He knows it’s coming. He’s heard it, he’s grown up in it, and he’s made do with it. Shareef O’Neal swerved from the path that would have forced him to try to play out of position, and instead established his own brand of dominance on the court.

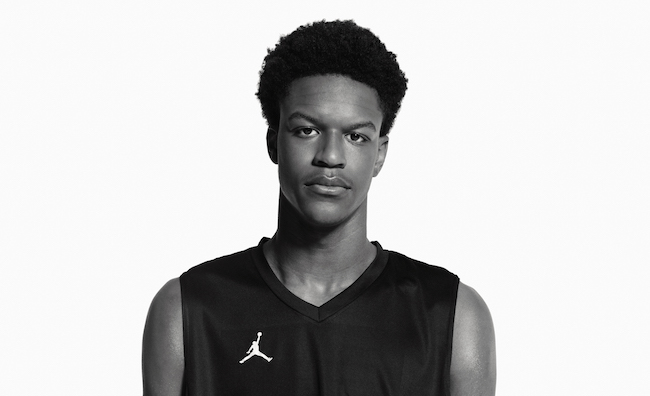

Your first impression of Shareef is that he resembles Paul George or Kevin Durant more so than the most dominant post player ever, his father, Shaquille O’Neal. Yes, the height gene was passed down from his pops, but he lacks the bulk that made his father such a force — Reef checks in at 6’10, but weighs only 220 pounds.

“When my dad first started training me, he never trained me like him,” the younger O’Neal tells Dime. “He made me watch hours and hours of Kobe, Tracy McGrady, LeBron and players that were taller but played like guards. He never taught a post move until I told him I wanted to learn a post move.”

As a slender 6’4 freshman, Reef showed flashes of the dynamic wing player he would become, but his coaches saw a big man in the making. Finding his way Windward High in Los Angeles, O’Neal had a tough time fitting in.

“All the coaches I had were like, ‘Your dad’s a center, you’re probably going to be as big as him, let’s put you in the post,’” O’Neal says. “Every time I’d shoot an outside shot, they’d be like, ‘Nah you gotta stay in the post.’”

Still, when you have a dad in the Hall of Fame and a pro-sized body, you’re going to get looks. O’Neal improved his production as a sophomore and the college looks came. Things weren’t so smooth, though, and he would look to transfer.

“The next season I actually had a big problem,” O’Neal says as he looks back on his sophomore season. “One of our coaches got a job in the WNBA, and we got a new coach, and he didn’t let me shoot outside at all. And that didn’t end well.”

So off he went to nearby Crossroads School in Santa Monica. Despite boasting eventual Arizona commit Ira Lee, the team had an up and down season, bowing out in the quarterfinals of the state championships. It was equal parts transitional and a leap for Reef, and when he got the chance to show what he could do, he thrived: O’Neal showed out against the nation’s top prospects, going for 17 points against a Marvin Bagley-led Sierra Canyon team and 20 in a matchup against Bol Bol and Mater Dei.

In his senior season, it was his team to lead. The season before gave Crossroads exposure, but this put O’Neal and his squad in the national spotlight. With a loaded schedule crisscrossing the country against the nation’s top teams, with packed gyms full of pro players and influencers meeting them at each turn, every game was an streamed and covered with a new age buzz.

“I think it’s a challenge and it helps us at the same time,” O’Neal says. “We all like getting exposure to able to people show what we can do, but since we’re the underdog in this situation it’s also a challenge.”

With all eyes on Shareef, he led Crossroads to a state championship, finishing with a 25-9 record and an unblemished mark on their home floor. The attention and pressure locked him in, something that may have been lacking. It proved to be the edge he needed for O’Neal to embrace the leadership role he had been pegged for.

“My mindset has changed a lot,” O’Neal points out. “At the beginning of the year, I didn’t have the same mindset. I feel like I was too nice on the court.”

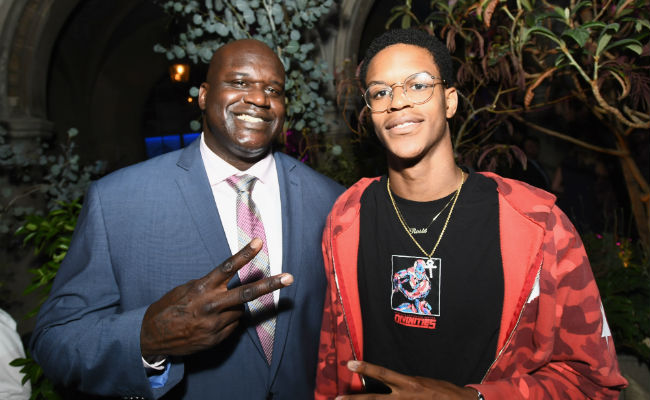

One would think when basketball success is in the family, it’s a regular topic around the dinner table, with children receive next-level tutelage from pro level coaches and everyday lessons in hardwood wisdom. You also carry a burden with a name on your back, getting everyone’s best shot, no matter a championship game or summer pick up.

“A lot of people think I got all of this exposure just because of what my name is, and I don’t know what’s real and what’s not,” O’Neal says. “I feel like a lot of NBA players’ kids have proven they can play.”

NBA rosters are loaded with the offspring of guys who played in the league. Run down the list — Dell Curry, Tim Hardaway, Glenn Robinson, Larry Nance, Harvey Grant, Glen Rice, Doc Rivers, and Mychal Thompson all have sons who play professionally. Looking to high school, there are more coming. Scottie Pippen, Kenyon Martin, Manute Bol, Dwyane Wade, and LeBron James all have sons that are promising young players.

The pro parent formula makes plenty sense. It starts with elite level athlete genes, along with a childhood exposed to the game at its highest level from birth. There’s something about following in your father’s footsteps and considering a life in what you know. Taking up the family business. However, the burden weighs heavy, one where you must always prove yourself. Something O’Neal has shown he can handle.

“If you’re an NBA player’s son, and your dad is one of the best to ever play the game, you’re going to have a big target on your back,” O’Neal admits. “So like Bol Bol, or LeBron’s kids, they’ve probably got an even bigger target on their back. You’ve just got to work harder to make people know that you’re not just playing because of the name on our back. You can actually play the game.”

As for next year, Shareef initially signed with Arizona, but in the wake of a corruption scandal surrounding the program, he decommitted and opted for UCLA. A move to a school with a rich history and track record of turning out solid pro players, O’Neal is ready for the push, one that he knows will come with a new wave of comparisons.

“Going on to next year, it’s probably going to be one of my biggest years in my basketball career, the most pressure,” O’Neal says. “Being a freshman in college and because of what my dad did in college. People are going to compare that to what I do next year. It’s a lot of pressure, but I just can’t worry about that. It’s something I’ve got to look over. It’s always going to be there.”

High school served O’Neal well, where he proved he could take center stage against the nation’s top competition. He came out a winner, establishing his own identity, filling some of basketball’s all-time biggest shoes.

Looking ahead, Shareef has addressed his approach and how to keep coming through when challenged.

“I think I just have to keep a positive mindset on and off the court,” O’Neal concludes. “I can’t doubt myself. I know I’ve doubted myself early in my high school career and that kind of messed me up. I’ve chosen to play basketball and I knew it was coming. It’s here and I’ve got to fight through it.”