Many artists live in fear of repeating themselves. However, some artists only repeat themselves, though they manage over time to do it in a way that always feels slightly different.

Granted, it often takes an audience member with infinite patience to notice. For instance, a layperson might argue that every AC/DC album is the same, and broadly speaking, they would be correct. AC/DC had a formula — gutbucket arena-rock riffs, salacious lyrics, adenoidal singing — that it reiterated time and again over the course of 16 studio albums. However, speaking as a person who has heard every single one of those albums, I would point out that any fan can discern the difference between Back in Black or The Razor’s Edge and Ballbreaker and Blow Up Your Video. The latter albums are examples of the formula being excellently executed, while the latter are examples of it falling flat. (This is to say nothing of the earlier Bon Scott-era records of the 1970s, which are obviously on another level.) Every album is the same, but the way they’re the same is always a little different.

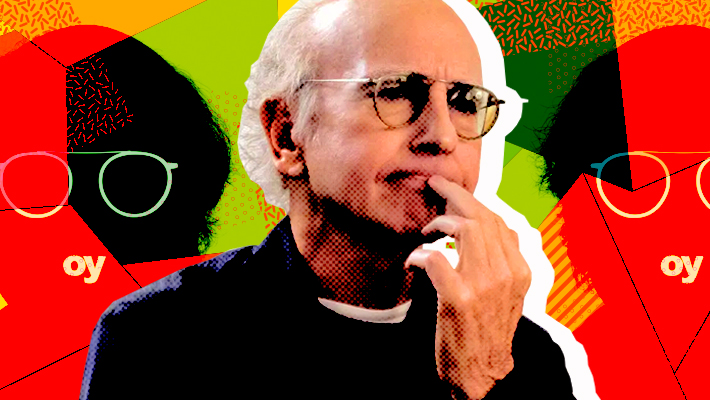

I bring this up in the context of the latest season of Curb Your Enthusiasm because Larry David is the AC/DC of sitcoms. He has a distinctive, brash style that he has refined over the course of 30 years as a major TV comedy auteur, first as one of the guiding forces behind Seinfeld, and then (since 2000) as the mastermind of Curb. His formula is as simple, direct, and (when executed to perfection) as satisfying as “Highway To Hell”: He’s the relatable a*shole, the everyman who is annoyed by all of the petty minutia that bugs all of us, only he isn’t afraid to give these grievances voice, even achieving a measure of vengeance on occasion. (“Dirty deeds done dirt cheap,” in other words.) He has applied this idea to all 10 seasons of Curb Your Enthusiasm spaced out over 20 years. But while each season seems the same, the way they’re the same, again, is always a little different.

Opinions will vary among fans over which episodes or seasons of Curb stand above the rest, but I think it’s fair to say that seasons eight (which aired in 2011) and nine (2017) were a lot closer to Ballbreaker than Back In Black. The 10th season, however, which began airing in January, has been pret-tay, pret-tay , pret-tay good. Actually, it’s been damn good. Shockingly good, even. To be honest, I didn’t think Larry and his zany band of cranks, misanthropes, and neurotics were still capable of wringing such consistent laughs out of those old, familiar riffs. But now that we’re more than halfway through this season, it’s safe to declare this is the best Curb Your Enthusiasm has been in more than a decade.

Explaining why this is the case is bit of a challenge, especially for those who might not like Curb or are only casual fans. On paper, the show isn’t any different. For instance, in the season premiere, Larry gets annoyed about the following injustices:

- People who say “Happy New Year” several weeks after the start of the new year.

- Too-soft scones.

- Too-cold coffee.

- A friend who keeps asking him to lunch. (He ultimately repels him by wearing a MAGA hat.)

- The prevalence of selfie sticks.

- The prevalence of motorized scooters.

- His inability to cleanly exit a party by using a “big goodbye,” i.e. a demonstrative farewell given to an acquaintance that you’ve been avoiding all night.

This is the sort of fodder that has powered pretty much every single episode of Curb. And yet the Season 10 premiere felt like an instant classic for the series — it was dense with premises while also feeling fleet and neatly plotted. Thankfully, it set the tone for a season that has hit with an impressively high batting average. The list of references and catchphrases from the first six episodes — “spite store,” “side-sitting,” “insufficient praise” — already puts it ahead of seasons eight and nine, which had stray standout episodes but were nevertheless mostly forgettable and irredeemably sour.

But, what exactly, has made Season 10 feel so satisfying? After all, Larry is still a jerk, he’s still making enemies left and right, and he remains hopelessly out-of-touch with the times. What makes this season the same but different in a positive sense?

I think it boils down to an important truism about the world of Larry David: Curb is the rare show that is better when the stakes are lower. The focus is back on the minor obsessions that unite us all — coffee that won’t stay hot, the luxury of handicapped parking, the embarrassment of a maid catching you in a compromised position with a sex doll. (Okay, maybe not that last one.)

The high-concept through-line of season nine — a fatwa is declared against Larry due to his involvement in a Salman Rushdie-inspired musical — extended from a poisoned worldview that took hold of Curb in the previous season, in which people are not merely irritating or needy, but angry, threatening and even dangerous. Some have attributed this to Larry’s divorce from Cheryl in season six, which is credible. (Though season seven, aka “the Seinfeld season,” remains a personal favorite.) In subsequent seasons, Curb was often shrill and mean-for-the-sake-of-being-mean, like season eight’s recurring “social assassin” bit culminating with a confrontation with Michael J. Fox, or the anti-P.C. jokes about “butch” lesbians from the season nine premiere. While the show was still funny at times, the sense of camaraderie and goodwill that Larry has with his extended circle of friends and compatriots seemed muted and overwhelmed by toxic misanthropy (as opposed to the relatable, “healthy” misanthropy we all experience in relatively small doses).

This is not to say that Curb has not taken any risks lately. In fact, one of the most impressive parts of this season is how often the hot-button jokes haven’t gone wrong, in spite of the obvious dangers. The ongoing #metoo-inspired storyline involving Larry’s assistant has come closest to short-circuiting, but the resolution involving an ongoing scones-related storyline made it ultimately seem like an absurdity than ax-grinding. (Also, playing on Jeff Garlin’s resemblance to Harvey Weinstein was truly genius.) Meanwhile this season, there has been a Nazi dog, a “yo-yo dieting” girlfriend, a pledge among friends to ditch whoever winds up getting cancer, a sociopathic (and Seinfeld-esque) mailman, and Vince Vaughn as Marty Funkhouser’s brother. All of these things, and more, could’ve felt like misfires. (Particularly Vaughn, who hasn’t been this funny and charming on-screen since the mid-aughts.) But Curb has hit the mark on all of it.

The secret of Curb‘s success is that Larry can only be an a*shole when he’s our a*shole, giving voice to the indignation we all feel over stupid things in the world that we’d feel stupid complaining about in polite company. Season 10 feels like a return to that. Larry might react to life’s indignities with hostility, but the show itself doesn’t feel hostile, especially compared with recent seasons. It feels more like venting with an old friend, again.