On Monday night, HBO aired Brett Morgen’s incredibly powerful documentary Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck after a run in select theaters. The documentary — heavily made up of never-before-seen home videos, journal entries and drawings from Cobain himself — took an unusual approach to tell his story. Entire sequences scrolled through Cobain’s journal entries of scattered thoughts, letting his written words advance the narrative. Animated recreations took the place of where real footage would typically exist. And in a bold choice for a Cobain-centric film, Montage of Heck spends the least amount of time on arguably the two most infamous events in Cobain’s history, his overdose and subsequent coma in Rome and his death. Instead, the film spends a lot of time on Cobain’s psyche and how various events in his life put him in an emotional position where those tragedies could happen.

If you didn’t catch Montage of Heck in theaters or on HBO, well, you should. It immediately enters the canon of music documentaries. Until then, here are six clips from the film that you have to see:

“What else could I be? All apologies…”

[protected-iframe id=”08acfe5ee53164446ea3dcfe62c25602-60970621-85082642″ info=”” width=”640″ height=”354″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

It didn’t take me long to get chills. This sequence is very early in the film, and typical of many documentaries, it’s just childhood footage of Kurt set to a gentle, music box version of “All Apologies.” But the score is beautiful, and as you watch Cobain do things normal, happy children do while listening to his mother describe how magnetic he was, you can’t help but juxtapose it with who he later becomes. And though the music strips the song’s vocals, the mind instantly fills in those blanks with the quote above. It’s heartbreaking, like little Kurt knows the good times can’t possibly last, and he’s already sorry for how he eventually winds up. What else could he be, other than Kurt Cobain, the tragic hero, when his childhood turns into…

“I don’t know how anybody deals with having your whole family reject you.”

[protected-iframe id=”f83e88ccbf648c4fe0354a164d5234bd-60970621-85082642″ info=”” width=”640″ height=”354″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

“Rejection” is a theme that blankets Montage of Heck. Kurt was apparently hyper-sensitive to it, which would inform his less-than-ideal relationship with the press. Krist Novoselic later says in the documentary, “He hated being humiliated. If he ever thought he was humiliated, then you’d see the rage come out.” We see where the seeds of that insecurity are planted, as his stepmother describes the impact his parent’s divorce had on him. As his behavior worsened, he was kicked out of his mom’s house, and then his dad’s house, and subsequently spent a lot of time living with, and being kicked out by, various relatives. Nobody could stand to live with teenage Cobain for more than two weeks at a time, according to his stepmom. “He just wanted to be the most loved,” she says. But that rejection led to a cycle of bad behavior and more rejection.

“I love playing music, but something’s not right, so I decided to medicate myself.”

[protected-iframe id=”c99d1d6ad6bcbdd79376e04c4e6375a8-60970621-85082642″ info=”” width=”640″ height=”354″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

Cobain’s history with stomach problems, and how it started his heroin use, is a fairly under-documented facet of the singer’s story, despite its large role in his eventual undoing. But we get more insight into it here, learning via a journal entry that Cobain first took heroin in 1987 to ease the pain, and he used it about 10 times in a three-year span. Though it’s not mentioned in the documentary, the eventual healing of his stomach pains later in his life actually led Cobain to temporarily go clean, but by then he was already in too deep for a permanent turnaround.

“You are not ready for this.”

[protected-iframe id=”deb4fd65144e4916cffd2db05b9dd0e0-60970621-85082642″ info=”” width=”640″ height=”354″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

Wendy O’Connor, Kurt’s mother, describes her first time hearing Nirvana’s breakthrough Nevermind. She recognized immediately what it meant for the band, and Cobain’s life, and knew her son wasn’t equipped to handle what fame brings with it.

“She was interesting, she was artistic, intellectual… and she did drugs.”

[protected-iframe id=”04c32b2ff27e5ca0af476b3f8b7e0c99-60970621-85082642″ info=”” width=”640″ height=”354″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

Sadly, Cobain’s mother was right. In this clip, you see journal entries outlining Cobain’s struggles with fame, and Novoselic goes on to describe how Cobain used heroin as an escape. It was at this fragile, tumultuous stage that Kurt met Courtney Love. “He wanted to build a home because his home and his family fell apart,” Novoselic says of what drew him to Love in some of his darkest hours.

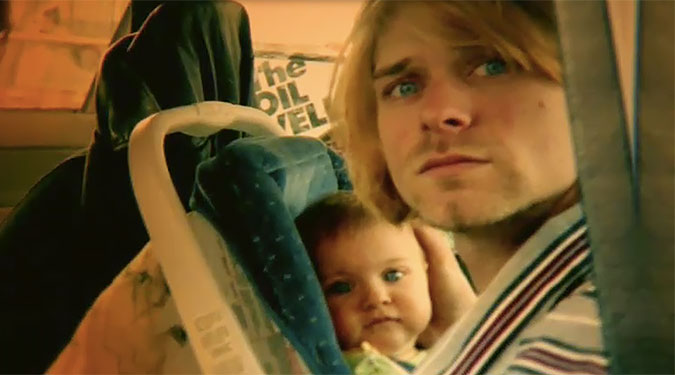

“I don’t want her to be screwed up.”

[protected-iframe id=”93252ef787ad6c452eac06cf15ad3bb6-60970621-85082642″ info=”” width=”640″ height=”354″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

I came away from Montage of Heck very conflicted regarding how I felt about Kurt, the father. In this clip, he tells an interviewer how much his daughter Frances Bean means to him, saying he’d give up his career if it meant saving her psyche. There are clips that show Kurt to be a genuinely loving father, and what he’s saying in this clip is sincere. Then, you hear about how Love continued to do heroin while pregnant with Frances Bean (and see Love in the modern day almost flippantly brushing it off as nothing because she is always the worst), and you later see a clip of the two giving Frances a haircut in which both are constantly nodding off, obviously very high, and you — the viewer — feel rage.