The mayor of Marion, Ind., M. Jack Edwards, was fast asleep when he got an unexpected visit from a 6’10 black man and his teammates in the middle of the night. The 6’10 black man and his teammates were not happy.

Bill Russell and his world champion Boston Celtics had just been awarded the key to the city of Marion earlier that day in a ceremony that was cordial and celebratory of the team’s success. However later that evening, Russell and his teammates Sam Jones, K.C. Jones and Carl Braun went to a greasy spoon hamburger spot after their exhibition game in Marion. They were refused service at the restaurant.

“The place sat about 40, but there were 10 people inside,” Braun recalled in the book Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA. “The hostess looked at us and said, ‘All the tables are reserved.’ All the bar stools were empty, so we started walking in that direction. Then she said, ‘sorry, those are reserved, too.’”

“We got the message and left.”

Russell and some of his teammates were so outraged that they took to the Mayor’s office to give him his key back. They weren’t standing for discrimination or any city that allows it to happen. So Russell proceeded to wake the mayor to let him know that he can take his key to the city back.

“Russell accepted that role in that situation to lead,” Celtic teammate Satch Sanders tells DIME. “We followed his leadership. He set the example and we were right there with him.”

And oftentimes where Russell would lead his team — besides to 11 championships, of course — was towards facing social injustices that were all too common in the 50s and 60s.

“I never thought segregation was okay,” Russell said in an interview with the NBA. “You hear people say, ‘that’s the way it was at that time.’ I never cared what the time is. It’s never alright.”

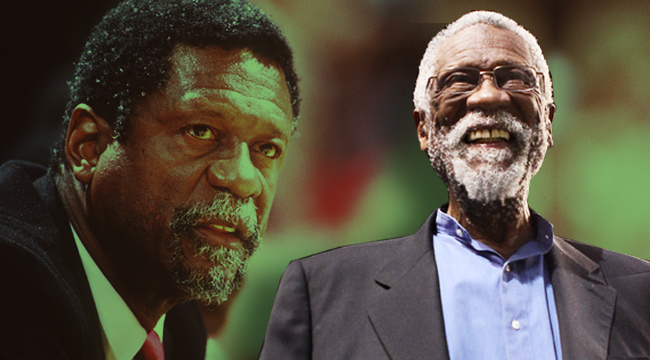

Bill Russell’s on-the-court record is unimpeachable: 11-time NBA champion taking different incarnations of Celtics teams to glory along the way. But sports dominance was to be expected. He was almost seven feet tall, and he towered over his competition. And as is often the case, hyper-athleticism from black athletes is an acceptable method of excellence.

While his status as a celebrity was challenged in the more racially segregated 50s and 60s, he really broke barriers when he became a player-coach in 1966 and the first black coach in the NBA, and in all of the major sports.

As much as Russell was revered as a player, he faced countless instances of racism. At one point, someone broke into his house with the sole purpose of defecating on his bed. This all prompted Russell to call Boston a “flea market of racism.” Still, Russell had earned a level of respect in Boston for his role as a player who brought rings to the city. However, the idea of him being a coach brought about plenty of skeptics.

One reporter in the press conference announcing the coaching decision asked if Russell would be able to coach without discriminating against the white players (as if anyone ever bothers to ask white coaches if they will avoid discriminating against black players).

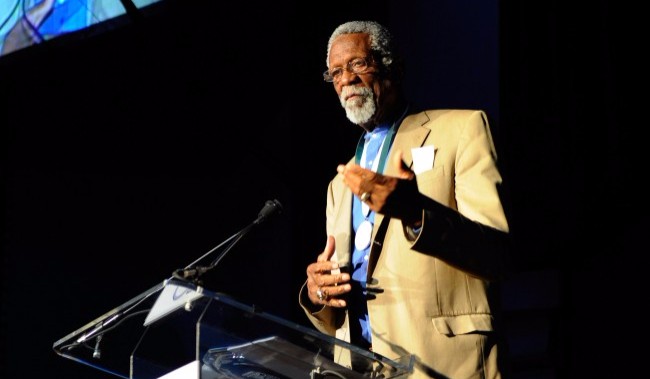

Russell acknowledged the importance of his role as a pioneer, but he’s always been adamant that he took the job because he thought he could succeed.

“If Red [Auerbach] had ever said to me, ‘this is a great social experiment,’ I would have nothing to do with it,” Russell said at a 2014 panel at the University of Texas. “The only reason I would do it is if I’m convinced that I’m the best person to do the job.”

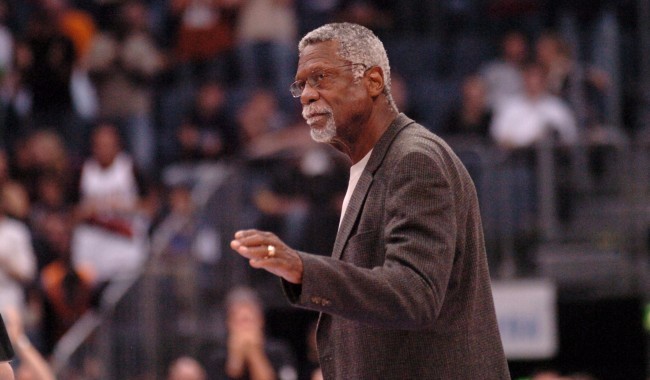

Russell proved himself to be a more than capable coach, leading the Celtics to consecutive NBA championships in 1968 and 69 with no assistant coaches helping him out. All the while maintaining MVP-level play.

“Bill was a good coach,” Sanders remembers. “But we really still needed him out there playing. As good as he was, we still needed him to be dominant on the court.”

While being a coach, Russell maintained his fervent defense of civil rights. For instance, in 1967, Russell joined a contingent of athletes including Lew Alcindor and Jim Brown to determine Muhammad Ali’s convictions about not participating in the Vietnam War and eventually stand with him in his protest. The player summit became a landmark moment in black athlete activism in a time when the country needed it the most.

By the time Bill Russell retired as a player and coach, he’d led Boston to a total of 11 titles and earned himself five MVPs. His legacy as a player made him one of the all-time greats. But his legacy as a coach paved the way for other African-Americans to find their places on the sidelines. Not only did teammate K.C. Jones go on to be a coach, countless black coaches credit Russell with inspiring them to coach.

While Russell’s coaching stint with the Celtics is his most successful and definitive, it’s also pretty easy to pinpoint his play as a major contributor to his team’s success. But what’s underrated about Russell’s ability as a coach is his run with the Seattle Supersonics from 1973 to 1979, taking the struggling expansion team to a winning record, and helping build a team that would make the NBA Finals in the two years after he left.

Russell is a basketball genius. And his coaching job with that Sonics team deserves more praise in highlighting that fact.

Every black basketball player owes a debt to Bill Russell and the other players from his generation who paved the way for them to find success. Russell’s work as an activist, coach, and floor general were unprecedented. Without his tireless and often thankless efforts, there’d be no Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul, Dwyane Wade, and LeBron James in suits speaking up at the ESPYs.

There can be plenty of arguments about who the greatest player ever was, but if we’re going to combine on-the-court success with real-life activism and being an agent of change, then it’s hard to find a peer for Russell.

It’s all because he lived by a simple mantra passed down from his mother:

“My mother would say, ‘always stand up for yourself,’” Russell once said. “So if someone did something I didn’t particularly care for, I made sure they knew it.”

And he did so whether he was taking on racial injustices, doubts about his ability to lead, or an unsuspecting mayor of a small town in Indiana.