts, swim-up bars, behind an all-inclusive emphasis on honeymooning couples, pushed golf to its forefront behind Norman’s cachet. He rewarded that faith by gobbling up some of the island’s most desirable real estate, a stretch of shoreline once occupied by the poured foundations of high cost condos.

He churned that land that into the course’s signature stretch, a gauntlet of oceanside vistas that swallow up any shot that hooks left. Over the span of six holes, the links turn the bay’s natural geography into one of the Caribbean’s most beautiful stretches of golf. This week, his association has helped the course land its own PGA event, the Web.com Grand Exuma Classic. The partnership, in this case, pays off for the resort, the tour, and Norman himself. Everyone seems to win.

Throughout his career, that personality — the ongoing persona that empowered him to strike out on his own — has created the opportunity he’s sought to extend his career and spotlight beyond a golf career that wound down in the 2000s. He’s optimistic his tremendous rise in the business world can be applicable to other athletes themselves, but one question looms: Can Norman’s blueprint translate from an upscale golf market to other sports that don’t cater to their own destination resorts?

It’s clear Norman’s intended customer base is a limited market that may not exist outside the upper class standbys who populate the world’s most expensive — and occasionally exclusionary — golf courses. When he addresses the game’s shrinking population, he makes it clear he’s not talking about the casual players who dial up discounted greens fees on GolfNow for a few humid weekends each summer. He’s looking at a wealthy group willing to drop five figures on the game each year.

When I press him on declining usage and membership rates at American courses, Norman is unconcerned.

“The golf cycle has flattened out,” he explains. “What happened with golf in the mid-80s and mid-90s was totally unsustainable. America was growing and building golf courses at the rate of 440 a year, year on year, for nearly 10 years. You can’t sustain that. Everyone just thought there was unlimited money because everyone was overleveraged.

“What we’re seeing today is completely different. Developers are a lot more sophisticated, money’s not as easy to come by. When you do your fiscal modeling, it’s a lot more of an intelligent process. It’s become incumbent on my generation of architects to be a lot more sophisticated in order to hit their return on investment or improve it.”

Sophisticated or not, there’s a big difference between a clientele able to spend upwards of five — and occasionally six — figures annually on membership dues and the average big three (football, baseball, basketball) fan in America. And while generational stars have been able to leverage partnerships with companies like Nike — think Michael Jordan or LeBron James — there aren’t many success stories when it comes to branching out like Norman has.

Curt Schilling’s attempt to turn his Boston area goodwill with a video game company bilked the state of Rhode Island out of $75 million in bonds, years of legal wrangling, and a shuttered studio. Dwyane Wade’s inability to commit to a budding restaurant business put him on the wrong side of a $25 million breach of contract suit. Archie Griffin’s failed shoe store franchise forced him into personal bankruptcy.

Were these failures the result of the personalities behind them? Or were they a case of stars roving too far from the arenas where they earned their greatest success?

“I believe every sport could take an internal look at themselves, from the NFL to Australian cricket,” Norman posits. “[But] there are certain sports where it would be difficult to monetize [the experience and vertical integration] of golf. It’s all about the ambiance, the setting, the destination that’s going to deliver an experience [visitors] can’t experience anywhere else. It’s a 52-week-a-year deal, which is also advantageous.”

And that’s the rub. Norman’s brand is a lifestyle, selling the one week per year for which you work the other 51. He sells the escape so well because the life he presents — the private jets, the oceanside views and white sand beaches, the exotic locales with a beautiful wife on his arm — is a full-time escape. His brand is all about living the dream, because for the past 40 years, Norman has been living the dream.

That works for him, but it’s a much tougher sell for athletes in sports that don’t carry that kind of fantasy appeal. Baseball can draw aging days to pre-Spring Training fantasy camps and Grapefruit League games, but outside the league schedule there’s no destination that can match with the kind of tourism golf generates. Basketball and football face similar problems. Norman was able to monetize the sport he knew, but finding an avenue to turn basketball into a brand without owing most of the credit to a shoe company is an entirely different beast for these other athletes.

It helps that Norman seems to have been born for the role.

“My nature, I can compartmentalize pretty easily, I’m a multitasker,” he explains, minutes before carefully signing that stack of Sandals hats with his name, the date, and a careful scribble of a golf green. “My saying is DIN-DIP — do it now, do it properly.”

Norman has been doing it properly for more than 40 years now, whether that’s been tearing up the PGA Tour, creating a business empire with tendrils in nearly every aspect of building a destination golf course, or just living the kind of life that makes others take notice. The Shark is still a man above all else, but his brand bled through his business and into his personal life long ago.

For someone like Greg Norman, that’s not a problem — but it’s not something other Hall of Fame athletes should expect to replicate, either.