The playgrounds of New York City have produced some of the most legendary figures in basketball history. Venues like the Dyckman and Rucker Park occupy a singular place in streeball lore and represent the gauntlet that up-and-coming players have to navigate in order to prove that they can thrive in hostile and unforgiving environments.

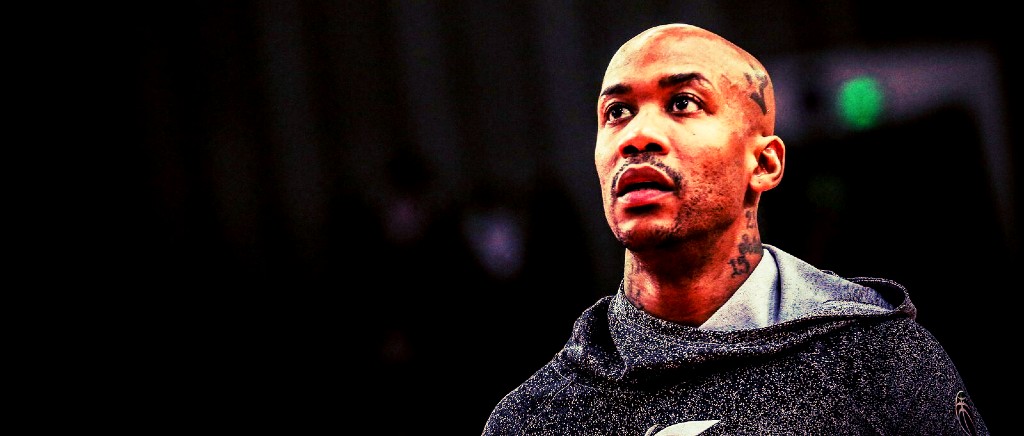

Stephon Marbury is just one example of a homegrown product who catapulted from the playground to international acclaim, but his basketball journey has been anything but ordinary. Rather, it’s been a circuitous path that began with NBA stardom and took a sharp detour that culminated in an almost mythological late-career renaissance in the Chinese Basketball Association.

Over the better part of a decade, Marbury won three championships with the Beijing Ducks, setting a new precedent for former NBA stars looking to extend their careers overseas, and in the process, became one of the country’s most beloved and celebrated athletes. He’s been immortalized in statues, and he’s had entire museums and theatrical productions dedicated in his honor.

A new documentary, A Kid From Coney Island, takes a more intimate look at his life and career, tracing his basketball lineage through his family members and examining the people, places, and situations that have defined and influenced him as a player and as a person.

We spoke to Marbury last week via telephone about the film, which hits theaters on March 10, and about his transition to coaching and much more.

Your career is one of the great, and I think, most unorthodox redemption stories we’ve seen in basketball. Why did you feel that now was the right time to tell that story in a documentary like this?

I mean, the timing was perfect because I’m retired, I’m onto the next chapter in my life and coaching. There was a lot of information that people were eager to receive, looking at my career over the last 22 years. It’s a story that people wanted to see, people wanted to know about all the different things that have taken place over the course of time. So I thought that this was the perfect opportunity to do that.

What was the collaboration like with the filmmakers [Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah]?

It was great. They both are two creative minds that share the same viewpoint in storytelling. And I think those guys, they fit for what it was that I was trying to get across in my message and trying to inspire and trying to get people excited about what went on in my career. I think both of them, they really hit home, and they both trust in God, which I do as well. So we both, all three of us, we share and we manifest on the same level. So I think working with these two guys, along with Nina Bongiovi and all of the people that have come on, Jason Samuels…Kevin Durant, all these different people coming together, they felt something that was pretty powerful in the story to get behind it.

One of the things that struck me the most was just how family-focused it was. We learn a lot about you from your family members, which was kind of the beating heart of the movie. Why was it important for you to put your family at the forefront of this story?

I mean, my family has been everything. All my brothers play basketball, my three older brothers. My older brother played against Mike [Jordan] in college, played with Dominique Wilkins. Another brother played at Texas A&M. He was the seventeenth leader in scoring in the nation at one time. Another brother was highly recruited that played at St. Francis College. And then myself. So this started way before me.

So having my family close, the stories about what went on during a time period in my life was important. It was something that I felt had to happen. And that’s not even the whole story. There’s still more. It’s a lot more. You can’t really compile 22 years into 90 minutes. But being able to give the gist of that time period of things that happened, events that took place, it’s kind of cool that they’re able to tell that. They were able to share stories about when I was younger. Those are the best people in the world to tell other people about how I felt, what I wanted. And my brothers and sisters, they’re truthful 100 percent. If something ain’t right, it ain’t right. It doesn’t matter if it’s me or not. Of course, they don’t want to hurt me, but at the same time, they’re going to tell their truth.

Speaking of that, the movie didn’t shy away from some of the more difficult parts of your career. Like your time with the Knicks, for instance. I thought Stephen A. [Smith] made an interesting point about how it would have been more beneficial to have someone on your side in the media to get your message across and tell your story during that time of your career. What did you think about that comment from him?

I mean, I feel like the best part about the documentary is you have people that share their viewpoints. Stephen A. said he only knew me from what he knew and what he read and what he heard. He knew me for a short period of time when he was on the come up. I knew Stephen A. Smith before he became Stephen A Smith. So for me, there is some stuff that he spoke and said in the past, which he was dead wrong about. The information was incorrect. But in general, the story is that story for that time. Some journeys are this way. But I think, overall, it hurt not having a point person who I could have used as an outlet to be able to spread what was the truth. Because at the end of the day, it’s your side, my side, and then the truth.

Right. So a lot of people don’t know what happened and why I did or why I said what I said. It’s just “oh, I said that, oh, I did this.” I mean, everything has a reaction and the action in it. So I think the documentary, it basically spills out a lot of things that are like those “oh, I was believing this for the last 20 years, and now I see like oh, now that makes sense.”

Absolutely.

Because you can’t be what they were trying to make me out to be and then go to a place where there’s almost a billion people and build two statues and a museum and all these different things. Like, this type of human being is not the redemption part, the basketball part is what it was. But all of the other things, I’m not perfect. I’m far from perfect. I’m so far from perfect. But I’m not as bad as I was being depicted to be.

Which I think, it’s cool, because that’s American media. When it’s the American media, it goes either way. Life is learning lessons, and without those life-learning lessons, I wouldn’t be able to be on the phone talking to you about what we’re speaking about.

I wanted to talk about China, of course, because like you said, all the championships, the museums, the statues, the theatrical productions, how surreal of an experience has this been for you?

I can’t really explain it, man. It’s like an out-of-body experience just showing the movie. It’s like you’re watching all that is happening as you actually work hard, and you’re living inside of it, and you’re focused, and you’re determined, and you’re dedicated. And all these different things that you need to do in order to try to reach and build success anywhere. And you’re doing your thing, but you’re also watching all of these accolades that are happening…So for me, all of these different experiences are all a part of the plan, obviously, but it’s a teacher. It’s a teacher for myself, it’s a teacher for myself to teach others. So it’s a great experience.

That teaching aspect of it has come more to the forefront since you’ve transitioned into coaching now. So what has that experience been like?

At first, I did not want to coach. I wanted to retire and take some time off. When I say I didn’t want to coach, I didn’t want to coach right away like how I did. But it’s funny, so my godfather — I call him my godfather in China, he’s like one of wealthiest people in Beijing, but just super humble — watched me play, went to the championship in 2012. He’s never really watched basketball. He’s like, this guy’s spirit is like he never gives up.

And our relationship grew after that, and he said to me after I retired, he said, “In Chinese culture, it’s kind of like if you don’t coach right after you finish playing, it’s like when people bring the food out and they sit it on the table.” He said, “After a while, nobody’s going to want it.” So I was sitting there listening and thinking about it. I was like yeah, I don’t want no cold food, do you know what I’m saying? So coaching wasn’t really part of what I wanted to do right away, I kind of had to do it, because I made a commitment and said that I wanted to do it.

But once I decided to do it, I fell in a whole different space of love for it, and teaching and seeing guys go from one space to another space and learning how to play the game, and letting guys have their freedom but also giving them a little bit to stay consistent, not change their game, but do this, and this right here will help you stay consistent in what you’re doing. And what I started to see, after pressuring and hard work and the results, that’s when I was like, wow, this is really cool coaching. You got your challenges, but at the same time, I love it. I can’t say enough about working with the kids. Some of these kids, I’m old enough to be their father. So it’s an experience.

In the NBA today, we see so many athletic, scoring point guards, do you ever wonder how your game would have translated today or do you feel like this would have been an era that — obviously I think you could have played any era — but do you think you would’ve been able to thrive more today?

Yeah, I’m one of those guards. I always see myself with the guards in that transition and people being able to accept a point guard scoring 36, and if he doesn’t score 30 points it’s like aw, man, he didn’t score that much. Before, it was like when we were doing that, it was like, aw, you’re not a point guard, you shouldn’t score. Like now, if you can’t score as a point guard, you can’t play.

When I look at the game now, we were the guards that helped transition the game, where it’s fun to see the little guard do all of the things that the little guard’s able to do on the court. So it’s cool. I like today’s game, how they’re playing. I think the kids are way more athletic than what we were. You see guys jumping from the free throw line now, throwing the ball between their legs. That’s like a regular dunk now. If you don’t throw the ball between your legs or throw it around your back, it’s not even a dunk anymore. It’s crazy, but it’s cool. I love it though. I’m like, wow, this is amazing. Look at that kid, just like what is he going to do on the break? So it’s cool.

One of my favorite All-Star Games, 2001, you hit those threes to steal the win for the East. That was when All-Star Games were still really competitive. What did you think about the new format of the All Star Game this year?

I mean, the format is the format. As long as they play hard, that’s the most important thing. That’s how I grew up, watching Magic, and I’d see them go at it, Jordan, Patrick Ewing, all of them dudes going at it. Those dudes, when they got on the court and played, when we watched that when we were younger, it was like man, I can’t wait for the All-Star Game, because you were going to see the East play against the West. I’d start watching games where guys are just letting guys go dunk. When I first seen it, I was like, hold up, did he just throw the ball to the other team so he can go and do a dunk? I was like, no, I’m not rolling with that. That’s not part of the game.

The way they played this year, I think, and I was saying it before the game, I was like this is going to be the best All-Star Game. And those guys came out and they played with Kobe’s mentality. Because that’s how he played.