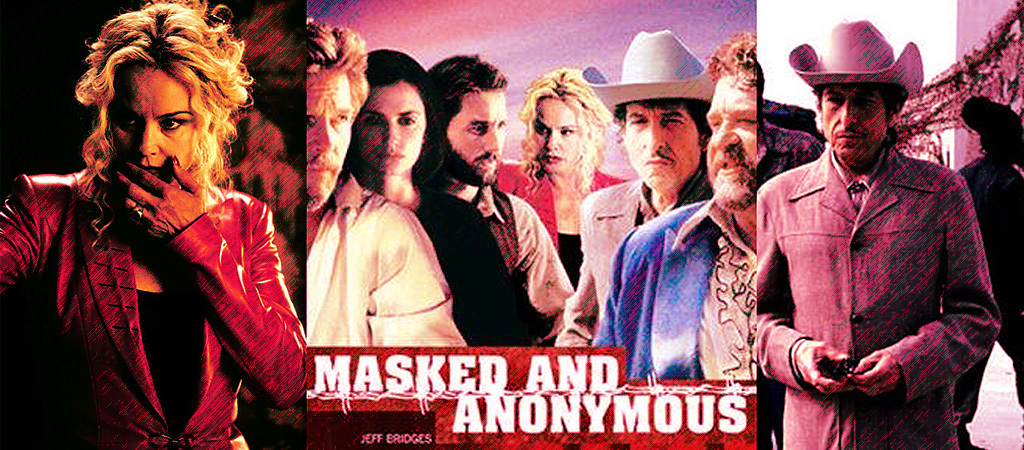

Twenty years ago this month, one of the weirdest films ever to be distributed by a major studio in the 21st century came out. Released in a small handful of theaters the same weekend as Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over and Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle Of Life, the movie marked the directorial debut of Larry Charles, the behind-the-scenes right-hand man for Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David during the ’90s on Seinfeld who later achieved cinematic notoriety for his collaborations with Sacha Baron Cohen on the films Borat, Brüno, and The Dictator. For his first movie, Charles corralled an all-star cast headed up by John Goodman and Jeff Bridges — their first onscreen pairing since The Big Lebowski five years prior — that also included Luke Wilson, Jessica Lange, Penelope Cruz, Angela Bassett, Val Kilmer, Mickey Rourke, Ed Harris, Bruce Dern, Christian Slater, Chris Penn, and Giovanni Ribisi.

And then there was the film’s mercurial leading man: Bob Dylan, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Charles under the pseudonyms Sergei Petrov (Dylan) and Rene Fontaine (Charles). In Masked And Anonymous, Dylan plays Jack Fate, a washed-up rocker who has been recently let out of prison so that he can perform at a benefit concert. Why was he in prison? Well, his father is the strongman-style dictator who runs what appears to be a post-apocalyptic version of America. And father and son were involved long ago with the same woman. And that’s (possibly?) why he was jailed. Also: Jack Fate is in his early 60s, and his father appears to be around the same age. And he dresses like a cowboy from a 1930s western, even though the film (possibly??) takes place in the future or at least an alternative present circa 2003.

Not much about Masked And Anonymous makes literal sense. It follows the rules of songwriting, not cinema, where surreal and nonlinear storytelling is more common, particularly in Bob Dylan songs. But mainly it’s just straight-up bonkers, following a loose narrative thread that functions primarily as a vehicle for a lot of colorful actors to give scenery-chewing performances. It’s the kind of movie where Val Kilmer shows up as a character known only as Animal Wrangler, and rambles in Bob Dylan’s general direction for several minutes about how people are worth no more than a crack in the mud at the bottom of a sun-dried lake. It’s also the kind of movie where Ed Harris dons blackface, Mickey Rourke plays the president, and Luke Wilson clubs a rock journalist to death with an old blues singer’s guitar. A real “just go with it” kind of film.

As a committed Dylan fan, I bought Masked And Anonymous on DVD as soon as it was available. (The movie only opened in four theaters and rolled out incrementally in select cities over the next several months, so seeing it on the big screen wasn’t easy.) Upon my first viewing, I remember definitely liking it, and I remember definitely not understanding it. Each time I watched it, however, I liked it more. I later championed the movie in 2007 upon the release of another Dylan film, Todd Haynes’ kaleidoscopic I’m Not There, on the grounds that Masked And Anonymous was the “true” oddball Dylan flick.

By the time I screened it (twice!) last week ahead of talking with Larry Charles about the film’s 20th anniversary, it seemed to me like an almost straightforward (and addictively watchable) dystopian comedy. I have a blast every time I see it. My arc with Masked And Anonymous is not unlike my experience hearing many Bob Dylan songs — what initially seems impenetrably dense eventually comes to feel like pop music.

When I told Charles this last week during a Zoom call, he shared a surprising revelation: What I have seen truly is the straightforward version of Masked And Anonymous. The actually bonkers incarnation is the original three-and-a-half-hour cut culled from a sprawling 155-page screenplay that Dylan insisted — against the pleas of the film’s producers — that Charles shoot in its entirety. Only a small number of people have ever seen this version, which Charles describes as a “musical comedy spaghetti western,” and most of them were suits and moneymen who loathed it and demanded that he cut the film down. (This “Larry Charles Cut” of Masked And Anonymous evokes Renaldo And Clara, the nearly four-hour 1978 film that Dylan himself directed and then pulled from circulation. Though unlike that largely improvised film, Masked And Anonymous is entirely scripted.)

In the end, public response was not any better: Masked And Anonymous bombed at the box office and was excoriated by film critics like Roger Ebert, who gave it a half-star out of four and called it “a vanity production beyond all reason.” But that perception has changed somewhat over the years. Hardcore Dylan fanatics like me have embraced the film as a lovably gonzo product of Dylan’s utterly unique imagination. And Charles himself believes in the film now more than ever. “I thought it was an epic, and I still do,” he says. (The Dylan-themed podcast Jokermen, with whom I currently collaborate on a separate Dylan podcast about The Never Ending Tour, are hosting a rare 35mm screening of Masked And Anonymous with Charles in Los Angeles next month.)

As Charles outlined the making of Masked And Anonymous for me, it became clear that what happened off-screen during the shoot was just as bizarre as what happened on. The project began as a proposed comedy series for HBO inspired by Dylan’s love of Jerry Lewis movies, which he binged while on tour in the late ’90s. In the show, Dylan would have portrayed a Buster Keaton-type character who encounters a series of outrageous eccentrics in a post-apocalyptic world. Dylan and Charles were fairly outrageous eccentrics themselves at the time, showing up to the pitch meeting “wearing pajamas” (Charles) and “dressed like a gunfighter — a black cowboy hat, black duster, black boots, black gloves” (Dylan). Nevertheless, HBO bought the pitch, prompting Dylan to immediately bail. (“It’s too slapstick-y,” Dylan claimed, according to Charles.)

Instead, Dylan and Charles spent two years working on the Masked And Anonymous script. Along the way, Jack Nicholson and Johnny Depp briefly showed interest in playing, respectively, the unscrupulous concert promoter Uncle Sweetheart (ultimately played by Goodman) and the loyal roadie Bobby Cupid (the role that went to Luke Wilson). When Depp backed out, he loaned out his personal disc jockey to Dylan, and the DJ set up inside a teepee on the set to pipe songs into an earpiece plugged into Dylan’s ear. Dylan also suggested that all of the characters act out their scenes in dance, even as he struggled to hit his own marks. Charles shot the idea down.

Incredibly, despite this insanity plus a low budget and only 20 days to shoot, Charles was able to finish the film. Two decades on, he fondly recalled the chaotic production and the close working relationship he had with Dylan.

(Warning: This interview includes spoilers, though I would argue this is the kind of film that is still surprising even if you know what happens in advance.)

How did you meet Bob Dylan?

All of these are long stories. I was on a plane with Larry David going back to New York while we were doing Seinfeld. We had a little break, and we decided to fly back to hang out. A guy named Eddie Gorodetsky was on the plane. He was a comedy writer that Larry knew and I sort of knew. He came over to us and started talking, and immediately I could see Larry’s eyes glazing over. He said, “Hey, you guys like music or whatever, why don’t you sit together?” And he got up and changed seats.

Eddie sat down next to me and he had a big box of CDs. And he opens the box and it’s all this Bob Dylan stuff. I’m going, “Oh, you like Bob Dylan?” And he’s like, “Yeah. In fact, my best friend is Bob Dylan’s manager.” And I go, “That’s really weird because I had a cousin when I was a kid who I haven’t seen since I was five years old, who I’ve been told by my family that he’s Bob Dylan’s manager.” And he said, “What’s his name?” “Jeff Rosen.” He’s like, “That’s him.”

So Eddie hooked me up with Jeff, who I hadn’t seen for 30 years, and we became very close. One of the things with Jeff is I never talked about Bob Dylan with him. He’s so inundated with Bob Dylan, that’s his whole life. It’s a lot to carry because Bob is a very, very high-maintenance individual in many ways. He has a lot of projects, a lot of needs. It’s a logistical nightmare.

About two years went by. Jeff called me one day and he went, “Would you be interested in meeting Bob?” And I was like, “Yeah, of course!” He’s like, “He’s interested in doing this comedy idea. He’s been watching these Jerry Lewis movies. Would you just go talk to him about it?” And I was like, “Definitely.”

Bob has a coffee house in Santa Monica that he owns. I don’t know if he still owns it. It’s got a boxing gym in the back. I figured, “I’ll go have one meeting with Bob Dylan. I mean, what’s the chances of anything coming of it? And I will be able to tell all my friends that I met Bob Dylan.” I had no aspirations whatsoever.

I told them I was there and he comes out through the kitchen. The assistant comes over and says, “You guys want something to drink?” And I go, “Yeah, I’ll have an iced coffee.” And Bob says [affecting a Dylanesque voice], “I want something hot. I want a hot beverage.” The assistant goes away, comes back and puts our drinks down, and Bob immediately picks up my drink, my iced coffee, and starts drinking it. So now, right off the bat, I’m like, “What do I do when Bob Dylan’s drinking my drink? Should I say something? I don’t know, fuck it.” After a while he goes, “What’s the matter? Don’t you like your drink?” And I’m like, “Well, you’re actually drinking my drink. You stole my drink.” And he laughed. And we started talking about the idea almost right away from that moment. That’s how the relationship developed.

How did your collaboration work when you were writing the script?

I spent a solid two years in a cubicle with him writing. I mean, he had unending energy. We would write sometimes for 12 hours a day — writing, talking, working things out, not necessarily always scribbling. One of the first things he did was show me this beautiful box he had, and he opened the box and he dumped out all these scrap papers with little notes on them. And he said, “I don’t know what to do with this.” I started looking and there were names of characters: Uncle Sweetheart, Bobby Cupid, Tom Friend. And I said, “Well, these could be characters in a screenplay. And here’s a great line of some kind, an aphoristic line that could be a line of dialogue that’s said by this character.” He’s like, “You could do that?” And it’s like, “Yeah, of course.” I realized that’s how he writes his songs, he just has these scraps and he slowly synthesizes them into this new thing. That’s what we started doing with the screenplay.

My assumption was that Dylan originated the dialogue and you were the story guy.

Well, something about me that’s interesting, I think, is that I’m a great channeler. I sort of became Bob Dylan. So there’s actually a lot of Dylanesque dialogue in the movie that I wrote. But again, it was inspired by and channeled from him.

We had a very equal give and take. The only thing was he would never let me take home any of the scraps. I had to transcribe anything like that and leave the scraps there, because he knew how valuable anything that had his handwriting on it was. We were drawing on all kinds of different sources. We were experimenting, we were cutting and pasting. There was a lot of experimentation that even transcended the ideas to some degree.

One thing that stood out to me during after watching Masked And Anonymous twice this week was how much the movie seems to reflect its time — that awful post-9/11 era in America when the country was involved in two wars and the mood was very jingoistic and reflective of George W. Bush’s fundamentalist Christian allegiances. Do you feel like that informed the movie?

Well for me, in the visual style, that was important. The movie opens with Bob on a bus driving through downtown L.A. and Skid Row. And that underbelly of America was very much a great metaphor for the movie, the Third World America at that time. That’s how I imagine it. But in terms of specific politics, Bob was interested at that time in the Civil War. He was very, very obsessed with the Civil War. And a lot of the lines, which also wound up in Time Out Of Mind and in Love & Theft especially, are very Civil War influenced. So we were juxtaposing these Civil War ideas, which is gallantry and a regal quality to a lot of the language, onto this dystopian, postmodern America and seeing what would happen. A lot of it was, “Let’s try it and see what happens.” That beautiful experimentation is really the inspiration for the movie and it’s what to a large degree propels it.

There’s a lot of show-business satire in the movie, as well as meta commentary on Dylan’s own career, like when Jessica Lange’s character asks, “Are his songs going to be recognizable?” Did that come from Bob?

A lot of the autobiographical stuff — which there was a lot of autobiographical stuff in that movie — came from him. Especially Tom Friend, the Jeff Bridges character, he plays the archetypal music journalist who wants to challenge Bob, and he’s asking about Zappa and Hendrix. That’s all Bob. I think that’s from actual conversations that Bob’s had with journalists over the years where they ask, “What about Hendrix? He always left it hanging out.” Those kind of things are very much Bob.

Killing off the music journalist at the end must have been cathartic for Dylan.

That was a very tough scene to film. We shot the whole movie in 20 days and everybody was on a really, really tight schedule and doing it is essentially because of Bob. And Jeff Bridges literally had to leave the night that he was going to be killed. They had a plane to take him to his next location, which was some bigger budget movie. We’d worked 24 hours. Everybody was really tired. I wanted to make sure nobody got hurt in that kind of situation. But then his death is transcended. He has a beautiful line at the end, Jeff Bridges when he dies, which I can’t quote right now. But all that stuff, it started to dovetail nicely into a stream of consciousness, a feeling that seemed to really work for the movie. It’s very surprising and powerful and emotional in ways that weren’t really to be expected.

One of the strengths of Masked And Anonymous is the amazing cast. How did that come together?

We kept being told before we made it that Jack Nicholson wanted to play Uncle Sweetheart and Johnny Depp was going to play Bobby Cupid, and that was the original twosome. Both of them dropped out very quickly. I think Johnny Depp went to do Pirates Of The Caribbean or something like that. But as soon as Luke Wilson heard that we were doing a movie with Bob, he’s such a Bob freak that he volunteered to be in the movie as anything. And ultimately it was great for him to play Bobby Cupid.

Then the idea of John Goodman doing Uncle Sweetheart came up, which I loved. And then having Jeff Bridges be in the movie with John Goodman, because I was such a Big Lebowski fan, I thought, “Wow, those two guys as antagonists really appeals to me.” I think John really responded to the part, but a lot of the other people responded to just the idea of working with Bob. We were able to attract a lot of people because of that, like Penelope Cruz and Jessica Lange.

There’s also Val Kilmer, who is in one of the film’s best scenes. Was his monologue improvised? It’s very stream of consciousness.

The movie is completely written. But I wanted it to feel like it was spontaneous and made-up, and that people were just spewing this off the top of their heads. I wanted it to feel like improvised Shakespeare in a way. Someone like Val, he just really relished that opportunity. We kept just shooting and shooting and shooting that scene, and he was finding moments.

Val Kilmer, Mickey Rourke, all these people that were supposed to be difficult, they were all just pussycats around Bob. And we wound up loving each other, and I maintained friendships with a lot of people for many years after.

How did you direct Bob Dylan?

[Chuckles.] He had a lot of very interesting ideas about how he wanted to do his performance. He tried a number of accents on me. I was like, “What is this? I don’t think this is right.” One time he wanted the whole movie to be in dance. Everything was going to be a dance. He had called Toni Basil, and I was like, “We don’t have the time to choreograph the entire movie like that.”

On the first day of filming we were going to shoot the first shot, which is Bob at this apocalyptic bus station, and it was a crane shot. I’m on top of the crane, and the crane’s supposed to come down onto him and Laura Harring, who’s playing The Lady In Red. As we’re getting ready to shoot, I’m hearing music in the background and it’s very distracting.

I’m asking people, “Do you hear that music?” Everybody hears it and it’s like, “Where’s that coming from?” People are scrambling around the building, and they’re running outside to see where this music’s coming from.

I see Bob through the monitor and he’s getting antsy and impatient. I’m like, “Man, this is the first shot of the day. I better go down and talk to him.” So I come down off the crane and I walk up to him, and as I’m walking towards him, I’m hearing the music get louder and louder and louder. And I’m like, “He really is a musical genius! He’s emanating music!” And then I realize he’s got a bug in his ear and the music is coming out of this bug in his ear.

And I go, “What are you doing?” And he points to the bug, and he tells me the name of the song — “Memphis, Tennessee” or whatever it was — that he was playing. And I was like, “You can’t do that during the scene.” And he said, “Johnny Depp told me that I should play music during the scene. It’ll help me do the scene.” And I’m like, “Johnny Depp did not tell you that! It’s very distracting. We’re hearing it everywhere. You can’t even hear what you are saying right now because the music is blasting in your ear.”

I find out that he’s hired Johnny Depp’s DJ. Johnny Depp has a traveling DJ who has set up a teepee outside of the parking lot. I go running out to the parking lot and there’s the teepee, which I didn’t notice before. And there’s a guy inside the teepee, very nice guy. And I’m like, “Hey man, you got to cut the music.” It took me 20 years before I finally read that, indeed, for some bizarre reason, Johnny Depp really does play music in his ears while he’s doing his scenes. So these were the different things Bob did to approach his performance.

Bob would be so into what was going on in the scenes. There’s a scene where John Goodman and Jessica Lange are going back and forth and he’s sitting there and he’s got dialogue. But he would get so into their acting that he would forget that he was in the scene. And so he would forget his lines, he’d forget his cues. Also, the idea of blocking, going from point A to point B in the scene, these things were not really natural to him. Jeff Bridges was amazing, he is a consummate filmmaker, which he does not get credit for. He’s been on sets since he’s four years old, and he was very, very generous to Bob and helped walk him through a lot of these things.

But ultimately what we did was I would have Bob’s stand-in walk through the scenes, and basically do the scene with Jeff Bridges or John Goodman or Luke Wilson or Penelope Cruz, whoever it was, and Bob would stand there and he would watch the stand-in do the scene. He would copy the stand-in, and that’s basically how the performance was created.

The first time Dylan appears in the movie, he’s in prison and he’s also wearing a wig. On the DVD commentary track, you mention that Bob started wearing the wig off-camera, too.

Yeah. He did like the idea of wearing the wig so much that when we went to Sundance, he showed up in a wig, but a wig that he bought at CVS or Walgreens. And then I saw that he did a couple of music videos where he was wearing the wig. He did some live shows where he wore the wig. He was digging wearing the wig. If you know Bob and his work like Masked And Anonymous or Renaldo And Clara or the Rolling Thunder era, you know he’s all about masks and makeup and masquerades and layers of identity. So I could see why the wigs appealed to him.

In the studio, Dylan is known for working quickly and not wanting to do a lot of takes. Was he like that on the set as well?

Well, because it was 20 days there was not a lot of time. Everybody was off book, including him. He has this incredible memory. I mean, you see him on stage and he’s reeling off the songs. He doesn’t have a teleprompter or anything. He just knows all his songs by heart, those dense, poetic songs. He knows them and he could just do them, and it was the same with the dialogue. He didn’t really stumble too much on the dialogue. It was more just forgetting his cue or not hitting his mark. But in terms of the dialogue, he was pretty good, and I wanted to keep that spontaneous edge so that we did not do a lot of takes. I wanted to really capture as much as I could in real time.

For the most part Bob Dylan doesn’t say much. A lot of the movie is him looking on stoically while somebody maniacally pontificates at him.

Well, that almost goes back to the original concept for the comedy series, which was him walking through these landscapes, like Buster Keaton or Jacques Tati, and reacting rather than generating anything. Almost like a Candide feeling to it. So he’s not very verbal, but because of that when he is verbal — and there’s a lot of verbiage in the movie — it’s very interesting and profound. And, as I’m sure you feel, there’s some great, incredible lines. Lines that I still quote to this day.

Absolutely. Also, his line readings are often quite musical. I love the scene where Dylan is on the bus with Giovanni Ribisi, And he talks about his dreams. “I dream I’m walking through fire … intense heat.“ I’m a big fan of how he says intense heat.

[Laughs.] That’s one of my favorites. I thought he gave a very laconic performance. Again, it has this spaghetti western kind of feeling to it. It was a very kind of Clint Eastwood performance to me, and I really liked it a lot. Of course, people are going to complain. He was going through a period there where people were really bitching about him a lot about all kinds of things. but I found this performance to be very enigmatic and interesting and very much in keeping with the spirit of the movie. Anything else would’ve been false. As stylized as this movie is, we were trying to achieve a level of honesty, too.

In the “making of” documentary included on the DVD, you said that you filmed Dylan performing 22 songs with his band, though only about a half-dozen or so ended up in the released film.

Yes. There’s 22 songs. In the three-and-a-half hour version, they may all be in there, as a matter of fact. This was one of the first movies that was shot digitally. And I said, “Look man, I want the camera just rolling all the time.” So we shot all the rehearsals. And then there were things like “Dixie,” that was done just to warm the band up. He did a lot of covers of songs, and so I wanted to make sure all that stuff got captured.

I don’t know where those songs are now. Jeff has all that material. I have the three-and-a-half-hour cut, but I don’t have all the footage. All the dailies and all that stuff.

Do you remember any of the songs he played that didn’t make the movie?

I know that he played a lot of R&B stuff, like “Mona.” And quite a few of his own songs that were from the album that had just come out, which I think was Love & Theft. There was a wide, wide range of covers, from the Allman Brothers to “Dixie.” His band was so great and so versatile and so responsive to him that they could almost launch into anything. But the specifics of which songs didn’t make it, I would have to go and check for myself. I’m not even sure anymore.

On the commentary track you mention he played “If You See Her, Say Hello.”

Right. When we started to winnow down that movie from the three-and-a-half-hour version to the two-hour version, a lot of that stuff just fell by the wayside. And they’re great performances. That band, that was one of his motivations for even doing the movie. He loved that band so much he wanted to capture them at that peak moment in their existence.

What was Bob like on the set? Did he keep himself at a distance from the other cast members?

On the first day, I went into his trailer and said, “Look Bob, we have 20 days to shoot the movie. All these people are here for you. So what I would like to propose is I’ll put a chair on set, a comfortable chair for you, and you should sit on that chair. And between setups, instead of going back to your trailer, sit on that chair so the people, when they’re walking by you, they can just go, ‘Hi, Bob.’ It’ll mean the world to people to be able to just say hello to you, and maybe you’ll say hello back. But whatever you do, they’ll each have that encounter with you and it’s going to inspire them because we have a lot of work to do in a very short amount of time. And that connection to you, which is why they’re here, will just be a life-changing experience for them.” Because he’s a reticent person. He’s not a particularly social person and he’s not really into that kind of stuff.

And he was like, “Okay.” And he did it. So he was very personable. He happens to have a great sense of humor. It’s very dry, but he was very personable to people and he had a pretty good time, actually.

How did Bob feel about the movie when he saw it?

Well, one of the first things he told me was, “I’m never going to see this movie.” [Laughs.] And I understand that in a way. I don’t really look at my stuff after I’m done either. It’s like, don’t look back. That’s his attitude, and I appreciate that because you can’t really do that much about it. Supposedly 20 years later he did watch it, and I was told off the record that he loved it. So that’s as much as I know about that. But he told me right off the bat, “The people will like this movie if they get a chance to see it, but the critics are probably going to hate it.” And he was completely right about all that stuff.

How did you process the film’s reception? Did Bob’s prophetic words comfort you at all?

Well, it was my first movie and I thought it was great. I really was very proud of it. I thought it was an epic, and I still do. So I honestly was shattered by the response. I mean, now I can laugh about it, but I saw my life going in a certain direction based on that movie and instead I had no movie career whatsoever. It died right there. That was it. I didn’t make another movie for quite a few years, and so I was devastated by the response and was really super profoundly disappointed.

Roger Ebert was particularly vicious toward the movie.

I’ll tell you a quick story. The Sundance people, they loved the movie. They decided they would make it the centerpiece premiere at the Sundance Film Festival that year, which was a very prestigious slot at a very prestigious film festival. I was really excited, and all the actors came to the Sundance Festival to be there for the premiere. And Bob came wearing that wig.

Roger Ebert, he was like the dean of the Sundance Festival. He had this special seat in the centerpiece theater and he was treated like a king. He was royalty there. And he came backstage and he wanted to go around and have pictures taken with all the cast because it was a very starry cast. Val was there, and Mickey Rourke and Luke and John and Jessica and Penelope, all those people were there.

So we’re backstage, he’s taking pictures, he’s happy as could be, and finally it’s time to take a picture with Bob. And I go, “Okay, let me go ask Bob if he’s willing to take a picture.” And I go over to Bob and I go, “Hey, Roger Ebert’s over there, and he just wants to take a quick picture with you.” And he’s like, “I don’t feel like taking a picture.” And I’m like, “Okay.” And I go back to Roger and I go, “Hey, Bob’s not really in the mood to take the picture, blah, blah.” And he gets really, really pissed off. He storms out, takes a seat, watches the movie, and then trashes the movie the next day in his review. So that was the kind of thing that I had no control over that may have affected the whole course of the movie.

Over the years, what have you heard from Dylan fans about the movie?

Well, there’s two streams, really. One is the people who’ve discovered the movie subsequently and love it. There’s nobody I’ve met who’s actually seen the movie who doesn’t think it’s a mind-blowing movie. So I’m very, very pleased with the response it’s had. Look, we’re talking about it 20 years later, so I know it’s had an impact on an audience. And that audience is around the world, by the way, because I get asked about it in all these different countries that I’m in and there’s always an interest in it.

So there’s that group. But there’s an equally large group that has no idea that the movie exists. And I’m always shocked by that. I’ll be working on something and I’ll go, “Well, you know, I made this Bob Dylan movie.” And they go, “Bob Dylan movie? What Bob Dylan movie?” They’ve never even heard of it or knew that it existed. And then I try to turn those people onto it, of course.

Do you still have ambitions to release the long “Larry Charles Cut” of Masked And Anonymous?

Oh my goodness. I have been trying to get it released lo these many years. I have been haranguing Jeff and anybody else I could talk to about it. We’ve seen over the last few years all of these Bootleg Series box sets coming out with different cuts and alternate takes, and maybe that’s what they are going to plan on doing at some point. I hope they do it soon. But I only, literally, have a VHS copy of it. Jeff and Bob’s company have all the reels, all the dailies. Everything is in a vault somewhere. Part of the problem, of course, is that the initial release did not do well. I think if the shorter version had been wildly successful, there would be more interest in this longer version.

In the DVD “making of” documentary, you said making this film was a transformative experience for you.

It really was. Not just the shooting of the movie, but the writing of the movie, and just being with Bob Dylan every day for a couple of years, and being able to pick his brain and hear him think and laugh with him. He really was like an inadvertent guru to me. It wasn’t like he set out to share wisdom, but he was just spewing wisdom through his very being, and I was lucky enough to be exposed to that.

The failure of the movie really forced me to decide what’s important, because he taught me about trusting my instincts, and I really did follow that path. And I’m really much more satisfied, I think, as a person and as an artist because I have done that.

As painful as the film’s initial failure was for you, it also seems appropriate, given how many Bob Dylan albums were poorly received in the moment and then hailed as classics in retrospect.

I think that’s exactly true. The thing about him is he’s had public humiliation, he’s had failure, he’s had it all and he’s still here. That’s one of his greatest lessons. He was like, “It really doesn’t matter, you just have to keep doing it.” And he’s very unpretentious about that aspect of it.