The Byrds are on the shortlist of great American bands. Between 1965 and 1973, the L.A.-based group released 12 albums — including classics like Mr. Tambourine Man, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, and Sweetheart Of The Rodeo — that profoundly influenced the future direction of California rock, country, and psychedelic music. Among the members are singer-songwriters who went on to have important careers outside of the band, including Gram Parsons, Gene Clark, and David Crosby.

The one constant in The Byrds was Roger McGuinn, a founding member and the only person to appear on every record. It’s him playing the 12-string guitar parts that grace iconic singles like “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and “My Back Pages,” which subsequently informed pop-minded experimental guitar bands from multiple generations, from the Velvet Underground to R.E.M. to Wilco, as well as heartland rockers like Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers. “I regard The Byrds as a nine-year detour from my dream of being a folk singer like Pete Seeger,” he says during a recent interview. “But we wanted to be like The Beatles, and we got to do that.”

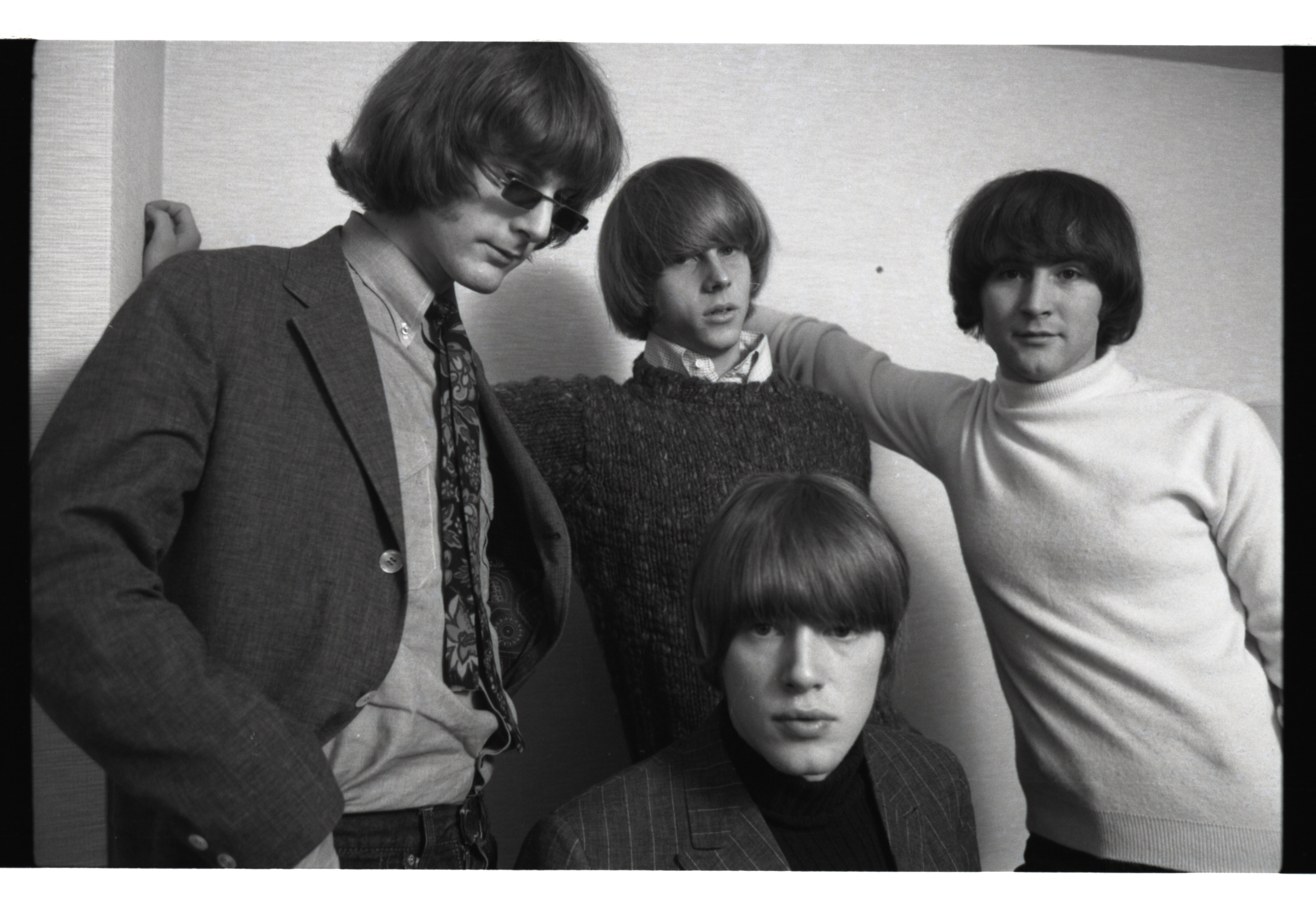

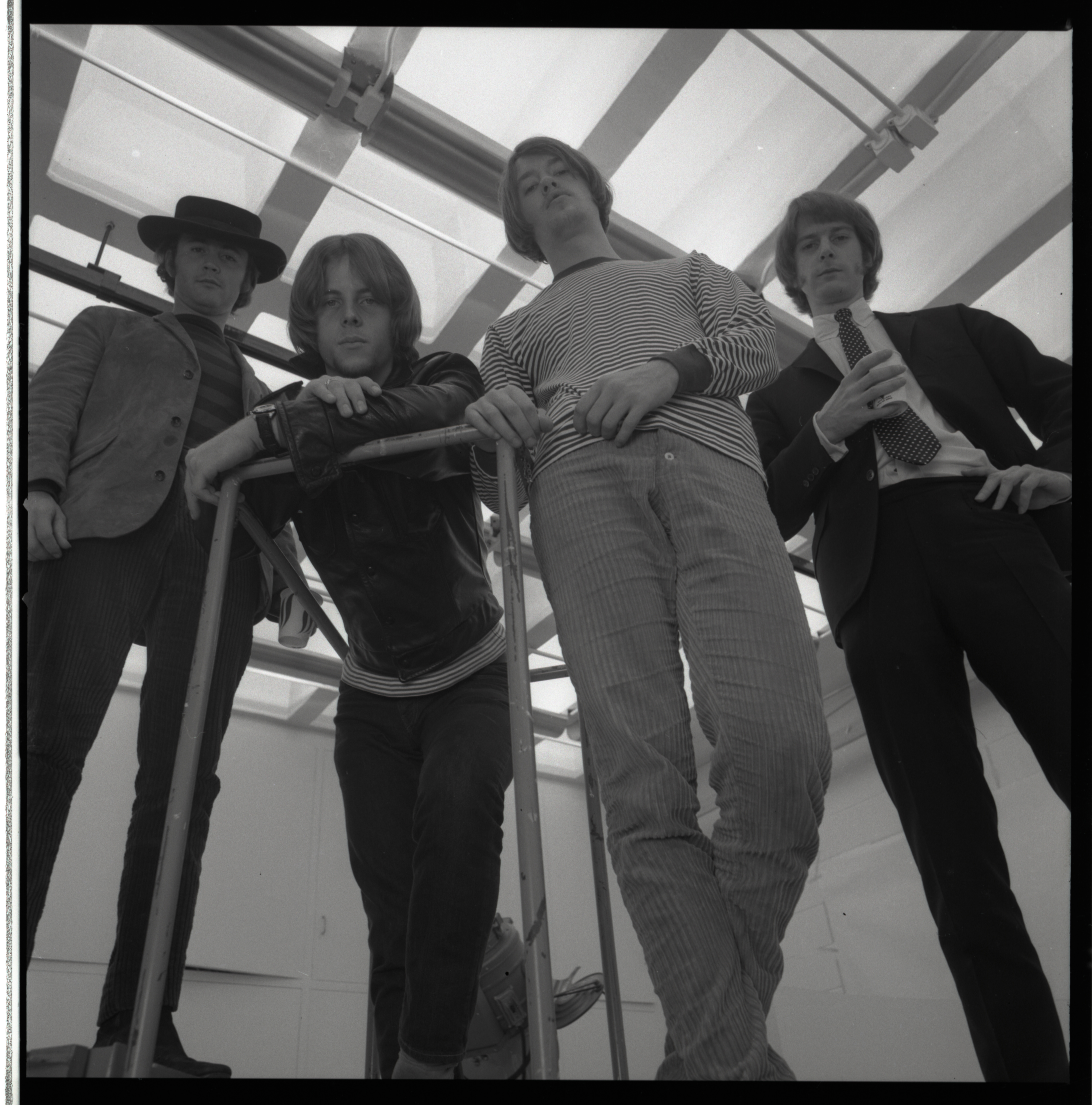

Along with fellow surviving members Crosby and Chris Hillman, McGuinn contributes to a forthcoming collectible art book about the band, The Byrds 1964-67, due out September 20. When we spoke, he had recently celebrated his 80th birthday. But he remains a sharp and spry musician, as evidenced by how often he slipped into Byrds songs on his trademark 12-string during our Zoom call. He also can easily recall details about the most pivotal albums, and his (not always favorable) impressions of his former bandmates.

Here are McGuinn’s thoughts on eight classic Byrds albums.

Mr. Tambourine Man (1965)

I was a go-to studio guy in New York for 12-string acoustic folk records. I played on Judy Collins’ third album. I was the musical director on that. And I recorded the demo of “The Sound Of Silence” for Paul Simon. I did a lot of stuff for Elektra Records. I was one of their guys. I asked F.C. Hall, who owned the Rickenbacker company, why he just decided to make an electric 12-string guitar. And he said, “I did it for the folk scene.” And I said, “But folk singers don’t play electric guitars.” Maybe it was a prophetic thing.

We had to get a hit single before we could do the album. So, it wasn’t an album deal we got from Columbia. They were very conservative back then. They had Doris Day and Steve Lawrence & Eydie Gormé, and some jazz and classical stuff. They were a little bit scared of rock ‘n’ roll. They thought it was like the mafia doing heroin. [Laughs.] So, the deal they gave us was for one single. And if we got a hit with the single, you could go back in the studio and record the album. So, that’s what happened. In January of ’65 we recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man,” with the help of the Wrecking Crew and me on my Rickenbacker electric 12. And then Gene Clark and David Crosby and I went into the studio and recorded the vocals for it. And then it sat around between January and May.

In the meantime, I knew Dino Valenti from San Francisco, who was later in Quicksilver Messenger Service. Dino wanted to start a band with space helmets and wireless microphones, and that sounded really cool to me. So, I almost left The Byrds and went off with Dino to do that, because Columbia wasn’t releasing the single. We were sitting around for four or five months. Finally, they released it and it shot up to number one. And then we got to go back into the studio and record the rest of the album.

When you recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man,” the Dylan version hadn’t been released yet?

We got a really rough demo. He was going to put it out, but Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was singing on it and he was a little intoxicated. Crosby said, “I don’t like it, man. That’s 2/4 time, it’s not rock ‘n’ roll. It’s not going to play on the radio.” It was four and a half minutes long and they wouldn’t play anything over two and a half minutes. So, I rearranged it with a little Bach kind of stuff on the front and the back, cut it down to one verse for time, and it was a hit.

We had a lot of Dylan’s stuff on there. Some of our own things. “We’ll Meet Again” was kind of a gag. I always wanted to put a gag song at the end of a record. It was sort of a reach out to Stanley Kubrick, who had done Dr. Strangelove. “We’ll Meet Again” was in the movie.

Turn! Turn! Turn! (1965)

There was a tremendous amount of pressure. It was overwhelming. I mean, the whole scene, recording in the studio. I was scared to death of the Neumann Telefunken microphones that cost $5,000. It’s like, “Oh, we got to be careful around here!” It was a very intimidating experience.

The Wrecking Crew played on the single “Mr. Tambourine Man” and the flip side, “I Knew I’d Want You.” But The Byrds got to play on the whole album of Turn! Turn! Turn! The reason they used the Wrecking Crew… well, [producer] Terry Melcher knew that we weren’t really a real band. I mean, Michael Clarke never learned how to play the drums at that point. And these guys saved a lot of money. I mean, sessions were expensive. So, we knocked out “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “I Knew I’d Want You” in one three-hour session. And it took 77 takes to get “Turn! Turn! Turn!” with the real Byrds. I think it was the feel, the rhythm track. I mean, the Wrecking Crew had a bond. They were like fish and they kind of swam around together. The Byrds didn’t know how to do that yet. It was a brand new band. And it took a long time to figure it out. Now, Michael Clarke did become a good drummer eventually. By the time he got to Firefall, he was a really good drummer.

I had worked on Judy Collins’ third album as musical director, and she did “Turn! Turn! Turn!” And I was also a big fan of Pete Seeger’s version. I went to all his concerts at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and wherever I could find him. And he did that song in 1959. I also worked with The Limeliters in 1960, they also did that song, but they called it “Everything There’s a Season.” And they did it a real kind of folk-y way. They didn’t put a beat to it. I put the rock ‘n’ roll beat to it, and I think that made a difference.

Gene Clark was the main songwriter. He and I started the band. We started writing songs together when I was doing a solo gig at the Troubadour, and he came backstage and nobody was liking what I was doing. I was doing folk and rock, and folk people were kind of snobs about rock at that point. But Gene wasn’t. He liked the Beatles and he said, “Let’s write some songs and see what happens.” So, he and I started writing songs and then Crosby came along, but Gene continued writing songs. He was very prolific. I wasn’t really that interested in writing songs all the time, but he was. And it paid off for him. “Set You Free This Time” is a wonderful song.

Fifth Dimension (1966)

We were number one on the charts, and then The Beatles wanted to meet us and we hung out with them and The Rolling Stones and went on tour with The Stones. And we were hanging out with Bob Dylan. I remember one night Bob Dylan, Phil Spector and I were at the Troubadour and we were backstage. And Phil Spector turned to me and said, “You know what? You’re in with the in-crowd.” I mean, it was exactly what we were shooting for. We got there and held it for a couple of years.

I would say the defining factor of Fifth Dimension would be the “Eight Miles High” track. We were influenced by Coltrane and Ravi Shankar. I had a Phillips tape recorder, a cassette recorder — it was a new invention and I’d recorded Ravi Shankar on one side of a tape and John Coltrane on the other. And we would just flip that tape over and over. That was the only music we listened to for a month. So, it got kind of steeped in our heads. It was a recurring theme on that album. Now, it was way ahead of its time for rock ‘n’ roll. People misinterpreted it as being psychedelic. They thought we were stoned, which we were, but … [Laughs.] We didn’t intend it to be psychedelic. In my opinion, it was an emulation of John Coltrane, a respected jazz musician. I was trying to do jazz. And I did, but nobody got it.

When I heard Coltrane, it was like a burning fire through my chest. I mean, wow! It really affected me. I listened to what he was doing, and he was emulating sounds of Indian music with his saxophone. And it’s just amazing stuff. I got to see him play live in Chicago. That was cool. But that was my intention, to expand my territory and play different kinds of music instead of just “three chords and an attitude” rock ‘n’ roll. But it was misunderstood. And just having the word “high” in it, and the fact that we were kind of counter-culture guys, got it banned on the radio, which wasn’t good.

I like to experiment with different things. Like The Beatles, when they first started out they were doing three-chord songs. And then they got into the studio and realized that the studio is an instrument, too. I remember I found an old record player that was thrown away. It was in a garbage can. I pulled it out and I got the amplifier out of it, and I put it into a cigar box and I put a little three-inch speaker that I’d gotten from a walkie-talkie in the cigar box and drilled some holes and set it up with batteries and put a jack on it so I could plug into it. And it sustained like crazy. I used that on “Why,” on the flip side of “Eight Miles High.” It was before the Pignose amps and all those things.

Younger Than Yesterday (1967)

“So You Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” came from Chris Hillman and I hanging out at his house, and thumbing through one of those team magazines with different rock bands on the cover. We were kind of amused by the one-hit wonders. They’d be there one week and you’d never see him again. And we thought it would be fun to write a song about that. Millard Thomas, who played for Miriam Makeba, he had that guitar lick. And I showed it to Chris and he liked it. And so, the song started to come together. [Plays the riff to “So You Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star.”] We got Hugh Masekela to play on it. Again, we were doing jazz.

“Have You Seen Her Face,” that’s one of Chris’ early songs. Really great. And he bloomed. He hadn’t been writing songs before that. “CTA-102,” that was my friend, Bob Hippert, a science guy. He read about Cambridge, they found a quasar and it was making a radio signal. It sounded like intelligent signal from outer space. And we got excited about that. And then it turned out just to be an anomaly. “Renaissance Fair,” Crosby and I wrote that together. Man, that was a good song. “Time Between,” another Chris Hillman song. “Everybody’s Been Burned,” one of David’s opuses. And then there’s “My Back Pages.” That came about because Jim Dickson, who had been The Byrds manager, pulled up alongside me in traffic in L.A. And I rolled down the window and he said, “Hey, you guys ought to do ‘My Back Pages.'” So, I went home and got the record out and it sounded something like [sings the opening lines of “My Back Pages”]. And I went, “That’s not going to play on the radio.” So I put a little lick to it. And then the breakout. And it worked. It was a hit.

The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1968)

I had a Moog synthesizer. I saw it at the Monterey Pop Festival. There was a guy named Paul Beaver that had a little tent with one of those things in it and he was demonstrating it. I was like, “Wow, what a great instrument. And I want to get one.” So I bought one, it was like $9,000 back then. And I recorded [the unreleased song] “Moog Raga” and some other stuff with it. It didn’t have a sequencer, so it didn’t have a real precise time signature that you can do with modern synths. You can just set up a beat with them. But this one, I just had to do it manually, like hitting the keyboard, but I played the whole thing myself.

We were trying to expand our territory. When we first came out, they said, “Folk rock.” We didn’t want to be just folk rock. So, we started doing country and we started doing jazz and we started doing other things and we just wanted to stretch it. I did have an idea to do an album that represented the history of music — not just American music, but world music. When it started with early music and the Gregorian chants, and going through the Renaissance, and then getting into the blues and jazz and rock ‘n’ roll and country music, and then running it out into space with a synthesizer. I didn’t get anybody to go along with me on it. It was just too ambitious of a project. And we ended up doing Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, which I’m not ashamed of at all. I think we did a nice job with that.

“Draft Morning” was kind of theatrical. We had sound effects and we were obviously not in favor of the Vietnam War, as most of our generation was not. And so we wanted to say something about it. We weren’t a real political band, except for a couple of songs. But “Draft Morning” was a definite anti-war song. “Turn! Turn! Turn!” was, too: “A time for peace, I swear it’s not too late.” So, we didn’t really go full-out political, like Joan Baez, and go to jail for the cause and all that. But we were political and we did say some things. And I love “Draft Morning.” I thought it was a really good little mind movie about somebody getting drafted and going to war.

Is it true that David Crosby left the band before this album because you wouldn’t put his ménage à trois song, “Triad,” on Younger Than Yesterday?

No, that’s not true. That’s just a cover story for his attitude. He was upset because Terry Melcher didn’t like David and wouldn’t put any of the songs on the album. And subsequent producers were like that. I remember Alan Stanton used to keep me after school at the studio saying, “What’s wrong with David Crosby?” It’s like, “Why can’t we work with this guy?”

No, David was angry that we didn’t use his song as opposed to “Goin’ Back” or the other Goffin and King song, “Wasn’t Born To Follow,” which are great songs.

Was your relationship with Crosby always fraught?

It started out very friendly. We were buddies. We hung out together. Took acid together. The “trying to get your songs on the record” part was what the contention was. And Terry Melcher liked me, and so did the other producers. I didn’t write that many songs, but I was getting them on the album. And David was having a problem.

There’s an urban legend that the horse on the cover of The Notorious Byrd Brothers is meant to represent Crosby. Is that true?

No. It was just a photo session. We were out with some horses and we went into this cabin that had four windows and I think Michael brought his horse inside the cabin. I was always kidding, “Well, if we wanted to make the horse look like David, we would’ve turned it around.”

Sweetheart Of The Rodeo (1968)

Gram [Parsons] had a trust fund and he was a rich kid. We didn’t know that when we first met him, but Chris Hillman ran into him in a bank in Beverly Hills. I guess he was getting his monthly allowance. It was after David Crosby had left The Byrds. Chris Hillman and Kevin Kelley, his cousin, and I were The Byrds, and it was not working on stage because there was no rhythm. I was playing lead, Chris was playing bass, and Kevin was playing drums. We needed somebody to fill in for Crosby. So, Chris ran into Gram at a bank in Beverly Hills and invited him over to the rehearsal studio where we were working out. I was still into the “Eight Miles High” thing. I asked Gram if he could play some McCoy Tyner-kind of piano. And he sat down and played a little Floyd Kramer-style piano, country piano. I’m like, “Well, he knows how to play the piano. He’s got talent. We can work with him.” And he turned into George Jones in the sequin suit right after that.

Country music was another aspect of folk music. It was kind of slicked up folk music. So, it was not foreign to me at all. We had done Porter Wagoner’s “Satisfied Mind” earlier on, on the Turn! Turn! Turn! album. So, we were dabbling in country, but it wasn’t until Gram came along that we decided to go to Nashville and record the Sweetheart album. Gram was just so in love with country music, it was infectious. He’d play us these songs and there’s so much emotion and so much storytelling. We just fell in love with it.

It wasn’t a stretch to go to Nashville and record. It was fun. We had a great time doing it. We played poker at the Ramada Inn in the daytime, went to the studio at night, and we’d drink beer and smoke pot. It was like a party. And we had these great studio guys, like Lloyd Green on the steel guitar. It was the real A-team studio guys in Nashville. And they loved it. They had never had a session that was so unstructured, because to them, they put out their lead sheets and would play exactly what was written on the page and that was it. And we said, “Do whatever you want, man. Come in when you want and stay as long as you want.” Gram recorded Sweetheart with us. And then it turned out that he was signed to another label and they threatened to sue us. So we had to replace some of his vocals, but then later they came out [on the 1990 box set The Byrds].

The only blowback we got was when we did the Grand Ole Opry. We got out there and we started doing “You Ain’t Going Nowhere,” which was fine. And then we were supposed to play “Sing Me Back Home.” And Gram said, “My grandma’s listened to the Grand Ole Opry all her life. I want to do a song I wrote for her.” And then he went into “Hickory Wind” and that got us in trouble with everybody. The audience was a little standoffish, because we had… it wasn’t real long hair. It was not like it is now.

Gram was out of the band soon after that, right?

What happened was I was in the Chad Mitchell Trio [in the early ’60s], and we toured with Miriam Makeba in the South. And it was a very hostile environment because we were four white guys with a Black woman in a car and they’d call us names and everything. And I apologized for America. She said, “You ought see my country. If you ever get a chance, go to South Africa.” So, later I got an offer to play South Africa and I went, “Well, okay.” And they offered some money and so on.

We flew over to England and we were going to fly from London down to Johannesburg. But in the meantime, we met The Rolling Stones and they took us out to Stonehenge. And Keith Richards and Gram hit it off as buddies. And Keith said, “You can’t go to South Africa. It’s against the union rules. You’ll be banned from the musicians’ union. So, Gram, of course, who wanted to hang out with The Rolling Stones, quit The Byrds. And we flew down to South Africa. It was a disaster. It was just horrible. We got death threats. We didn’t play for mixed audiences like they had promised, except in Zimbabwe. We had a mixed audience in an outdoor venue. But the rest of it was all indoor concerts and I got the flu. And then we didn’t get paid.

Did you see Gram after that? Was the split amicable?

Yeah. I forgave him. He and Chris got together and started The Flying Burrito Brothers, and I would hang out with them. They had a house in the Valley and I went over there. And I was just blown away by all the great songs they were writing together. Gram and I played pool and we rode motorcycles together, like a bunch of hillbillies or something.

The Ballad Of Easy Rider (1969)

Peter Fonda flew to New York with Easy Rider and screened it for Dylan in the city. Dylan wrote down some notes on a cocktail napkin that was in the screening room. And it said, “The river flows, it flows to the sea / wherever that river goes, that’s where I want to be / flow river flow.” And I think there was a chorus, too. But it was incomplete and it didn’t have a melody. So, Peter got back on a plane in New York, flew over to my house, and he came to me with this napkin and he presented to me like, “Bob, wants you to have this, man.” I went, “Cool.”

I looked at it and it had those lyrics and I got my guitar out and made up a [sings open of “The Ballad Of Easy Rider”]. So, I finished it off and we called it “The Ballad of Easy Rider.” And it did real well. A few weeks later, Bob called me up and said, “Take my credit off.” He didn’t want a credit on it.

The album was a hit. It sold a lot of copies and generated some income, but the band was, at that point, doing kind of watered down material. We had “The Ballad Of Easy Rider” on the record, but the rest of the record was kind of irregular and didn’t really have Byrds hits.

I wanted ask about the song “Jesus Is Just Alright,” which was a relatively recent gospel song when you guys did it. Were you already a Christian when you recorded that? Was there an evangelical aspect of putting that on the record?

Well, I’d been raised in Catholic schools. And then I delved into Eastern religions in the early ’60s and got out of that. I was drifting along without any specific religious attachments. Gene Parsons brought up the song “Jesus Is Just Alright,” which was from the Art Reynolds Singers. It’s really a good track. But it wasn’t from a religious perspective, it was more just a really cool song.

Clarence White was a real standout in this era of the band.

He was excellent. Jimi Hendrix would come backstage and go over to Clarence and shake his hand. He was the best guitar player I ever worked with, and I’ve worked with some good guys. But yeah, Clarence was a genius. He was brilliant. He had figured out how to do flat-picking like Doc Watson. He could do the bluegrass stuff. And he incorporated that into his electric guitar style. And then he and Gene Parsons developed that B-bender that would raise and lower the B string on a steel guitar, and that gave it a whole other sound. Clarence was a really sweet guy. He was my friend. We hung out together a lot.

The Byrds (1973)

I considered The Byrds a good brand name, like Coca-Cola, that you wanted to keep going. I was willing to persevere up until ’73, when Crosby came over to my house with Elliot Roberts and said, “Some of the songs you guys are doing are pretty good, but some of them aren’t.” And I had to agree with him, because I was letting all the guys have their own songs on the records. And some of them were not up to the same level as we had been.

Crosby got David Geffin to go along with doing a Byrds reunion album with the original Byrds. And I said, “Okay, we’ll do that. And if it works, we’ll go on tour with it. If it doesn’t, we’ll hang it up.” Crosby and I agreed that I would hang up The Byrds that I’d been touring with and just stop that. If it wasn’t the original Byrds, then it wasn’t going to be The Byrds.

And the album wasn’t bad. It wasn’t great. It wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t a reason to continue with the name of The Byrds. It was more of a party than a recording session. And Crosby was in charge. He was the big man on campus after CSN had made some hits. He provided us with entertainment — a lot of pot. And we were stoned the whole time. So, we had a nice time, but it’s not a great record. I think the best parts were some of the Neil Young songs that Gene Clark did. I got a couple of songs on there, but they weren’t really as well done as they could have been. The wrong key, maybe too high vocally, so on. It was okay. I don’t know what it did sales-wise. I never noticed it chart reading, but it was all right.