Picture this: Stephen Curry is dribbling the ball on the perimeter. As the most dangerous shooter in NBA history, he is already in scoring position, because that’s just the way it is with him. But he’s about to become even more of a threat, because the Warriors are about to bring somebody up to set a screen on Curry’s man. All Curry needs is the tiniest sliver of space to let the ball fly and, in all likelihood, you’re going to give up three points.

The screener himself can present varying degrees of danger depending on whether it’s Kevin Durant, or Kevon Looney, or DeMarcus Cousins, or Alfonso McKinnie, but none of it changes the fact that giving Curry even an inch of room is poison to a defense’s ability to make a stop.

So, what is a defense to do? Let’s run through the unappealing options.

They can attempt to play things straight up, with the man guarding Curry fighting over top of the screen in order to stay attached. If he’s even a split-second behind on this attempt, though, it’s all over. Curry’s either walking into a three or getting to the rim. Curry’s man can try going under the screen to meet Curry as he comes around, but that would be incredibly unwise and would essentially amount to an open invitation for the best shooter ever to pull up from downtown.

The defense can blitz with both players in order to just get the ball out of Curry’s hands. Doing so invites a four-on-three opportunity once Curry makes the right pass, which he almost always does. If the screener is Draymond Green or Jordan Bell or someone like that, they’ll attack the paint and either finish at the rim or draw help and then spray the ball back to the perimeter for an open shot. If the screener is Durant or Cousins or even Klay Thompson, you’ve essentially given up a free basket. Plenty of teams have tried this before, and plenty of teams have failed.

The defense can switch the screen, but doing that just invites a defender who is entirely unequipped to defend Curry one-on-one to do exactly that. Have you ever seen a center get shaken into the ground before the best shooter in the history of basketball steps himself back into an uncontested three? It’s not fun for the team playing defense.

There are other options, to be sure, but these are the standard screen-and-roll coverages and if we’re being honest, they rarely work against the Warriors. Let’s say, however, one of them works — a team goes over the screen and there’s not enough space for Steph to shoot; or they go under the screen and somehow meet him at the exact point where he plans to pull, and he’s got no space; or they blitz and get the ball out of his hands and recover quickly enough to prevent a four-on-three opportunity; or they switch and their big man sticks with Curry on the perimeter. Let’s say whatever they try works and they get Curry to give the ball up to a man who is neither an immediate threat to score himself or in position to create an easy opportunity for somebody else.

Their job is done, right? The threat has been neutralized and they can relax and gear up for whatever comes next. At least, that’s what Curry and the Warriors hope they’ll think, because once Curry gives the ball up, he doesn’t just stop. He keeps going, relocating himself to somewhere along the three-point line so that he can stick a dagger into a defense’s heart.

Believe it or not, Curry is even more dangerous on the shots where he passes out and relocates himself behind the three-point line than he is when pulling up, stepping back, spotting up, or shaking a defender side-to-side before launching from deep.

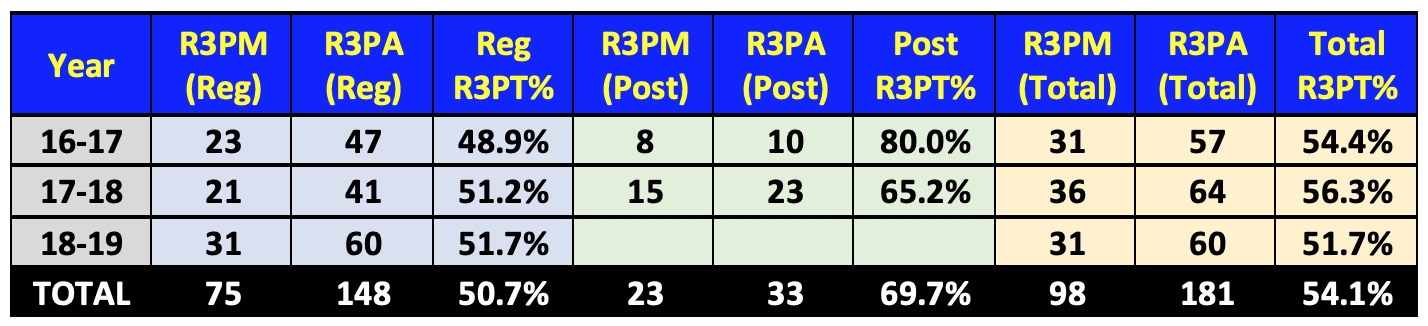

I watched video of all 2,155 shots Curry has taken from beyond the arc since the beginning of the 2016-17 season in order to track his percentages on relocation threes, and the findings were extraordinary. During that time, Curry has connected on a ridiculous 50.7 percent of relocation threes during the regular season, and even more ridiculous 69.7 percent during the postseason (albeit on only 33 attempts), giving him an absurd 54.1 percent overall.

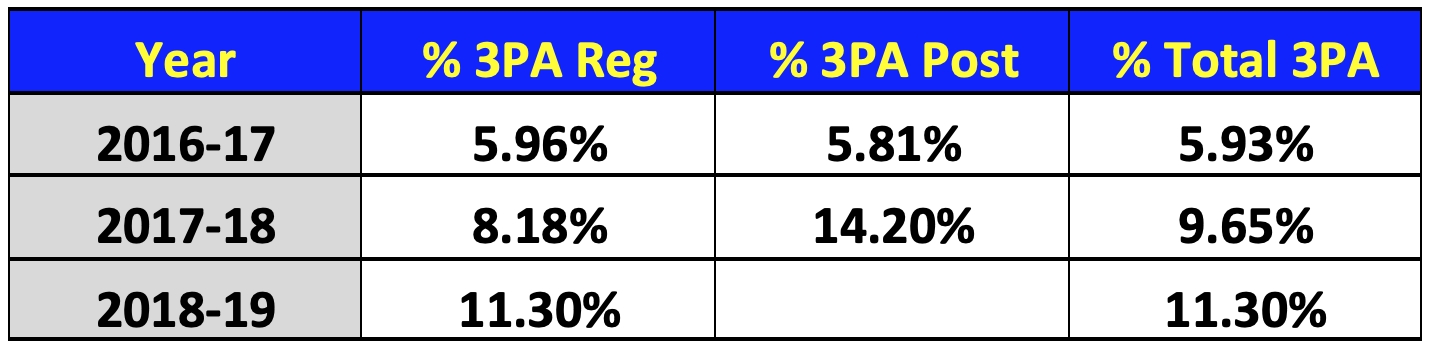

That means the average relocation three-point attempt by Curry has been worth nearly four-tenths of a point more per shot (1.62) than the average attempt by an NBA player inside the restricted area (1.24). The Warriors appear to have noticed the incredible value of these attempts, and their big men and wings are consistently on the lookout for Curry when he passes and relocates to another area of the floor. Relocation shots have made up an increasingly higher percentage of Curry’s threes during this time, to the point that they have accounted for more than 11 percent of his three-point attempts so far this season.

It’s easy to say that teams should just look out for this and prevent Curry from getting relocation attempts in the first place, but it’s far less simple than it sounds. First of all, Curry knows where he’s going and the defense does not, which gives him some breathing room in order to get open. Second, as seen in several of the clips above, he often uses the receiver of his initial passes as a screener to create even more separation for the relocation three.

A similar concept applies to defending the pass back to Curry as applies to his pick-and-rolls: If you devote extra defenders to stopping him, all it does is open things up for somebody else. Being a professional basketball player of Curry’s caliber usually means that you have mastered a few different skills on the basketball court. His ability to shoot and his ability to distribute have led to a Hall of Fame career, and when he’s able to use both of those in tandem on relocation threes, Curry is at his most dangerous.