I.

The pilgrims’ voyage on the Mayflower was a disaster. The self-proclaimed religious refugees hired a bad crew and had little-to-no luck on their way to Virginia. High winds and choppy seas, low supplies, months-long delays, and damage to the boat’s main beams all led to a terrible Atlantic crossing for the 130-odd people on board. By November 11th, they couldn’t take any more and anchored in Cape Cod — far north of their intended destination, the Virginia Colony.

The land they arrived at had recently been ravaged by an imported disease that killed off 90 percent of the local population. The desperate English settlers robbed graves and food stores to sustain themselves. They stayed on their ship through that first winter and severe cold temperatures and constant hunger took its toll. By the time spring rolled around only 53 of the original passengers were left alive.

By March of 1621 the English disembarked and began living in the empty houses of the decimated local village. It wasn’t a great start.

The English luck turned around when they met a Patuxet man named Squanto — who’d already experienced a lifetime’s worth of war, slavery, and worldwide adventure. Squanto and what was left of the Wampanoag bonded with the English. They traded supplies for food and taught the English the best ways to fish the bay and farm the land. By the time harvest season rolled around in autumn, things were looking up for everyone. The Wampanoag had people to work with after their European disease-fueled apocalypse, and the English pilgrims had a real settlement.

Sometime around the end of September, the pilgrims decided they were in good enough shape to host a harvest festival with their newly bonded friends and saviors. Harvest festivals, or Thanksgivings, were common practice already amongst the Spanish, French, and Virginia colonists, so the Plymouth event wasn’t anything new. It took the self-mythologizing American spirit to make it worthy of a holiday.

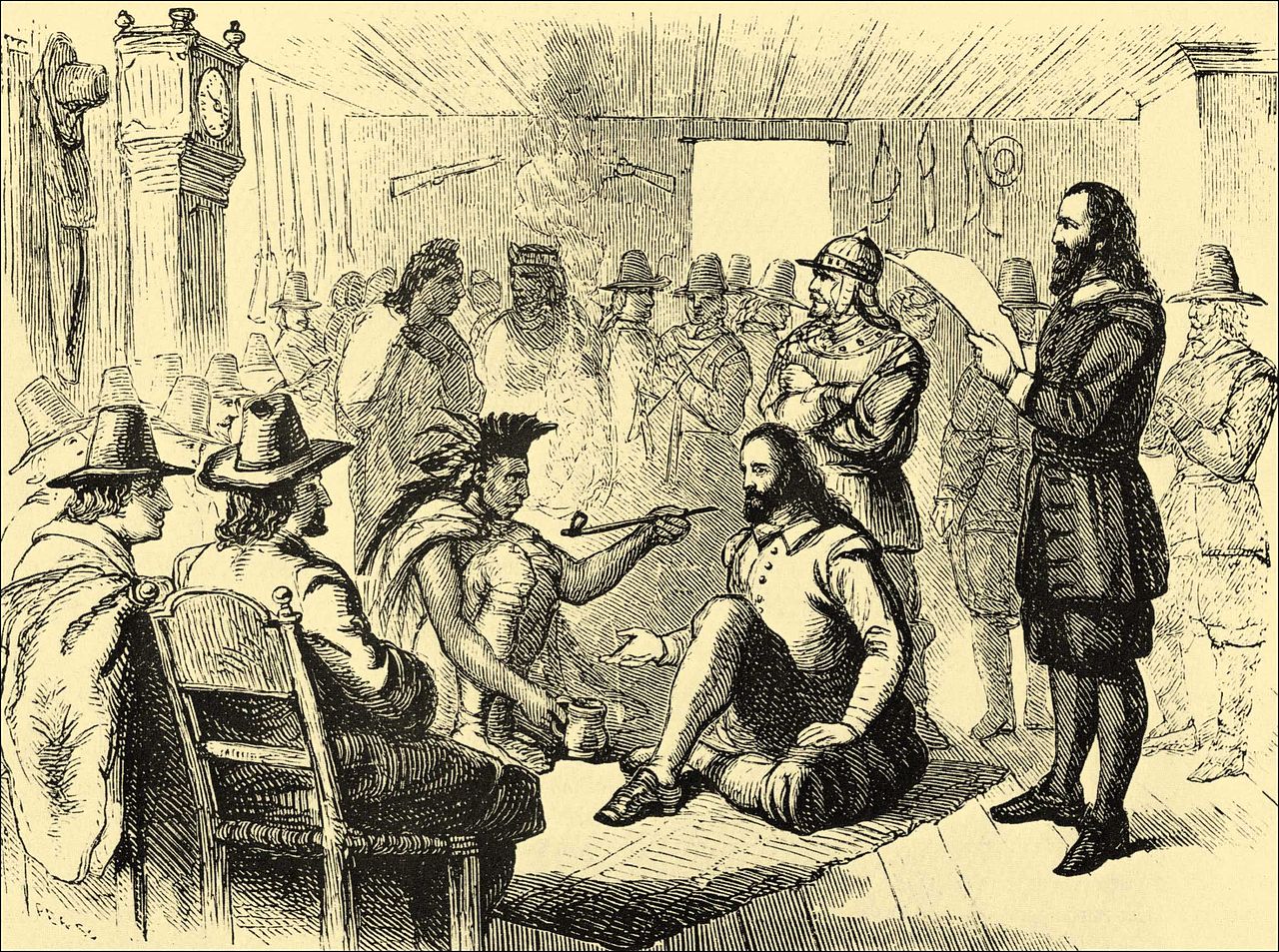

The 50 remaining English and about 90 Wampanoag gathered for a three day feast, to celebrate the bounty of their collective labor. The meal included wildfowl, shellfish, cod, corn, squash and pumpkin, and five whole deer. The Wampanoag and English had toiled side by side throughout the year, and this was the fruit of that union. They gathered around bonfires, hearths, and tables to celebrate what they’d accomplished together as a diversified unit of people fighting to survive in an uncertain world.

II.

The first ten years of my life I lived in a hippy town at the end of the road, off the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state. My identity was never really anything I thought about. I was a boy who watched Transformers and G.I. Joe, just like the neighbors. I went fishing with my dad in the Straits of Juan de Fuca and hunting with my family in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains. Being Indian was never anything I thought about more than to wonder whether I’d ever grow my hair long, like all the warriors I saw in the history books.

Then my dad got a promotion to run a new grocery store in another town in Washington. In 1989, we moved from a very blue county to a very red county in the southern reaches of the state. We traded the Straits of Juan de Fuca for the muddy banks of the Columbia River; from a town that had farmer’s markets and art festivals to a town that didn’t even have a library (outside of the public school). My first week of school was when I first became an “Indian.” Some older white kids encircled me and then body slammed me into the grass while doing a “war dance” around me. Then they all took turns spitting on me before walking away.

My infraction? Refusing to do the pledge of allegiance at the beginning of the day. I made the mistake of telling them as an Indian that we don’t do that.

Over the next three years, I’d try and hide the bruises and bloody lips I’d get on the playground, while groups of white kids gathered around, beat me, and yelled racial epithets. “Dirty Indian.” “Prairie Nigger.” “Salmon Fucker.” The school administration’s solution was usually to put me in detention or Saturday school. The message was clear: I was the problem. Eventually, I gave in. I started fighting kids, throwing the first punch. I figured “if they’re going to blame me for everything, I might as well land a few shots.”

When I wasn’t brawling I retreated into myself. I’d been playing the piano since I was five years old. So I dove deeper into that art. I also started cooking. I’d often watch The Great Chefs on PBS after school, and one day I tried to recreate a recipe I saw on some particularly inspiring episode. It was a bit of a disaster, but I was hooked. Cooking and piano became my dual forms of therapy. I could lose myself in the notes of Rachmaninoff and the flavors of a well made bolognese.

Eventually, things came to a head. A group of boys had been ambushing me after gym class and the principal’s solution was to suggest that we box in the basement of the high school gym. When my parents realized that I had no choice but to keep fighting or spend my life running, they pulled me out of school. I spent the last few years of my education being homeschooled (not the religious kind), playing piano, and cooking every single day.

As I grew older, I delved into the world and history of Indigenous Americans. My dad took me to powwows all over the western USA. I felt a connection to a people who shared my violent and hate-filled history. I grew my hair long and braided it like a good Indian. My parents relocated to another blue county in Washington and life moved on. Until ’92.

Being a “long-haired Indian” attracted attention. Over the course of about one month, I was stopped by the local police ten times. Every time it was the same “Where ya goin’ boy?” “The reservation’s back that way, redskin!” The pat downs and ID checks became routine. I asked my dad about it. His response was always the same, “We’re Indians, that means we live in a police state. Don’t ever forget that. You have to just do what they say, keep your mouth shut. It’s not worth gambling your life.” My dad had spent two-years collectively in jails around America for what we call “walking down the street Indian.”

I cut my hair when I was 14. I was never harassed by the cops again.

I graduated high school when I was 16 and saw two paths in front of me. I was either going to the CIA in New York to study cuisine and become a chef, or I was going to a music school to become a concert pianist. The choice was hard. Food preparation had become a coping mechanism in my life. It was my therapist, my escape, and was slowly becoming part of my identity. Conversely, I could go onto any stage across Washington State, slay some Chopin, and feel like I had a sense of worth that wasn’t attached to my race.

I chose the third way. After a year in music school, I bailed. I transferred to the American University in Washington, DC, and started pursuing a degree in Political Science. My goal was to become an FBI agent and work on Indian Reservations. I wanted to help my people. I was 17 and idealistic. The world I found on the quads of American University in the late ’90s was just as hate-filled and demeaning as what I’d grown up with. People would yell across a party for me to make them a canoe or ask where my wigwam was.

I needed new escapes and found alcohol, cocaine, mushrooms, weed, and sex. When those didn’t work, I decided to go back to what I knew best. I found a job working at a restaurant.

III.

The Wampanoag and the English pilgrims of Plymouth carried on as allies and friends well into the 1630s. However, by that time the Puritans and the Dutch had arrived, the Puritan’s fundamentalist view of Christianity had no room for the Plymouth English (who were Anglicans separatists, but also down with Indian ways) or the Wampanoag (who they referred to as “godless savages”).

The Puritans and Dutch started flooding the colony in waves of migration, eventually pushing out the Plymouth Pilgrims for not being extremist enough. They soon started to expand beyond the Connecticut River, forcing the tatters of the various local indigenous populations into resource conflicts, all sides scrambling to hold onto the little they had left. The Pequot War would be the first major massacre and retaliation between white settlers and the indigenous population. It set the stage for every massacre and war to come over the course of American history to the present day.

Between 1640 and 1675, the Puritans took land and slaughtered Indians. This was a stark contrast to the Plymouth Pilgrims — who literally paid for their land and sought cooperation with the locals. But, alas, the fundamentalist extremism of the Puritans and the capitalistic drive of the Dutch won out, and they pillaged and plundered what was now being called New England (even their fellow Pilgrims). There are very easy parallels one can draw between the Puritan extremist Christian, who used terror and thievery to create a state in the New World, and the tactics of other extremist groups like ISIS. They stole what they wanted and killed anyone who asked questions, including their own.

Make no mistake, it was these radicals who set the tone for the rest of America’s history, especially when it came to dealing with the indigenous population.

By the 1770s, the English descendants of the Puritans were ready to throw off the yoke of British taxation. A group of white land-owning elitists gathered to form a new government in Philadelphia and declare their independent intentions. In their long fight towards independence, they drafted a declaration — enshrining these words forever: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare, is undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

These words tainted the United States’ view of the indigenous peoples of the Americas indefinitely. It also serves as a reminder that the famous document exalting the notion that “all men are created equal,” doubled as a piece of racially-profiling propaganda.

The continued destruction of the Indian way of life so that white Europeans could expand ever westward continued during the Revolutionary War. While the eastern theater was concerned with fighting the British, the western theater was a more covert war, focused on the destruction of as many indigenous communities and people as possible.

In 1777, the Continental Congress appointed Thanksgiving holidays and prayers for the first time. They strove to enshrine that very first moment when the Plymouth Pilgrims and Wampanoag joined forces and fought together against the elements and world to survive together with a day of prayer — remember, still Puritans.

Two years later General Washington carried on that Puritan-defining quality and launched the Sullivan expedition with these orders:

The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.

I would recommend, that some post in the center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provisions whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.

But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them.

The Iroquois were destroyed. At least 40 cities and towns were scorched to ash. The surviving members of the Six Tribes had to flee into Canada to survive the slaughter and looming ravages of winter. The Iroquois renamed George Washington Conotocarious — which literally translates to “devourer of towns.”

In 1789, Congress was in the midst of ratifying our constitution. On September 25th of that year, Congressman Elias Boudinot from New Jersey petitioned the house and senate to have now-President Washington declare a national day of thanksgiving and prayer. On October 3rd, 1789, President Washington enshrined November 26th at the first official Thanksgiving Day. According to President Washington’s decree the holiday was “to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed, to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shown kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord.”

At the same time, September 25th, 1789, to be exact, the second amendment to the constitution was submitted. It’s hard to ponder the meaning of this amendment by today’s standards (God knows, we try). We’ve all grown up in a nation that goes from sea to shining sea with all those amber waves of grain in between. However, for the colonialist who had just beat one of the biggest kids on the international block, their entire focus was west. Manifest Destiny was their goal, and every single American needed a gun to fight those “merciless savages” who stood in the way of forward progress (echoes of fire hoses in Standing Rock). The right of all Americans to bear arms and form well-regulated militias was also about legally forming irregular armies and arming civilians, who could constitutionally slaughter any Indian they saw

As Thomas Jefferson put it, “Nothing will reduce those wretches so soon as pushing the war into the heart of their country. But I would not stop there. I would never cease pursuing them while one of them remained on this side of the Mississippi.”

IV.

I worked hard in that kitchen in Washington, DC. It was what I’d been told over and over again that America was supposed to be about. Everyone was on a level playing field. Guatemalan dishwashers worked alongside second-generation Mexican line cooks, blue-collar white sous chefs, Korean bussers, middle-class college student servers, and so on. Everyone was the same there. Food served as the great unifier and equalizer.

I eventually left America for good in 2003. I needed a fresh start and wanted to know what else the world had to offer; I was tired of living in a country with two histories. One that used mythology to build an identity, and one that saw those same heroes exposed as monsters. I bounced around Prague and Moscow. I went around the world several times. I became an adventurer and war zone traveler, looking for experiences that would ambush my system, the same way walking home from school had as a kid. I was broken and looking for anything that might glue me back together.

Over the years, I came back to cooking and started working as a chef. But it never quite felt right. I always saw food as a self-help tool, not an occupation. As my film and writing career started to develop, food once again became my escape. I look forward to the break in the day when I get to cook my family dinner. I can turn off my brain and focus on the construction of something that will nourish and bring joy to whoever we’re eating with. Food, I have found, literally breaks down every barrier (from within and without). Cooking a great dish makes me feel good. It brings people together around a table. It feels real. And that’s why I love Thanksgiving.

I took me years to understand what the holiday was about. For most of my childhood and early adulthood, standing for the national anthem, or pledging allegiance, or celebrating any American government holiday was just not something we did. There was, and still is, too much pain and suffering associated with being an Indian in America to bend a knee to that flag and those heroes. But Thanksgiving is different. Thanksgiving was about two groups people who were near total annihilation, then came together. They thrived against all odds. Together.

All the devastation that came after is the guilt of another aggressor, an America who has always lived in a post-truth world from day one. An America where institutionalized racism and hate never had to be normalized because it has always been the norm.

I’ve railed against the Eddie Bernays of the American capitalistic experience before. And it was these same marketing men who decided that the modern Thanksgiving meal would be a set menu of turkey, stuffing, yams, green beans, black olives, mashed potatoes and gravy, and so forth. Basically, this was to upsell those products during an early winter sales slump. The only real item in that menu that the Pilgrims and Wampanoag actually ate was maybe the turkey. Otherwise, it’s just all Don Draper-bullshit.

This year, as I wrestled with how far we’ve come and how far there is to go, I’ll be sorting my Thanksgiving menu by looking at what the Pilgrims and Wampanoag likely ate.

I’ve mapped out a four-course menu. We’ll start with oysters lightly poached in black truffles and butter then topped with rum macerated blackberries, candied shiitake mushrooms, and chives. I love this dish. The oysters are ever so slightly poached with the black truffle giving them a briny and earthy note. The candied shiitakes add an edge of sweetness and earthiness to match the truffle in the butter. The blackberries (macerated with rum, star anise, cardamom, and allspice) give a jolt of tartness and acidity that cuts through the brine and umami; kind of like a fruity caviar.

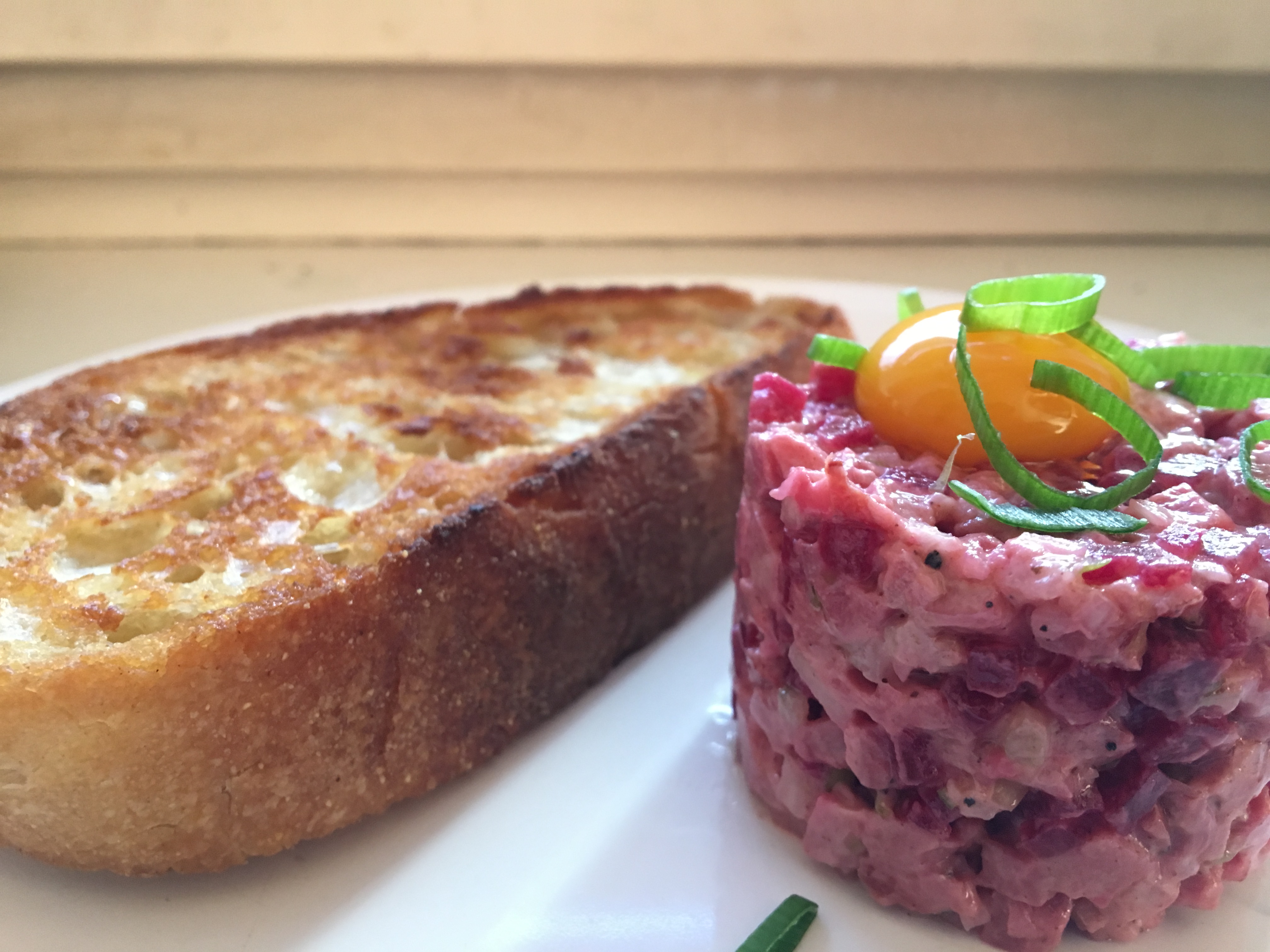

Next, will come smoked duck breast and roasted beet tartare with dijon mustard, fennel, green onion, apple cider vinegar, and topped with a quail yolk and grilled bread. I imagine there was a lot of smoke at that first feast, so a nice piece of cold-smoked duck breast minced with a slow-roasted winter beet will bring those cured-earth flavors together. I’ll balance it with the sharpness of the fennel and dijon. The quail yolk mixed in gives a velvet texture to the whole affair.

After that, I’ll serve a corn pajeon filled with mussels, bay shrimp, scallops, ginger, and green onion — topped with red beet sprouts and a side of wild berry ketchup for dipping.

Pajeon aren’t new world, but assuredly there were corn pancakes at that first meal back in 1621. These ones are delightfully satisfying with the beet sprouts linking the last dish to this one ever so slightly. The medley of seafood reminds the diner that the fruit of the sea was crucial to those early Pilgrim’s survival, and corn was a cornerstone of every meal. The wild berry ketchup (closer to what ketchup was back then) brings an intense umami and tartness at the same time to balance the starch and brine of the pancake.

The main course will be a seared venison loin in a port and cranberry demi-glace served with citrouille anna. The Wampanoag brought five whole deer for the feast, so venison is a must-have on any authentic Thanksgiving menu.

I grew up eating venison every year, so this one comes naturally. I seared off the loin in a skillet with sage, marjoram, and garlic cloves with plenty of butter. While it rests, I added in about a cup of good port and about a dozen halved cranberries to deglaze the skillet and make the demi-glace. The pumpkins are a made in the pommes anna style — by layering pumpkin and clarified butter in a pan and slow-roasting it until it’s a buttery stack of deliciousness that adds a light starch to the protein and tart demi.

All of that will be washed down with a cinnamon-infused rum old fashioned, because holidays are for drinking. It’s not an exact menu that would have appeared at that Thanksgiving between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag. But it’s something that’s inspired by those people and the foods they had on their tables.

Too many of us are looking to this Thanksgiving with dread. The political process seems to have failed many of us who thought we were on a path towards a more progressive and inclusive America. I don’t know if that’s possible in a country where an entire group of people is subjugated to third-class citizenship status while being trapped in a bizarre form of corrupted communism. Do you really get to be shocked about how racist America is when the reservation-system seems so broken? When we’ve been given back portions of our land but can’t keep a pipeline from being built on it?

And yet… I have no intention of fighting with family or friends over politics this year. I’m just going to cook some good food and invite friends and family to my table. There will be people there from Iran, Israel, England, America, Holland, and Germany. We’ll talk about the events of the year, share what we are thankful for, and look forward to 2017. It’ll be a good group. And, let’s face it, if an Iranian and Israeli can get along at my table, you can probably get along at yours.

This year, more than ever, it’s time for all of us to take a page from the Pilgrims and Wampanoag and work together with those we don’t understand so that by next Thanksgiving we can all sit around a table together and celebrate our survival. Just as they did all the way back in 1621.